Jonathan Stephen, MSc student, Global Development Institute

This blog translates some of the key discussion points raised in my MSc Dissertation looking at LGBTI exclusion from development and, in particular, multilateral organisations. My research asked if development is ready ‘to come out’? I used the LGBTI Inclusion Index to evaluate the nature of LGBTI exclusion in development and the declaration to leave no one behind. Steered by this dilemma, the research uses the UNDP and World Bank’s publication of the LGBTI Inclusion Index to interrogate the quality and inclusive nature for LGBTI citizens to participate in the design and delivery and subsequently, feel the benefits of the index.

I refer to LGBTI simplicity and assume marginalised sexual orientation, gender identity/expression and sex characteristics (SOGIESC) citizens are included when referring to LGBTI matters. I recognise that citizens who share marginalised SOGIESCs but may not identify as LGBTI are distinct, and it is important to explore LGBTI exclusion in their own right.

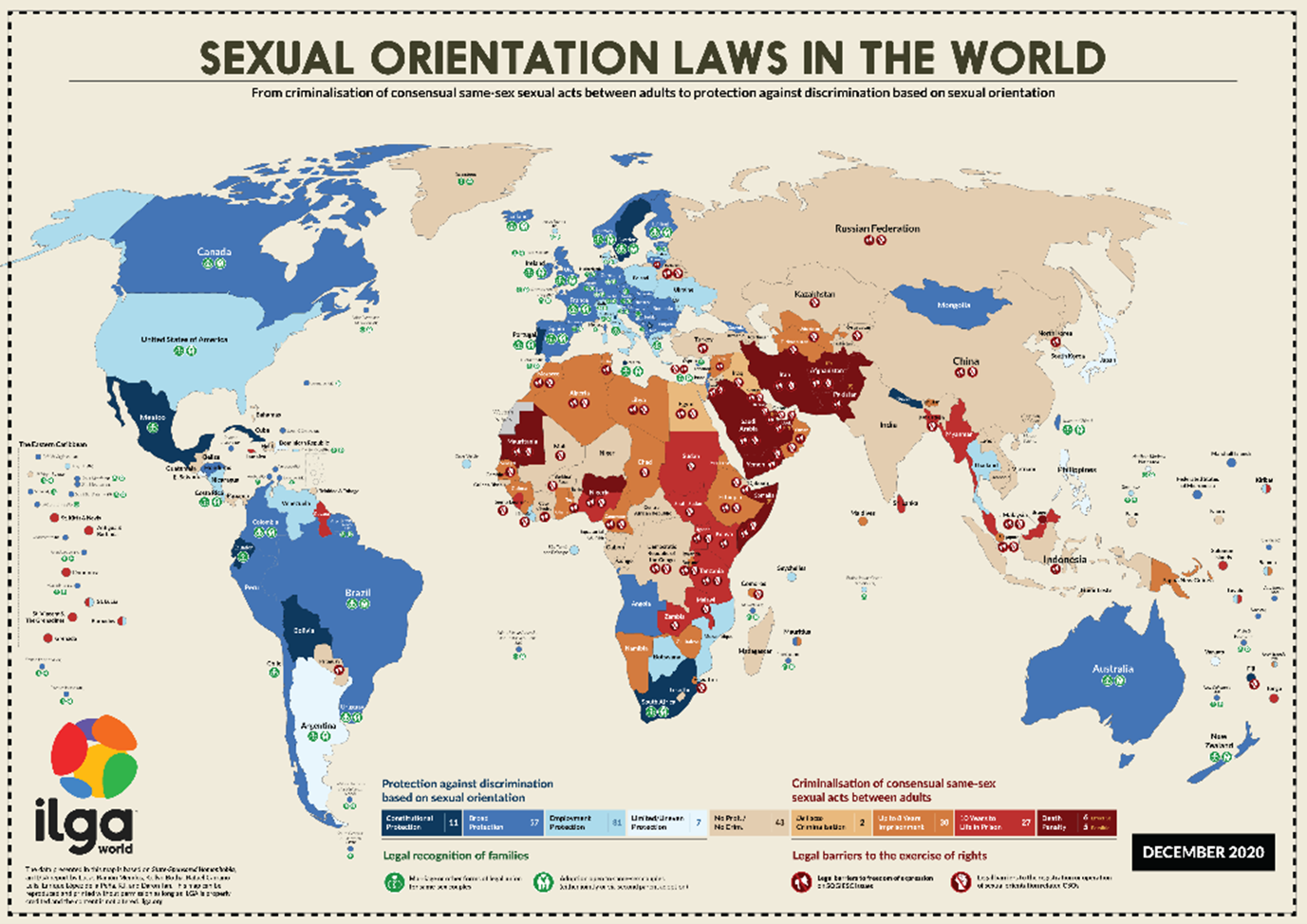

As documented by the OECD, Approximately 17 million LGBTI lives (of those we know of) are disregarded socially, economically, in health and wider, with some examples being threats to labour security, housing, the fragility of human rights and the death penalty. The World Bank documents that LGBTI citizens continue to experience discrimination, violence, and threat to life across the world (an indication of the global scale of the matter):

