By Diana Mitlin

A recent conference on African Urbanism has provided a useful space for me to reflect on what the African experience has brought to my work and that of my colleagues. This has included academic scholarship, professional and policy engagement and activism. Given their potential to improve development in Manchester and the role the University plays in this, two lessons are immediately worth sharing.

1 – Grassroots action and community mobilisation

My first engagement with the richness of grassroots actions in African neighbourhoods to address interventions was in 1993, when I took part in a meeting of informal settlement leaders in Cape Town. These were, for the most part, residents who had been ignored by the organisations which represented residents legally entitled to live in Black townships. It was also shortly after activist Chris Hani was assassinated by a right wing extremist. The meeting had originally been planned to be held in an informal settlement but in this traumatic context, the scale of unrest meant that community leaders from elsewhere were not comfortable visiting informal neighbourhoods.

What was immediately apparent was the depth of community care – with activists who interspersed discussion by articulating their grief and fears, and a coming together in regular song throughout the meeting. Also evident was their ability to both recognise the significance of the accountability of leaders to members, and their interest in new tools and approaches to open up alternative development options.

Over the next months, the community leaders – already active in following up ideas about SDI savings groups (originally crafted in India) – agreed to network their groups and create the South African Homeless People’s Federation.

And over the next two decades, the ideas shared in this meeting have spread across Africa – with other informal settlements in Asia and Latin America also experimenting with these tools and methods. In 1996, the network Slum/Shack Dwellers International was born, linking these national federations into a transnational group.

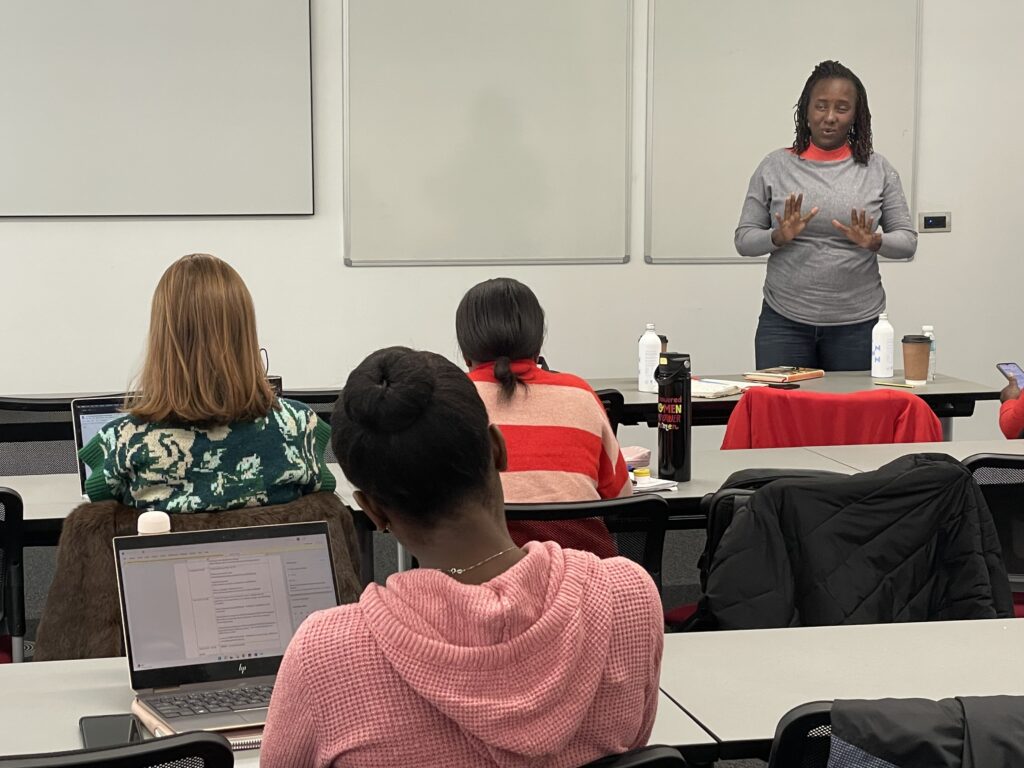

SDI teaching in Manchester, 2022

An articulate representation of what this approach offers to poverty reduction was explained to me by a women in a small town in Namibia, Omaruru, during a group discussion about the experiences of SDI organising:

“Before I was a member of the savings scheme, I was alone. Now I have a friend in every house on the street. When Namibia became independent, I did not feel independent. Now I can go into the office of the governor.”

Much of the academic literature on SDI focuses on the experiences and consequences of externally funded development interventions. But relatively little captures the experiences in smaller towns or more isolated neighbourhoods, where there is relatively less professional support and fewer opportunities for externally funded interventions.

