By Virgi Sari, PhD researcher at The Global Development Institute

Following the vote to leave its natural trade partner, the EU, the British government is now faced with the challenging task of designing its new trade policies, including those with developing countries. The leading role of the UK in shaping global development through trade with developing countries is long established. As Brexit moves forward, the important question becomes: how will the UK maintain its legacy of using trade to contribute toward global development? How to construct new trade policy that is development friendly?

The Principles

On 26th October 2016, Professor Alan Winters of the University of Sussex delivered a lecture as part of the Global Development Institute Lecture Series on “Post-Brexit trade policy and development” . Winters highlighted some key principles, which can serve as a guide to devise UK’s new trade policy and brings its development-friendliness element. First and foremost, the UK government needs to recognize the heterogeneity of its developing country trading partners. While it is impractical to have a unique trade policy for each country, it is feasible to design the policies in clusters, from Least Developed Countries (development-led trade policy) to and the emerging economies of the BRICs (stronger trade-focus).

Winters also mentioned the new trade policy will likely be just trade policy, rather than more comprehensive foreign policy. As a result, the UK has to accept the fact it will lose its ability to influence the policies of developing countries, and of course, the EU too. The government should aim for a simple and pragmatic trade policy with developing countries, to achieve administrative efficiency and conserve the limited resources the government already has to spend on the Brexit related negotiation processes.

How to achieve better trade for development?

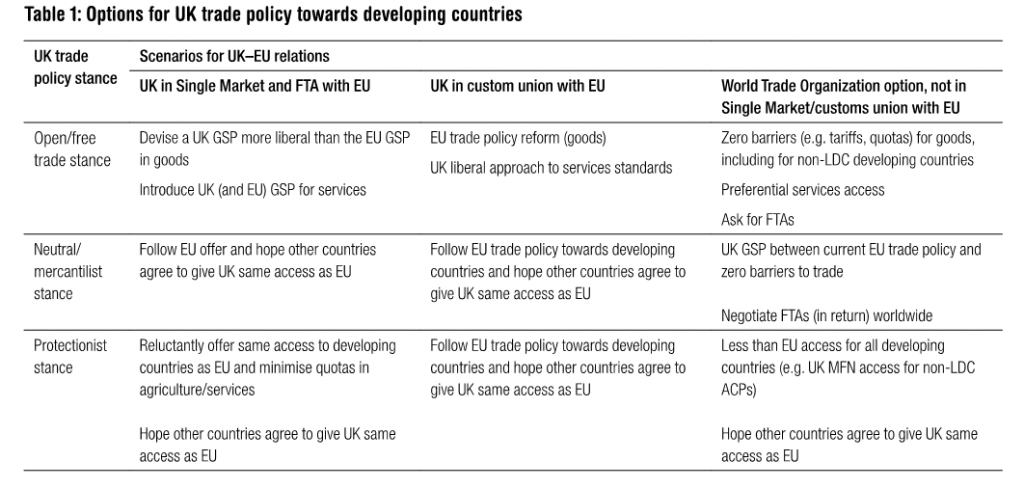

It is crucial for the UK government to continue granting access for development country exporters. Nevertheless, devising a better trade policy for development will largely depend on which post-Brexit scenario takes place. I found the scenarios developed by Dirk Willem te Velde of the Overseas Development Institute to be quite intriguing (see Table 1). Velde develops them by accounting for three aspects: the type of developing nations, the stance of UK trade policy and the outcome of UK-EU negotiations.

The scenario that would result in the least harm to the developing country trading partners is if the UK opts for WTO (and is not in a single market or custom union with the EU) and pursues free trade. The estimates show UK could gain more than the loss associated with Brexit, e.g. by forming FTAs with countries such as Brazil, China, India, and the US. Developing countries on the other hand, would benefit from lower import costs. This option will also require more time to negotiate as it involves pursuing individual FTAs. Thus, constructing transitional arrangements with trading partners, to take effect immediately after formal Brexit, would be important to provide certainty and stability.

Source: Te Velde, D.W. 2016. “Scenarios for UK trade policy towards developing countries after the vote to leave the EU” in The impact of the UK’s post Brexit trade policy and development. ODI and UKOTD.

Now, what are some of the suggestions out there to make the trade policy that would help developing countries? Here are some of the way forwards:

- To go beyond tariff to make the new trade arrangement be development-led, e.g. to discuss the element of anti-dumping standards, migration, labour and human rights).

- To pursue new FTAs with emerging economies including China, Brazil and India.

- Continue to offer Aid for Trade and keep preferential access for the LDCs (particularly the element of Everything But Arms – EBA)

- Remain in the EPAs with African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries

For more details, ODI and UK Trade Policy Observatory (UKTPO) recently launched a collection of essays highlighting some of ideas on “The impact of the UK’s post Brexit trade policy and development”. Here are some of other interesting contributions:

- Mohammad Razzaque and Brendan Vickers discuss “Post-Brexit UK trade policy for international development”

- Peter Holmes re-emphasizes “Aid for Trade as a complement to a new UK trade policy”

- Jim Rollo looks at “A new UK trade policy towards developing countries: what sort of transitions?”

- Simon J. Evenett argues the importance to go “Beyond tariff preferences and trade deals”

Challenges forward

More than ever, UK’s commitment to continue its leading role in global development is being challenged. Development assistance has grown unpopular in the recent decades. The recent referendum certainly gives more room to make the UK more protectionist. The government is resource-constrained to undergo negotiation for the new trade policy. Hence, the challenge from internal politics and other external pressures is immense. Nevertheless, the UK should fight to maintain its legacy as the leading nation for global development. Devising the trade policy which is less favourable than what the EU trade is offering would just mean a step backward to what UK has achieved in the past decades.

Source:

- GDI Public Lecture by Professor L Alan Winters. “Post-Brexit trade policy and development”.

- Mendez-Parra, et al. 2016. The impact of the UK’s post Brexit trade policy and development. ODI and UKTPO. London.