- LGBTI citizens experience lower educational outcomes, higher unemployment rates and a lack of access to adequate housing, financial and health services

- LGBTI citizens risk of poverty due to discrimination

- Lack of data reflecting the lives of LGBTI citizens

- LGBTI citizens threat to life is a real concern with 70 countries continuing to criminalise homosexuality

- The detrimental impact the COVID-19 pandemic is having on service delivery for marginalised groups such as LGBTI citizens in accessing necessary services

Continuing with the global framing, LGBTI citizens are not framed explicitly in the UN’s SDGs and associated targets. It is of the assumption that LGBTI rights could be aligned to ‘other status‘ via the SDG goal 10 – reducing inequalities; with the target details being “reducing inequalities in income as well as those based on age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status within a country.” The lack of LGBTI acknowledgement in the SDGs explicitly calls into question why and how this may have been decided and who benefits from the absence of LGBTI inclusion.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) recently shared: A Set of Proposed Indicators for the LGBTI Inclusion Index. My research employs qualitative methods using this LGBTI Inclusion Index as a case study. It explores how multilateral agencies like the UNDP respond to exclusion, or absence of inclusion, through the investigation of LGBTI exclusion in development. Whilst assessing opportunities to ensure no one is left behind. The index explicitly recognises LGBTI in its discourse and its aims for LGBTI inclusion. It is also unique given it is the only global measure to date dedicated to LGBTI inclusion. In addition, the LGBTI Inclusion Index provokes excitement in addressing the existing tension vis-à-vis LGBTI exclusion. With that said, the index is a valuable item for scrutinising the protocol in relation to participation among LGBTI citizens and responding to a gap in activities from the UN, such as the omission of LGBTI citizens from the SDGs.

The Five Dimensions of the LGBTI Inclusion Index. Source: Badgett & Sell (2018).

The LGBTI Inclusion Index may have been created due to the worrying absence of LGBTI citizens’ inclusion among the SDGs and the translation into addressing inequalities in and across development activities. Perhaps, a move to ensure that multilateral agencies with intergovernmental powers and the promise of leaving no one behind is not perceived as being neutral, distant and ingenuine in terms of LGBTI inclusion. This point raises some important questions about how multilateral agencies continue to engage with states that are resistant to or rejecting LGBTI citizens.

It could be that multilateral agencies are genuinely concerned about LGBTI exclusion and their type of role in responding to this. However, it could also be two-fold, with concerns relating to the likes of the UN’s legitimacy being undermined vis-à-vis leaving no one behind, except some. This, therefore, raises the question as to the extent to which multilateral organisations like the UN, UNDP, and World Bank have responded to and are addressing LGBTI exclusion conditions globally.

More specifically, if the likes of the World Bank, UN and UNDP continue to engage with states that disagree with LGBTI citizens’ inclusion, they risk undermining their legitimacy as LGBTI advocates and influence in addressing LGBTI exclusion. Therefore, associated questions arise as to whether the likes of the UN, UNDP and the World Bank are the appropriate multilateral development organisations to steer the LGBTI Inclusion Index.

In addition, the research argues the index itself is exclusive in its participatory research methods, which resonate with the Human Development Framework and extends upon the thought of Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach. Arguing that the LGBTI Inclusion Index methods are theoretically contradictory in their efforts to welcome and nurture inclusive participation of all LGBTI citizens, not just of experts. This subsequently raises questions in terms of the index’s ability to address the exclusion of all LGBTI citizens globally.

Though the thesis does not necessarily offer LGBTI policy inclusive solutions, it does propose potential improvements, including the scope for the UNDP and World Bank to revisit the theoretical premise to strengthen transparency on who is able to participate and who is not. As well as revising the LGBTI Inclusion Index participatory dimension to establish alternative ways for all LGBTI citizens to participate in the creation, design and implementation of the index and associated programmes among development agencies. Whilst also realising and feeling the benefits with recognition toward the complexities of differing contexts. Maybe an additional predictor of the index is identifying the absence of inclusive LGBTI participation across contexts to better address/overcome differing conditions of LGBTI exclusion.

Pertinent to my research and contributing to the limitations of this work, the degree to which the LGBTI Inclusion Index affects LGBTI exclusion is unknown, given the index being recently established. Nevertheless, the index is an important item to continue to follow when examining LGBTI exclusion in development and how development agencies will utilise the index to contribute to programming decisions.

Ultimately, LGBTI exclusion is a complex and dynamic landscape that has parallels from the global North and South. In particular, the absence of inclusion and the fragility of LGBTI inclusion in relation to participation raises the question that development may be and has been conservative, for too long, when it comes to addressing LGBTI exclusion, illuminating the question – is development ready to come out? Here, the LGBTI Inclusion Index may steer a critical role for LGBTI citizens’ inclusion and sense of belonging in development.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.