One core premise of SDI is that poverty reduction programming needs to be reworked from below:

- Organising processes need to be redesigned to strengthen accountable community groups (often via saving schemes).

- Groups need to be networked to enable citywide strategising and avoid residents’ associations being played against each other (by federating).

- Mobilisation needs to be built across all residents in each neighbourhood and across the city (though data collection with settlement profiling and household enumerations).

- Peer-to-peer learning (to build confidence, capabilities and reduce the power of professionals).

- New modalities of poverty reduction need to be designed, tested through implementation and refined (involving co production with local authorities and other state agencies).

- The community networks need sensitive and strategic professional support to link to city council officials, to:

- Document learning for external audiences.

- Raise funding from donors for networking, data collection and project experimentation.

- Provide or contract project professional expertise, and supporting learning (absorbing failures, anticipating difficulties and blockages that will emerge).

African approaches inspiring Manchester community organising

Annual visits of SDI Federations to The University of Manchester from 2011 linked to GDI’s teaching programming provided a platform for the sharing of these ideas with community groups in Manchester. Over time a local network, Community Savers, has developed with its own support NGO (CLASS).

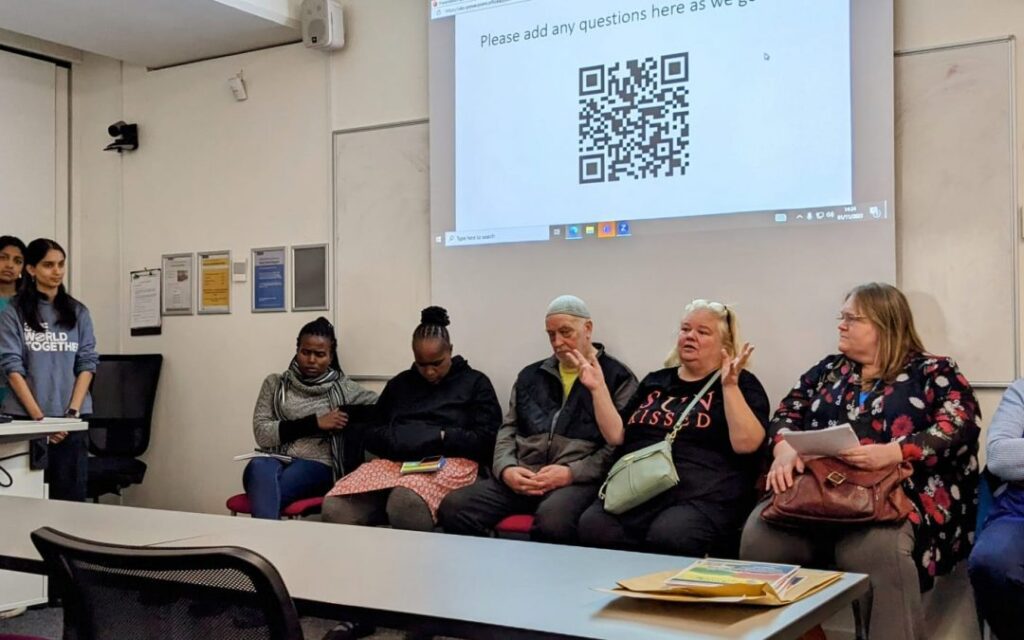

Community Savers and SDI Kenya members speak on a panel at The University of Manchester in 2023

Community Savers has been supported by multiple engagements with SDI – first from South Africa and then spreading to Kenya – which have catalysed community leadership in Manchester (and now also in Sheffield) in a way that replicates processes in Africa. While I am always nervous to claim that things are unique, what is clear is that for a group of mainly women leaders – who have long resided in low-income neighbourhoods, and previously been ignored by many external agencies – this organising methodology is different from what has previously been offered and makes sense to them.

From 2016, a group of women’s led community groups in Greater Manchester began a more deliberate path of peer-to-peer learning with Kenya. Supported by the emergence of a small professional team and the formation of a charity, CLASS, these ideas have been taken forward.

In just eight years, nurtured by this reversal of learning hierarchies, African practices have catalysed a strong, vibrant, community-led movement in both Greater Manchester and Sheffield. Just as in Africa, academic expertise has been used (where appropriate) to challenge exclusion and enhance the legitimacy of community demands – and amplify the scale of the community voice.

The African context – with limited community accountabilities, inadequate public services and socially distant local authorities – has nurtured approaches to addressing poverty and inequality, which maintains relevance when transferred to the UK.

2 – The potential of urban reform coalitions

My second example is homegrown African learning about urban reform coalitions, which are challenging poverty and inequality in the continent. This practice is potentially of interest to The University of Manchester, as it builds a new strategy for a civic university that is suited to the challenges of urban development the 21st century.

