Nana Agyeman, MSc. Development Economics and Policy, Global Development Institute

Much of the conversation around debt in Africa has been about its growing size, while very little attention has been paid to the terms and conditions under which African countries borrow. The devil they say is in the details, so it is critical that we understand both sides of the crippling debt story.

Transparency

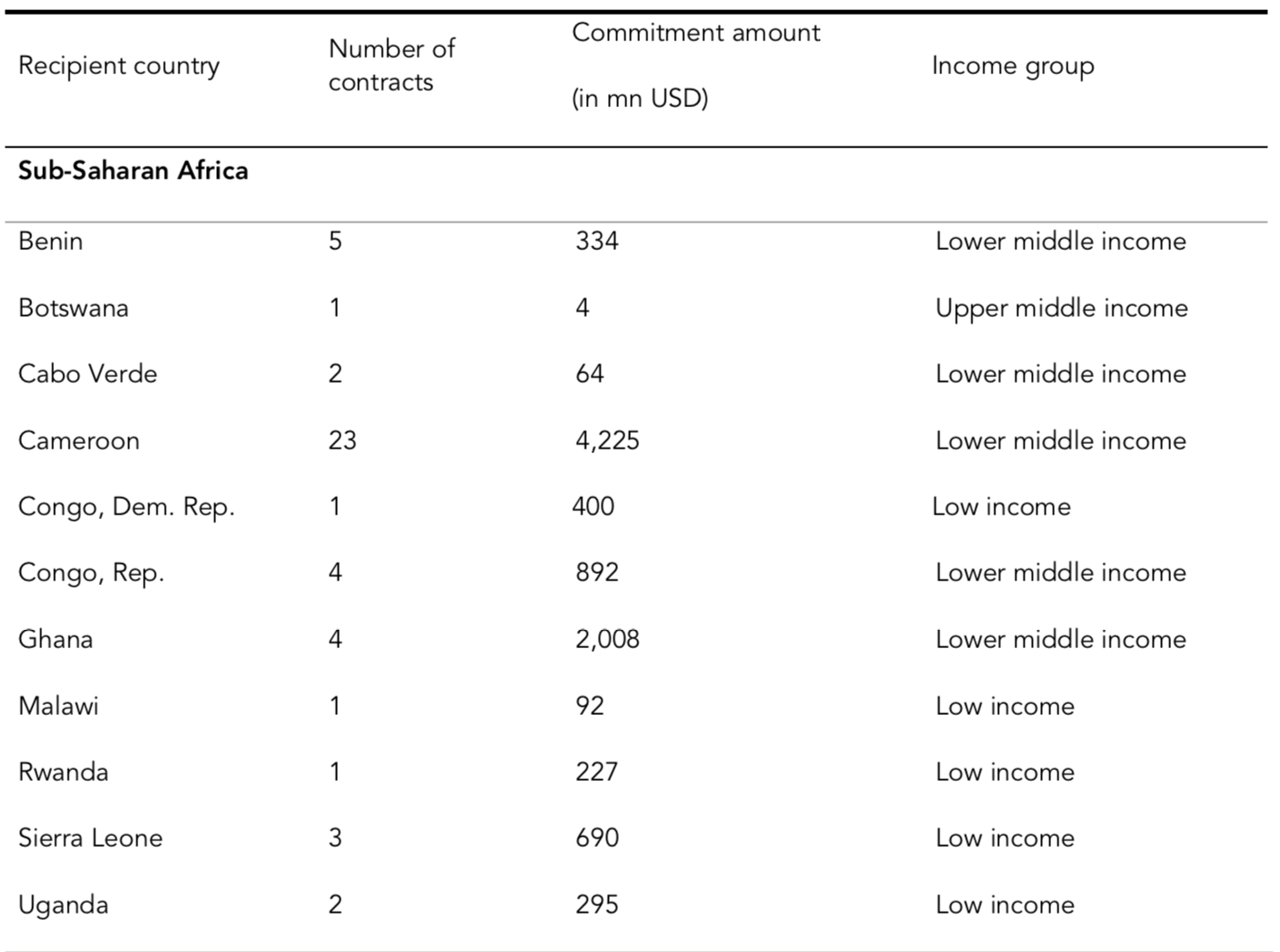

A recent publication by AidData offered readers the rare opportunity of discovering the intricacies of China’s model for lending to developing nations. The researchers focused on Chinese loans to 24 developing nations, 11 of them being from the African continent (see figure 1 below). China remains tight-lipped about its dealings with other countries and that has always been a point of contention between China and the Western world.

With very little transparency on the nature of the loans given to developing countries, accountability is swept under the carpet on the side of China and the borrowing government. African countries are not debtors to China alone so there is reasonable cause for other creditors to be concerned about the nature of China’s dealings with Africa. Without transparency, the true state of affairs and the creditworthiness of a borrower cannot be impartially determined. The report by AidData uncovered some terms and conditions which might indicate why China is able to lavish Africa with loans.

Confidentiality Clause

“The Borrower shall keep all the terms, conditions and the standard of fees hereunder or in connection with this Agreement strictly confidential. Without the prior written consent of the Lender, the Borrower shall not disclose any information hereunder or in connection with this Agreement to any third party unless required by applicable law.”

This is the clause issued by the China Eximbank in all its contracts with borrowing countries post 2014. Similar clauses can be found in all China Development Bank (CBD) contracts as well. This limits debtors in their engagement with stakeholders and might lead to falsely drawn conclusions about a country’s state of affairs. The citizenry who are actively involved in the public discourse may also be missing out on critical information of how their government borrows. However, it must be noted that confidentiality clauses are not unique to China alone. There are other lenders who have similar clauses in debt contracts but are not as extensive as the Chinese. The phrase “unless required by applicable law” is a grey area which is most likely defined by what the Chinese lenders would consider as applicable law or otherwise.

Collateral ties

It is safe to say the Chinese do not leave the negotiation table without a clear plan and commitment from borrowers on how to pay back loans. This is guaranteed by the agreement to create special accounts with banks at the discretion of the lender, which informally acts as a safety net for the Chinese in case there are any risks of default.

As a condition, these accounts are regularly funded with proceeds from projects either associated or unrelated to the main project(s) for which the loan was sought for. The $2 billion deal Ghana signed with China which would apportion 5% of Ghana’s bauxite reserves to China, in exchange for transportation infrastructure projects, is a typical example of how revenue from projects unrelated to the purpose of the loans given can be used as collateral. This further explains the reluctance of the Ghanaian government to discontinue mining activities in the Atewa Forest.

We have seen calls from environmental activists and Twitter campaigns with the various hashtags- #SaveAtewaForest, #SaveAtewa4Water, #AtewaForest bringing to light the potential impact of mining activities on the unique biodiversity of the Atewa forest and the pollution of water bodies which serve as a source of drinking water for 5 million Ghanaians. Global companies who ordinarily would have been Ghana’s customers for bauxite have also joined the conversation, making public statements of their opposition to mining in the area. Again, it must be noted that this type of debt contract provision is not only used by the Chinese but it is not as common in bilateral and multilateral lending between developing nations and sovereign lenders.

The Paris Club Clause Exclusion

“The Borrower hereby represents, warrants and undertakes that its obligations and liabilities under this Agreement are independent and separate from those stated in agreements with other creditors (official creditors, Paris Club creditors, or other creditors), and the Borrower shall not seek from the Lender any kind of comparable terms and conditions which are stated or might be stated in agreements with other creditors”.

This is the only clause that is unique to how China lends to developing nations and there is an interesting reason why. The Paris Club refers to a group of official creditors who work together to provide debt contract conditions to their debtors who may be faced with a crisis and default risks. Paris Club members are guided by the principle of debt treatment comparability to ensure there is fairness in how lenders share the burden of risk. This simply means, for example, if both Brazil and Canada have given loans to Zambia and there happens to be a risk of default, the Paris Club conditions guarantee that Brazil’s debt contract with Zambia does not receive preferential treatment compared to that of Canada’s and vice versa.

Another aspect of Paris Club’s role is the provision of debt relief to debtors, in the form of rescheduling payment of loans and reduction in debt-service obligations. It becomes a more complex issue when we also note that the Paris Club condition of debt treatment comparability further applies to debt contracts between their debtors and other non-Paris Club members, something that does not sit well with the Chinese lenders. In the report by AidData, it was noted that 74% of Chinese lenders do not adhere to this principle.

Cross-Default and Cross-Cancellation Clause

Simply put, the cross-default clause means that for example, if Nigeria defaults under its debt contract with Party A, any other creditor to Nigeria, say Party B, has the right to terminate and demand full principal and accrued interest payable. The cross-default clause is a standard clause common in all commercial debt contracts, so it is not only used by Chinese lenders.

However, other variations of the cross-default clause used by Chinese lenders allow them to terminate and demand payment if there are any risks to other investment interests of any “PRC (People’s Republic of China) entity” in the borrowing country, where “PRC entity” is broadly defined. This tends to put borrowing countries under extra pressure to succumb to Chinese conditions. According to the AidData report, it also appears that the CDB uses loans as a tool for policy influence in debtor countries. This is particularly dangerous because it reduces the debtor’s autonomy in making independent decisions without external influence.

The cross-cancellation clause ties the provision of a loan for a particular project to the successful delivery of other projects linked to the lender. The CDB in the past has triggered this clause to shield itself when it dealt with Argentina, on the basis that there was some opposition to a pre-agreed $4.7 billion syndicated loan from Chinese banks to build two hydroelectric dams, due to environmental concerns raised. Per the clause, China was going to pull out of a $2 billion CDB loan for a railway project in Argentina but needless to say, there was a quick turnaround from the Argentine government. Connecting this to the case of Ghana, it appears that if there are any cross-cancellation clauses in Ghana’s debt contracts with Chinese lenders, mining in the Atewa Forest is likely to go ahead no matter the pressure from various stakeholders.

Conclusion

All indications reveal that China, like every other country, seeks to protect its interests first. There are variations in how different countries and institutions lend to Africa, but it is up to Africa to make the best of its debt negotiations and more importantly, the loans received. There is a pressing need to continue to advocate for further transparency from governments and public scrutiny of debt contracts signed with lenders.

Civil society organizations in Africa have a major role to play in raising awareness of debt contract analysis, to allow necessary pressure on governments to do right by the books. However, this is not a silver bullet to the challenge of receiving unfavorable terms and conditions from lenders. No country has altruistic intent while it negotiates with other countries since we are all eager to bargain for the best deal. African leaders must find their leverage points and do better.

- Nana studied for an MSc in Development Economics and Policy at GDI. Find out more about our master’s courses.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.