David Little

Much of my career has been spent trying to find ways of reducing the environmental pollution and social damage caused by oil spills. In recent work with colleagues at Manchester and Vancouver, we have shown how prolonged public pressure brought genuine improvement to oil spill response (OSR).

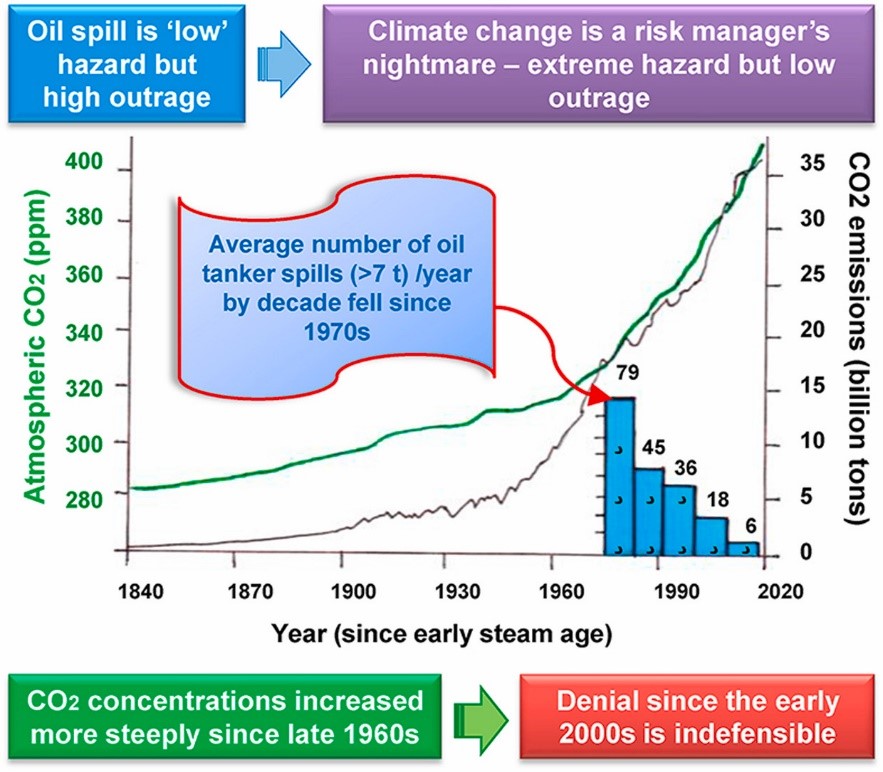

But that got us thinking about oil spills and climate change (see Figure 1). In particular: “why does a low-probability risk like an oil spill attract huge public outrage, whereas climate change presents global, extreme and multifarious risks but little or no outrage? That is, until recently, and mainly among young people.

Source: Little, D.I., Sheppard, S.R.J., Hulme, D., 2021. A perspective on oil spills: what we should have learned about global warming. Ocean & Coastal Management 202:14 pp.

Visibility

Climate change and its causes have not been easily or widely visible. With photographs of dead and dying marine wildlife, oil spills have always had the perceptual ‘advantage’ of being messy and obvious. For most people, it seems climate change has not yet found such an undeniable and photogenic hook, whilst global warming is often met with responses from the general public such as “it’s something scientists do, not us”!, or even “bring it on!”

No-one wants oiled Puffins or dead seal pups. By focussing on the sub-issue – how we can reduce the impacts of oil spills – we are deflected by accident or design from tackling the big issue – which is how on earth do we stop burning oil?

Excessive Consumption

Rather than simply expecting government and industry to make OSR innovations and improve resilience to spills – often limited to richer countries – we would have to look at the day-to-day ‘oil spills’ that we all cause. By this we mean driving gas-guzzling cars, buying products in plastic packaging, not insulating our homes, and jet-setting about the globe – if and when it’s possible again.

With Covid-19 and successive pandemic and security threats, whether we like it or not, mass behavioural change and collective action are coming. Otherwise, “selfishness, greed and apathy” will continue to reign supreme, facilitated by nationalism, populism, and topped off with downright criminality.

Remembering that the OSR improvements we have documented took more than 50 years, the present levels of critical thinking, emotional intelligence, social mobilization, and public pressure cannot fix the climate crisis. Our concerns arise from the damage that ‘business as usual’ has done – and is doing – to our kids and grandchildren, not to mention the scandalous situation of the world’s poor and displaced.

The lies and deception of leaders around the world in recent years are now in plain sight, and should be unacceptable. The world’s economic system is unfit for purpose to meet these challenges. Politicians and economists seem powerless without their usual assumption of never-ending growth – utter madness! We need a new politics and new economics, underpinned by better understanding of our place in the natural world.

Personal Choices

With this comes personal responsibility for change – always the hardest – choosing to eat less meat and reducing air and road travel. Meat production has 40 times the greenhouse gas (GHG) footprint of vegetables or pulses. Food shipment ‘air miles’ are 100 times larger than their GHG footprint when shipped by sea. These high ratios illustrate the leverage we can exert individually by everyday consumer choices that reduce demand for ‘cheap’ oil.

The need for such ‘cathedral thinking’ to solve the climate crisis was nailed over 400 years ago by Christopher Marlowe. In the central section of ‘Doctor Faustus’, he is tempted by Mephistopheles with out-of-season exotic fruits. Like the greedy Faustus, in the end we will pay for our entitlement to luxury, international travel and power. Although the outlook is overwhelmingly pessimistic – especially for the poor – a philosophical shift from our exceptionalism is welcome and underway, exemplified by Mark Carney’s Reith Lectures.

Ethical Decisions

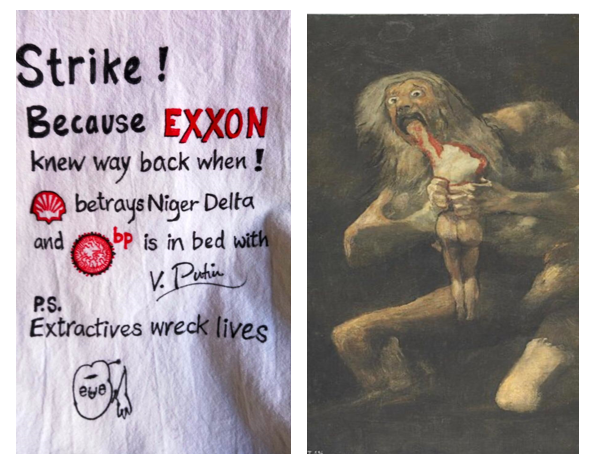

Some financial experts have clearly made progress with more ethical decision-making by encouraging investment in the ‘good guys’. However, if you read our own article’s central section which covers the nasty situation in the Niger Delta oilfield, you will see that Archbishop Welby has not convinced us that avoiding investment in the ‘bad guys’ is truly underway. Last time we checked, his new firm (Church of England) still invests in his old firm (Shell) – hardly an ethical decision.

Our recovery from Covid-19 has to be green and equitable, without reliance on the usual suspects. Blind enthrallment to gross domestic product (GDP) in pursuit of growth and vanity projects will be a hollow victory. Recent articles in The Guardian contend we must go way beyond low-carbon accounting tricks such as emissions-trading on carbon that’s already been emitted. The oil & gas industry must acknowledge fully the health and climate impacts of its operations, rather than prolonging them by pitching its ability to produce hydrogen.

Politics

The UK presidency of the COP26 climate summit (Glasgow, Scotland 1-12 November) is being advised or lobbied by energy consultants, as the ‘Get Brexit Done’ cabinet belatedly prepares for COP26. We obviously support Alok Sharma’s recent sense of urgency to avoid climate catastrophe – only 9 years left to cut carbon emissions in half – but apart from ending the sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles by 2030, he doesn’t specifically mention the oil & gas industry.

He really doesn’t do justice to foreign aid either. This is no surprise, given its recent reorganisation under the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO). Such reorganisation promises closer integration of UK foreign aid with the business interests of ‘global Britain’, including fossil fuels, not to mention weapons. Mr. Sharma alights fleetingly on the role of early warning systems for tropical cyclones – fair enough – but doesn’t emphasise the far broader steps needed to improve climate change adaptation in the global south (institutional capacity, disaster preparedness and community resilience).

In this year of UK leadership in COP26 and the G7 summit (Carbis Bay, Cornwall 11-13 June) when all ducks should be in a row and planets aligned, instead we risk offering hubris, hypocrisy and incompetence. We shall need more than English ‘derring-do’ to reach the goal of global ‘mend and make-do’.

Realpolitik

More equitable access to social justice is essential to mitigate vulnerability both to oil spills, pandemics and climate change. We’ve been disabled politically by climate change deniers (from Nigel Lawson to Donald Trump) and their tactics of delay and deception. Industry and governments have of course often engaged in realpolitik. A few examples follow. Despite non-intervention policies, at least 7 multinational corporations supported the 1936 fascist uprising in Spain. Anglo-Iranian oil in cahoots with UK and US intelligence agencies connived in the 1953 coup to overthrow democracy in Iran. It was inevitable in post-colonial Africa that Kaiser Alumina and Lonrho (Ghana), Lonrho and Glencore (Copper Belt), and Shell and ENI (Nigeria) were carefully aligned with their host governments’ priorities, for better or worse.

Despite current attention to environmental, social and governance (ESG) audits of supply chains, many businesses today are deliberate or unwitting parties in similar deals. Precisely because they are neither sustainable nor equitable; extractive industries can undermine democracy and security in the world’s poorest nations.

Mining cobalt, copper, lithium and rare earth elements for the renewables sector is of course key to solving a global climate crisis driven by hydrocarbons – unfortunately, the real-world effects of such minerals production on local communities can be equally damaging to those of oil & gas.

Sources: (left) Photo by David Little during climate strike, Zaragoza, Spain, September 27, 2019; (right): Goya (1820) Saturn Devouring his Son.

Our perspective on the evolution of OSR suggests that the major oil spill clean-ups are likely to be seen by history as ‘greenwash’ – to placate the oil industry’s rich-world customers and shareholders. The sorts of contingency planning tools exemplified by OSR are useful models as each sector develops specific climate emergency plans and incident-command systems.

At present, with only a nod to the scale of the problem, this is glaringly insufficient to deal with the contribution of the oil industry to climate change. Right now we cannot see the wood for the trees. Nevertheless, oil spills could have been our landmarks to the global warming crisis, to help us urgently recognize that “we need a cultural and spiritual transformation” to accelerate decarbonisation.

- David Little recently appeared on the GDI podcast where he was interviewed by David Hulme.

- Read a transcript of the podcast

Source: Photo by Christopher Kao on Unsplash

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole