Isis Barei-Guyot, PhD researcher, Global Development Institute

Influencing development

The connection between celebrities and development may not be immediately apparent, but celebrity philanthropism has come to occupy an increasingly accepted role in the field of international development. For example, it is well known that Angelina Jolie was granted the status of Special Envoy for the United Nations. Events such as Band Aid and Comic Relief have normalised celebrities being the platform through which we become aware of humanitarian issues around the world. The media is an effective way to bring the suffering we cannot see or may not have experienced to our attention, and the increasing use of the word “influencer” to describe celebrities who use social media as a platform highlights the power celebrities and the media have to shape people’s behaviour, attitudes and choices, including when it comes to issues of development.

Molly-Mae Hague, who gained celebrity status by appearing on reality television, recently commented on poverty while participating in a podcast, using the now-infamous phrase that “we all have the same 24 hours in the day” to chase economic success. These comments received considerable backlash, and Molly-Mae has now issued an apology. However, before we move on from this incident, we should take a moment to recognise that there are multiple ways in which poverty can be defined and understood and that while celebrities can provide platforms for awareness and have access to valuable resources for change, being a celebrity often goes hand in hand with a neoliberal capitalist system that encourages inequality.

Residual vs relational poverty

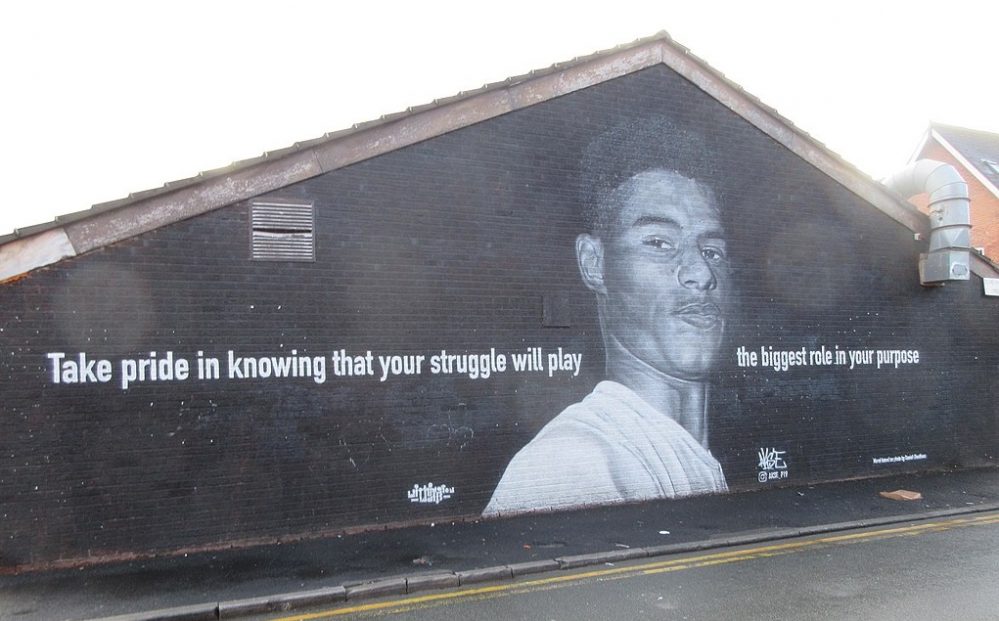

Molly-Mae’s use of her celebrity status to address poverty has been contrasted to the work of those such as Marcus Rashford, a footballer who has been awarded an MBE for his campaigning to tackle child food poverty in the UK. Both of these people are celebrities, both have chosen to use their platform to address poverty, yet their approaches are very different. It is, therefore, important to be aware of the various ways in which poverty can be understood, and Molly-Mae and Marcus provide useful examples for doing this.

The different understandings of poverty can be broken into two main approaches: residual and relational.

The residual approach to understanding poverty is distinctly in line with the principles of neoliberal capitalism, with poverty being understood as resulting from exclusion from capitalist processes. An example of this exclusion is not being able to participate in the market because you do not have formal employment. What is key to understanding the residual approach to poverty is that it locates the causes of this exclusion within the characteristics of the people experiencing poverty, such as irresponsible behaviour or laziness.

In the UK, this approach has gained dominance through widespread neoliberal discourse, creating stereotypes by drawing lines between negative personal characteristics and those experiencing poverty. For example, in the UK, the word ‘chav’ is a stereotype used to assign anti-social behaviour to a whole class of people. It has been so normalised that a ‘challenge’ recently emerged on TikTok in which people use caricature to mock Britain’s working-class for other’s entertainment. This denigration of those who have low-income or are in receipt of social welfare justifies the neoliberal agenda to reduce support from the government to an absolute last resort.

Like the causes, the solutions to poverty are therefore also located within those experiencing poverty from the residual approach- if people work harder, it will contribute to economic growth, which is seen as the primary way to combat poverty. Molly-Mae Hague demonstrated this residual approach to understanding poverty: saying people just need to try harder is the same as saying they were not trying hard enough.

So how does this differ from a relational approach to understanding poverty?

Those who understand poverty from a relational perspective see poverty as a result of the structures and processes associated with capitalist development. Rather than focusing on only the economic aspects of poverty, such as a person’s income, which is characteristic of the residual approach, poverty is understood to have multiple dimensions from a relational perspective. These other dimensions include the human, social, and political.

Experiencing poverty is, therefore, not just about how much money or assets you have. As the above example of the ‘chav’ highlights, the stereotyping and stigma surrounding poverty impacts how others perceive and treat you, and this can ultimately influence the opportunities available to you. Physical and mental health issues are also both a cause and consequence of poverty, with connections being drawn between child poverty and lasting trauma, considerations which are often absent from residual understandings of poverty that paint millions of people as lazy or irresponsible with a broad brush.

By providing space for concepts such as structural disadvantage, the relational approach also recognises that a person can be integrated into the capitalist system and still experience poverty, and therefore calls for neoliberal capitalism to be held accountable for the inequality it produces. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Marcus Rashford campaigned for increased support to be provided to those experiencing food poverty, demonstrating a relational approach to poverty in which it is assumed that poverty is not a choice but an inevitable result of structural inequality, taking the responsibility out of the hands of those experiencing poverty and placing it into the hands of those who are indirectly benefitting from it.

Using your influence wisely

Outlining these two approaches to understanding poverty hopefully clarifies why two people can use the same platform to raise awareness about poverty in such different ways. There has been speculation that this difference has resulted from the different socio-economic backgrounds of the two celebrities, which highlights that, to a certain extent, we cannot expect those with no experience of poverty to be critical of the residual approach that has the support of the goliath that is neoliberal capitalism. Accordingly, we should value the knowledge and perspectives of those who have experienced poverty. It is, therefore, critical to educate ourselves on the different ways of understanding poverty in order to engage critically and compassionately with those who may be struggling to see beyond the boundaries of their privilege.

Top image: Mural of Manchester United footballer Marcus Rashford MBE on Moorfield Street, Withington. Image source.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.