Students on the MSc International Development programme travel to Uganda each year to conduct relevant research projects:

In the final blog post in the series by students, Emily Olson examines if universal access to primary education means that more children are learning.

By Emily Olson

As we walked into the inner courtyard, children were spilling out of the packed, dark classrooms and running towards us. One teacher walked around with a stick herding them inside to where they attempted to peer at us through small windows and doors.

The Bweyale Modern Primary School is a private school 224 kilometers north of Kampala. Located near the Kiryandongo Refugee Settlement, the 672 students live as boarding students with the school or with their families in nearby mud huts or small cement buildings without electricity. While speaking with the Assistant Head Teacher, he listed many of the needs of their school. “There are not enough desks or benches. We need better water. We need books.”

Bweyale Modern. Photo Credit: Kate Hollis, 2015.

The need for more supplies was apparent. However, he believed this private school offered a higher quality education than free public schools stating, “In my opinion, the difference between a public school and a private school is that private schools have monitoring and public schools do not.” We asked the last time this school was monitored and he replied, “The director visited today for the first time in a year. He will be getting us desks and benches.” Throughout our discussion we began to see there was a stigma associated with public schools. Even this struggling private school was believed to be better.

Bweyale Modern. Photo Credit: Kate Hollis, 2015.

In a country where there is a free Universal Primary Education policy, why would parents choose to pay to send their children to private schools when they are provided with free public education? Many families receive food rations from the World Food Programme, and yet the private schools with expensive tuition costs are overcrowded.

We asked this question multiple times throughout our time in Uganda and the same answer was given repeatedly. One woman said she would never place her daughter in public schooling. Referring to the UPE she said, “People are starting to realize it has been a failure.” One man said he would much rather go to sleep hungry then send his children to public school stating that the quality of public school is different. “Public school doesn’t provide enough education,” he said. Another woman said she would never put her daughter in public education. Instead, she sent her daughter to Kampala, nearly 213 kilometers away, to live with a brother-in-law because she could not afford private primary school tuition fees.

This blog examines the poor quality of UPE funded education and the resulting negative perceptions and stigma attached to public primary schools. Because of the low quality, this is leaving many poor and marginalized children without an acceptable option for their education. In my initial research, the UPE policy appeared to be well viewed and incredibly successful in providing education to poor and marginalized children. However, during this recent fieldwork trip, a different picture was painted as a majority of the poor and marginalized I spoke with believed public education would inhibit their child’s future and would continue the cycle of poverty. The most common explanation for this view was the lack of effective learning as evidenced by low test scores and high student-teacher ratios. By examining these two issues, we will see that despite the high enrollment in UPE, it simply cannot benefit its targeted students without modification of policy implementation and policy practice.

Low Pass rates

Theoretically, the reduction of tuition fees should provide all children the opportunity to receive an education, progress and hopefully continue on to receive further training for a career. Within the first seven years of UPE implementation, the Ministry of Education reported an increase in enrollment rates by 171 percent. While these rates show there was a greater access to primary education, they did not display how many students were struggling to complete and continue schooling into secondary levels. Uganda’s primary school consists of levels P1 to P7. According to a SACMEQ study concerning educational quality in Southern and Eastern Africa, P6 students in Uganda were far behind average learning levels of other countries including neighboring Kenya and Tanzania.

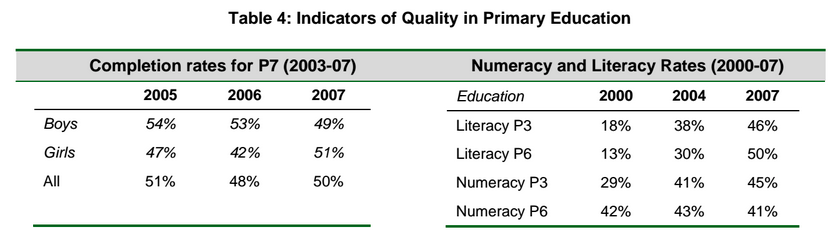

In order to continue on to secondary school, a compulsory exam must be taken and passed. The ODI reports that despite the number of enrolled children doubling, the passing rate has only marginally increased. Table 1.1 demonstrates this low increase in passing and completion rates. By 2007, only half of students nearing the end of their primary education were literate.

Table 1.1 Indicators of Quality in Primary Education. Source: Hedger et al. (2010).

An ODI Education Sector Budget Case Study of Uganda in 2010 noted “the primary education sub-sector has exhibited persistent weakness in the quality of education as measured by learning achievements such as literacy, numeracy and test scores”. The poor quality of education and the lack of proper resources created a direct impact upon the students’ educational value, learning and overall performance. In the results for mathematics, test scores dropped from 48% to 31% during the 1996 to 1999 period. During this same time, English test scores dropped from 92% to 56%. In 2001, over 100,000 students failed to pass the primary school test allowing them to enter secondary school. This caused what was termed the “UPE bulge”.

The low passing rates prove the students have not been taught the information they have needed in order to perform well in testing. This has led to a greater negative perception of the UPE policy. A primary school head teacher said that less than 5% of her students were likely reach university because of their inability to pass these tests. Studies show that without further education, UPE students will remain in poverty. In order for the UPE to be successful, it must more effectively prepare students to pass tests and eventually continue their education.

High student – teacher ratios

Another issue causing a negative perception of the UPE is the high student-teacher ratios. After the introduction of the UPE, the student-teacher ratio in Ugandan primary schools became among the highest in the world.

One school we attended was an exception to the extremely high ratios. Funded by both the government and NGOs, their classroom size was only an average of 31 students. There was much more time for interaction and the students we observed seemed to understand the lesson very well. As I sat at a table with some of the students towards the back of the classroom, the teacher was calling out instructions. “Write this math problem in your books. Once you have solved the problem, raise your hand so I can come by and check it. Do not move on.”

The children at my table sat for over 10 minutes with their hands raised without having a chance for the teacher to come check their work. As I thought about the average class size in Ugandan schools that do not receive similar NGO funding, it was clear why over 50% of the students were leaving primary school illiterate. If students are not getting the time and attention they need in a classroom of 31 students, it will certainly be difficult to succeed in a classroom double that size.

Interaction with a teacher is a crucial part of learning. In Uganda, with an average of over 50 students per classroom and a reported 100 students per teacher in some rural villages it becomes extremely difficult for the teacher to provide the individual attention needed. According to Deininger, the “counter-productive impact of such high ratios is illustrated by the fact that nationally only three quarters of the students who took the final primary examination in 1999 managed to pass this test.

To ensure sustainability of the accomplishments [of the UPE] improvements in education quality will be required”. The high student-teacher ratio also creates stigma attached to public education. The head teacher of public schools said this is the very reason why there was a large migration from public to private.

Conclusions

Primary education has clearly become more accessible with the UPE. Unfortunately, the UPE is also viewed as ineffective because of the poor quality associated with it. Dr. Yusuf Nsubuga, the Director of Basic and Secondary Education at the Ministry of Education stated, “Any loss in quality is an inevitable, but temporary consequence of expanding access. Globally, whenever there is mass education, in the first years you have to face the challenge of quality”. This poor quality has continued now for over 18 years and is reflected in multiple aspects of education. With low passing rates and high student-teacher ratios many are looking elsewhere for an education that will improve the future of their children.

In order for the UPE to effectively help children, the government must more effectively implement policy to encourage schools to properly teach subjects and provide an education with teacher interaction and smaller classroom sizes. By doing this, it will better prepare children for further education and provide a greater opportunity to leave the poverty cycle.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks