Pablo Yanguas, University of Manchester

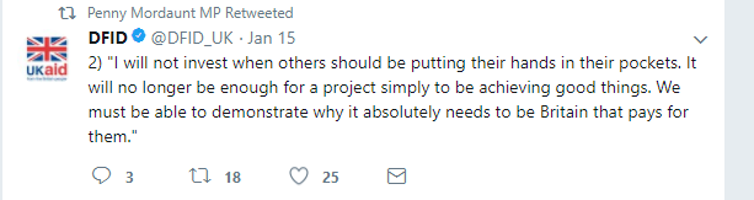

Secretary of State for International Development Penny Mordaunt has warned recipient governments that they face cuts in UK aid if they don’t “put their hands in their pockets”. Her warning is grounded on a claim of public concern: “Nagging doubts persist for many people, about what we are doing, why we are doing it … especially when there are domestic needs and a national debt to address.” It is a compelling point but, as it turns out, one for which there is actually very little evidence.

The most recent YouGov/Times survey poll asked Britons what issues they considered most important among those facing the country: Brexit, health and the economy topped the list. The potential misuse of foreign aid funds, as one would expect, did not even register.

Surveys on public opinion about aid are scarce and often contradictory. While a Telegraph poll in April 2016 found that 57% of people opposed the commitment to spending 0.7% of national income on foreign aid, a Eurobarometer survey later that year found that 55% of respondents in the UK thought aid commitments should be kept and 14% believed that they should be increased. “Nagging doubts”, it would seem, are in the eye of the beholder.

Part of the alleged public concern about aid stems from legislation passed in 2015 by the coalition government that committed to ringfence 0.7% of national income for foreign aid (a decades-old demand from international development advocates). The commitment has resulted in a budget of around £13 billion, a significant figure at a time when other departments cannot rely on ringfenced targets to avoid budget cuts.

Like many others, I am alarmed and appalled by the funding gaps in the National Health Service, which translates into staffing problems and lower quality of care. In this context, it is not unreasonable to wonder whether an extra £13 billion could help save the NHS by increasing the level of spending – tripling the kind of boost that experts recommend.

But once we start down this path we need to also examine other public expenditures. The Trident replacement programme, for instance, costs £41 billion and I have yet to see a persuasive argument for why four nuclear submarines are more important than a functioning NHS (whereas UK aid is effective both on humanitarian grounds and as a source of strategic influence).

But of course, that would be a tough public conversation to have. Whereas aid talk, for politicians, is cheap.

A more honest conversation

Even if we discount Mordaunt’s claims about public concern, the larger point remains that the UK should consider the commitment of its development partners to build sustainable public services. Aid emancipation should be the ultimate priority of development assistance and it is not a bad criterion on which to judge the relative usefulness of foreign aid. That being said, there are three caveats to this argument.

The developing world is seeing a growing gap between those countries that can finance their own development and those that cannot. Aid is still a necessary resource for those weaker states with no fiscal capacity or access to private finance.

Penny Mordaunt watching dancers in the village of Pichelin on Dominica in 2017. Victoria Jones/PA Wire/PA Images

Humanitarianism remains a valid argument for spending foreign aid wherever it can stop the spread of disease, displacement, or violence, especially when recipients are unable to cope with sudden shocks caused by pandemics or refugee flows.

Most importantly, it is actually very hard to determine whether a government is not “putting its hands in its pockets” out of capriciousness, mismanagement, inability, or unwillingness. Consider the UK itself: why is the NHS underfunded? Is the British government “failing to invest in its own people”?

These are just some of the questions that I would throw back at Mordaunt as she ponders where UK aid should be heading. The public debate about aid in donor countries like the UK is largely disconnected from the realities of development on the ground. Bridging this gap requires an alternative way of thinking about the politics of change. One that does not draw such a crisp distinction between the taken-for-granted messiness of our own policy-making and the kinds of capacity and commitment that we demand from aid recipients.

![]() Like Mordaunt, I too believe in aid. And like her, I believe that the UK should work with partners to ensure that aid feeds into sustainable, effective and accountable states and markets. I am sure that she is a moral person and that she means well when she invokes the concerns of British taxpayers. But a political leader’s responsibility isn’t just to represent, but to lead and educate. And while Mordaunt raises some good questions, the British public deserves better, more honest answers.

Like Mordaunt, I too believe in aid. And like her, I believe that the UK should work with partners to ensure that aid feeds into sustainable, effective and accountable states and markets. I am sure that she is a moral person and that she means well when she invokes the concerns of British taxpayers. But a political leader’s responsibility isn’t just to represent, but to lead and educate. And while Mordaunt raises some good questions, the British public deserves better, more honest answers.

Pablo Yanguas, Research Fellow, University of Manchester

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.