Dr Daniele Malerba, researcher at the German Development Institute for the project, Implementing the Agenda 2030: Integrating Growth, Environment, Equality and Governance and Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Manchester

Like two people falling in love, Development is nowadays rarely seen without Sustainability. And the latter changed the life of the former. For example, the Millennium Development Goals have become the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), culminating in the idea that development needs to be sustainable. But despite its established relevance, Sustainability might not be accepted by some of Development’s friends, for reasons I will try to outline later. Some evidence of this tension was given at the 2017 Annual Development Studies Association conference, the theme of which was “Sustainability Interrogated: Societies, Growth, and Social Justice”. GDI asked the conference participants: “Is sustainability a useful concept in development?” Nearly half of the voters (46%) indicated sustainability is a complicated concept, more than the voters indicating it as a central focus (36%); the minority (18%) did not think sustainability is a useful concept in development. Why is a science-driven concept like sustainability not thought of as useful by everybody? Why do Development’s friends think that Sustainability will not make Development’s life better?

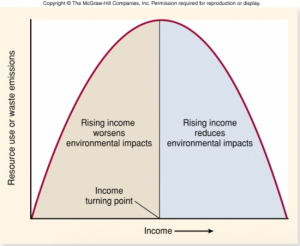

Sustainability is a relative new concept in the policy arena, introduced in 1972 with the report “Limits to Growth” by the Club of Rome. In its original conceptualisation it was meant to underline that infinite economic growth was not possible, echoing neo-Malthusians. But sustainability as a policy concept underwent changes, depending strongly on the economic ideas of the moment. In 1987 the Brundtland Report defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. This definition was broad enough to go hand-in-hand with neo-liberal economic thinking, which advocated the strategy to “grow first and clean later”. This growth-led solution for sustainable development was represented by the environmental Kuznets curve and by the environmental economics discipline, treating the environmental as a mere factor of production. Finally, in its current state, sustainable development is considered as a more complex concept, and that is probably why some do not identify it as a useful concept in development. The complexity is evidenced, for example, by the vast number of goals (17) and targets (169) in the SDGs. This complexity is compounded by the uncertainty of environmental consequences, which make it challenging to incorporate environmental and ecological concerns in widely used development economic models (ecological economics is a first step). Some of the complexity and confusion might also arise from the fact that historically, sustainability has been associated with opposite economic theories, as outlined above.

Sustainability is a relative new concept in the policy arena, introduced in 1972 with the report “Limits to Growth” by the Club of Rome. In its original conceptualisation it was meant to underline that infinite economic growth was not possible, echoing neo-Malthusians. But sustainability as a policy concept underwent changes, depending strongly on the economic ideas of the moment. In 1987 the Brundtland Report defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. This definition was broad enough to go hand-in-hand with neo-liberal economic thinking, which advocated the strategy to “grow first and clean later”. This growth-led solution for sustainable development was represented by the environmental Kuznets curve and by the environmental economics discipline, treating the environmental as a mere factor of production. Finally, in its current state, sustainable development is considered as a more complex concept, and that is probably why some do not identify it as a useful concept in development. The complexity is evidenced, for example, by the vast number of goals (17) and targets (169) in the SDGs. This complexity is compounded by the uncertainty of environmental consequences, which make it challenging to incorporate environmental and ecological concerns in widely used development economic models (ecological economics is a first step). Some of the complexity and confusion might also arise from the fact that historically, sustainability has been associated with opposite economic theories, as outlined above.

So why do Development’s friends think that Sustainability will not make Development’s life better?, Beyond complexity, sustainability can make development more difficult in the short term. There are, for example, clear trade-offs between socioeconomic and environmental goals. Secondly, given these trade-offs, there is a clear problem of prioritisation. This issue involves both policymakers, who need to decide the priorities for their countries; and researchers, who have their own agendas, pressures and priorities to consider.

Despite these challenges, I was a bit surprised by the DSA Conference participants’ answers to our poll. Nearly all of the participants were academics and researchers, and, I assume, believe in the science underlying the urgency of climate and environmental action. I suspect that if the question would have been “is sustainability a necessary concept for development?” the answer would have been overwhelmingly positive. The problem, therefore, lies in the difficulty of an easy definition of sustainability and the interlinkages (trade-offs but also synergies) of the development and sustainability agendas. The way forward is then to improve the systemic view of development within environmental boundaries, instead of insisting work take place with a narrower vision.

The research and academic communities have a crucial role to play in two ways. First, advice on possible trade-offs and synergies between sustainability and development. For example there can be some win-win strategies at the macro level, such structural change driven by green industrial policy; or at the micro level, such as payments for environmental services. Research, as a public good, can play a critical role in showing how making our societies and economies more sustainable represents an opportunity for development goals. But we still need to be careful to propose solutions that benefit most (such as green growth), and be honest in outlining pros and cons of each strategy.

Second, as researchers, we have a strong duty to also show belief in what we preach and write. This means leading also by example and not just by words, as underlined by Kevin Anderson in his keynote lecture at the DSA Conference.

If we think and understand that in the long term Development needs Sustainability to be happy, as Development’s friends, we need to also support them in ensuring their relationship is successful.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.