City-based coalitions have previously been associated with business and local authority elite deals to strengthen economic opportunities in cities. Yet these are often at the expense of low-income groups, who may be displaced by infrastructure improvements, and who are rarely included in these deliberations.

African practices have built on innovations within and beyond Africa to experiment with coalitions and alliances that seek to find new development options to strengthening inclusion and accountability. Universities are important here. They act both as hosts and/or support processes located outside academia. Examples include the Urban Action Lab at Makerere University in Kampala, the Sierra Leone Urban Resource Centre in Freetown (linked to Njala University as a catalyst), the Urban Informality Forum in Harare (with the University of Harare as co-founders), and the Centre for Housing and Sustainable Development at the University of Lagos. More short-term efforts include the Mukuru Special Planning Area which included academics from the University of Nairobi and Strathmore Law School (Kenya) as well as UC Berkeley (US). And now, institutionalised efforts include Municipal Development Forums in Ugandan towns and cities.

These initiatives share common features. They are orientated to a more just and inclusive city that address the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and more. They recognise that informality – both in terms of the economy and residence – is a way of life for the most marginalised and disadvantaged urban residents. More than 56% of residents live in informal neighbourhoods across sub-Saharan Africa, and in most cities, more than 80% of workers are informally employed or informal entrepreneurs. It is clear why this is a major area of attention.

Such coalitions include multiple stakeholders – including the private and public sectors – who all have an interest in improving urban performance. The common experience in the examples above is that local government responds well to these initiatives. Governments are reassured by the inclusive multistakeholder approach to addressing poverty and inequality, and redefining economic growth options so they benefit all. Academics provide essential knowledge, and help to reassure all parties that there is space for debate and discussion of potentially contentious issues.

Such coalitions are changing the dynamics between academics, professionals and local authorities, and the communities whose development is the purpose of these platforms. Experience suggest that they contribute in multiple ways, two of which we highlight here.

- Accountability

Academics and professionals are rarely accountable to the communities for the work that they do. Communities are frustrated with being researched with no tangible increase in development options. They feel used – conscious that they are providing the knowledge that academics use to write papers and secure personal advancement – without being either recognised or benefited. And they wonder who determines research priorities and why their communities’ needs and interests are not addressed in these knowledge processes. Bringing diverse community groups together through coalition meetings, and sharing information across these networks improves the accountability of academics and professionals to the disadvantaged marginalised groups they seek to help. These spaces are not so that communities can comment on academic priorities, they are there to co-create a new way of engaging around a common agenda.

- Information and knowledge

The mantra “information is power” is widely repeated. Less frequently repeated is the use of disinformation and partial information to disempower, manipulate and control. Many grassroots leaders are denied the information they need to act effectively and strategically in addressing the needs and interests of their members and other residents or workers. Participation in urban reform coalitions helps community leaders because they are connected to well-informed individuals. The academic presence helps to ensure that coalitions are public platforms placing information and knowledge, with the public space facilitating a rich discussion.

What can we in Manchester learn from this African experience?

I suggest two main insights to consider.

First, the UK context is one where academic and professional expertise has failed to address structural poverty and been seen to fail. The populist turn to politics is associated with an anti-expert narrative, offering promises of inclusion that are not dependent on knowledge and evidence. The danger of this is self-evident.

Local reform coalitions can provide a tangible basis that challenges this narrative and the practice of expert failure. A closer engagement, incorporating multiple stakeholders, results in a rich dialogue between academics and organised communities.

Knowledge priorities from communities can be presented, discussed and potentially addressed. The engagement of the local authority helps to ensure that a more equitable relationship is nurtured between such communities and the councillors and city hall. The presence of academics serves to legitimise and amplify the community voice.

Neighbourhoods proximate to the university may be invited to change their relationships, address their frustration with their elite neighbour and define new options for collective development, student education, individual employment and co-management of space through this collaboration.

Second, discourses of the civic university in Manchester to date have often been centred on the relationships between the university and local government. As shown by the examples from Africa, there is an alternative practice in process – one with a more inclusive understanding about who should shape development priorities and solutions.

The rapid urbanisation process in Africa has highlighted major spatial and social inequalities. But it has also provided an opportunity for academics who want to address them to raise their game, through inclusive urban reform coalitions.

Coalitions provide an opportunity to aggregate academic efforts, and make space to respond to the interests, demands and needs of other residents in the city. In Manchester, as in African cities, there are a multitude of individual academics who prioritise these themes in their work. However, institutional processes have often fractured rather than aggregated their efforts – resulting in marginal benefits to those living in local neighbourhoods.

The extensive experiences of African academics and urban reformers shows us what is possible, and how engagement with both local communities and councils can transform inner cities for the better.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Please feel free to use this post under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Full information is available here