Giovanni Pasquali, Research Associate, Global Development Institute, Shane Godfrey, University of Cape Town

The Covid-19 pandemic is having major implications for the resilience of apparel global value chains (GVCs).

State-driven measures to enforce social distancing have led to the downsizing and even closure of supplying firms, especially in developing countries where government support for manufacturers is limited. This dynamic has been worsened by the actions of international brands and retailers which, in a number of cases, have delayed or cancelled orders, and have refused to pay for ongoing production and shipments.

Whilst increasing attention is paid to the implications of Covid-19 for firms in the global South supplying retailers in Europe and the US, we know less about the impact of Covid-19 on regional value chains connecting buyers and suppliers in developing countries. Given that South-South trade overtook North-South trade in the last decade, this is a significant oversight.

As part of the Shifting South research project, we’ve looked at what is happening in Eswatini (formally known as Swaziland), which has been the largest African manufacturer and exporter of apparel to the region since 2014. Our evidence suggests a very different dynamic compared to the North-South value chains that have recently made the headlines.

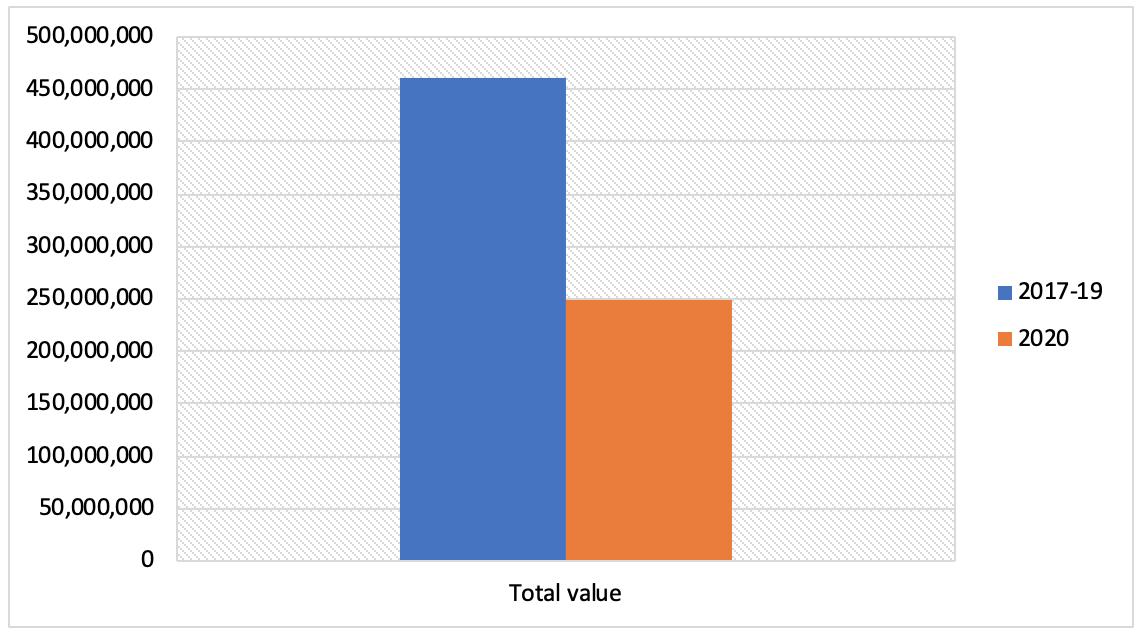

Like many others, the country has been hit hard, with a partial lockdown in effect for six weeks from 27 March. In the March–April period, Eswatini lost 45% of its income from apparel export, with the number of transactions dropping by 26%.

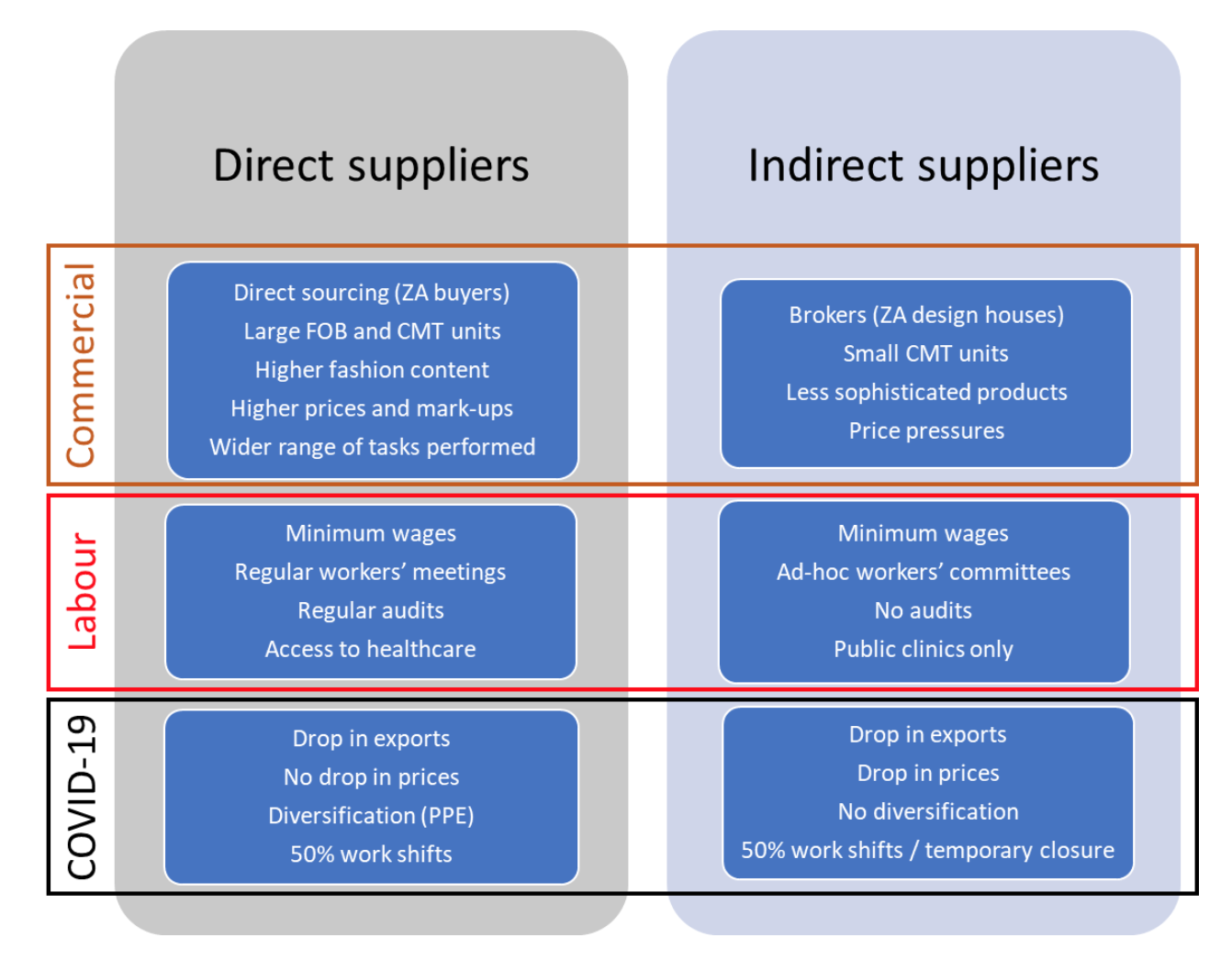

Within the sector, our data suggests that there is significant differences in impact between the larger ‘direct’ suppliers (8 firms) and the smaller ‘indirect’ suppliers (12 firms). The first are characterised by direct contracts with lead retailers in South Africa; whilst the second operate through indirect purchasing via intermediaries known as design houses, which manage the interaction with retailers. As we argue, the differential implications of the Covid-19 pandemic for these two groups of suppliers are further rooted in different commercial and labour dynamics that characterised them before Covid-19 struck (Figure 2).

Following the Covid-19 lockdown, direct suppliers have differentiated their products significantly more than indirect suppliers, with at least four starting to produce PPE for the domestic and export markets. As reported by one manager: ‘We got an opportunity to get into producing PPE and face masks and that allowed us to keep working first for the local market and recently also for export to South Africa, as our main buyer won a tender with the government there. This allowed us to keep paying our workers…’

The Covid-19 lockdown has severely impacted Eswatini’s apparel workforce. As of June 2020, three relatively small indirect suppliers (which employed about 1000 employees) have not resumed operations since the beginning of the lockdown in March, and it is possible that these firms will close permanently. Most of the other plants appear to be operating at about 50% capacity with the labour force split in half and working on rolling shifts (daily, weekly, and fortnightly). Workers are paid only for the time they work, so their income is currently about half of what they were earning at the start of 2020.

Whilst the whole sector is suffering, indirect suppliers are more exposed as they undergo significant price pressures from design houses. Data from the Eswatini Revenue Authority suggests that indirect suppliers have reduced their prices by 14% compared to the 2017-2019 moving average for the same period. Conversely, despite reducing the size of their orders, South African retailers (with one notable exception) have honoured their contracts with direct suppliers and prices have remained stable.

In at least three cases, direct suppliers noted that retailers have provided them with some forms of financial assistance. As stressed by the owner of one manufacturing plant: ‘They assisted me with 80% payment for the staff while I was shut down. They are also supporting me now by commissioning masks for South Africa’. Similarly, the manager of another direct supplier stressed: ‘Fabric supplies are two weeks longer than before and customers’ selling performance is not stable yet. Our main buyer gave us a loan of 5 million ZAR to buy fabrics.’

This evidence sets the Eswatini case apart from Bangladesh, where European and US lead retailers cancelled over 70% of their orders and refused to honour their contractual obligations, leading to the shutdown of factories within weeks of the beginning of the crisis. We therefore provide concrete evidence that cautions against any immediate association between South-South value chains and relatively lower labour standards, further questioning the ‘the falsity of the assumption that the global North has all the solutions to tackle global challenges’.

Despite this evidence, however, the situation in the Eswatini apparel sector remains critical. We’re calling for concerted forms of public, private, and social governance through the simultaneous involvement of firms (including both buyers and suppliers), state, and the sector’s main trade union (until now excluded from consultations) to produce an effective response to the crisis caused by the pandemic.

This research has been conducted as part of the ESRC-GCRF funded project ‘Shifting South: decent work in regional value chains and South-South trade’, in cooperation with the Eswatini Revenue Authority (SRA).

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole