Kitty Lymperopoulou and Lindsey Garratt on migration and families in Europe

The House of Commons has cleared the way for the Prime Minister to trigger article 50 at the end of March 2017, however, what happens next for EU citizens living in the UK post Brexit? Here, Dr Lindsey Garratt and Dr Kitty Lymperopouloufrom The University of Manchester recount the recent Migrant Families in Europe conference and discuss the associated policy issues and their plans for influencing decision makers throughout the Brexit process.

- EU citizens living in the UK and their families are facing the prospect of increased barriers to live and work in the UK

- Current debates on migration are rarely discussed from the perspective of the family

- To address this the Centre on Dynamics of Diversity hosted a two-day conference focused on broadening the conversation beyond traditional understandings of ‘family migration’

- The conference highlighted the disconnect between policies and practices relating to migrants and the experiences of migrant families in Europe

- As the government enters into Brexit negotiations about the rights of movement of EU citizens and settlement in the UK, it is the interests of families that need to be understood and protected

Two amendments suggested by the House of Lords have been rejected, including the protection for EU citizens’ rights to remain in the UK. EU citizens living in the UK and their families are facing the prospect of increased restrictions and barriers to live and work in the UK. But despite the significance of families in the movement of populations to and within Europe, current debates on migration are rarely discussed from the perspective of the family.

Migration and Families in Europe – Conference

To address this Centre on Dynamics of Diversity hosted a two-day conference entitled ‘Migration and Families in Europe: National and Local Perspectives at a Time of Euroscepticism’. Our aim was to bring together scholars, practitioners and policy makers from the UK and Europe to discuss the complexity of migration and what it means for families in the current political climate.

The theme of this two day conference was ‘migration and families’ to purposively broaden discussion beyond family migration, which has tended to be defined as migration for family unification only.

The first day focused on conceptual and methodological challenges in researching migrant families. These ranged from cross-national surveys, longitudinal and case study methods, to participatory arts and social action research. Our methodological keynote speaker Helga de Valk (NiDI) highlighted the need for comparative studies and a life course approach to provide better insights into the family dynamics of migrant families.

A number of challenges were also raised. These related to existing data limitations, difficulties in defining families and the challenges of using different datasets at country level and for cross-country studies. In this ‘post-truth’ age it is even more important that our methodological approaches are robust and innovative as scepticism surrounding ‘experts’ presents challenges for future migration research.

On the second day the focus shifted to substantive issues at play in terms of policy and practice and the experiences of migrant and refugee families including those of children and elderly parents.

While the conference had a wider remit than family reunification, this was undoubtedly a major theme. The multitude of legal and policy issues related to families and their mobility were highlighted in relation to family reunification policy at both a European and nation state level.

The legal positions of couples, where one person is an irregular migrant was elaborated by Betty de Hart (University of Amsterdam) and Johnathan Darling(University of Manchester) explained how family life is governed in the UK by the asylum dispersal system.

Sue Lukes (MigrationWork CIC) also outlined the ways child migration has been framed in policy and public discussions in relation to housing. Eleonore Kofman(Middlesex University), the conference keynote speaker for day two, discussed the increasing restrictions on family members’ migration and the implications this has for families. These discussions made it clear that legal and policy restrictions have a profound impact on families, particularly those outside of the nuclear definition of the family.

Indeed another major theme of the conference was the narrow definition of ‘family’ in policy terms which often means adult children and elderly parents are left without support. For instance, elderly care and care by the elderly has become a particularly pressing issue.

Eleonore Kofman (Middlesex University) highlighted that bringing over one’s parents to care for them in old age or to be a support for one’s own child care responsibilities is becoming untenable. Moreover as Chris Phillipson (University of Manchester) and James Nazroo (University of Manchester) discussed, migrants who have grown older in the UK are often experiencing social isolation, particularly since they tend to live in deprived areas and experience poorer health than their White British counterparts.

How families have been used as symbols surrounding migration was another main focus of the conference. Saskia Bonjour pointed out that families are often burdened with representations as regressive and in conflict with so called ‘integration’. This is something Daniela Sime (University of Strathclyde) highlighted in her exploration of the racialisation of Roma Children in Glasgow and Nando Sigona (University of Birmingham) examined how narratives around children come into play in the denaturalisation of asylum seekers crossing the Mediterranean Sea.

Louise Ryan (University of Sheffield) picked up on this tension in her discussion of children and social networks. At a time when the term ‘integration’ has become so symbolically damaged, Ryan’s focus on ‘embeddness’ provided a useful lens through which understandings of migrant families within the UK could potentially be reframed.

The conference also highlighted the lived and affective experience of migration which is perhaps most keenly felt when we think of it in relation to the family. Alice Bloch (University of Manchester) took us through how the second generation often experience the stories and silences of their parents refugee experiences and how these past events echo in family histories.

Melanie Griffiths (University of Bristol) mirrored some of these issues by describing the difficulties precarious male migrants experience in the UK. Anya Ahmed(University of Salford) examined affect from the other side of migration, that of elderly migrants from the UK living in Spain who try to negotiate transnational intergenerational family relationships.

Recurring Themes

A recurrent theme throughout the two days was the disconnect between policies and practices relating to migrants and the experiences of migrant families in Europe. The conference highlighted the tendency of public and policy discourses to view migrants as a monolithic mass of simply economic agents rather than as family and household units.

As the government enters into Brexit negotiations about the rights of movement of EU citizens and settlement in the UK, it is the interests of families that need to be understood and protected. Despite the innovative and exciting research outlined at the conference there is still a lot to learn about the experiences of migrant families across Europe. For this reason, we are developing a European Network examining migration as it relates to families.

A network to understand migrant families

Our aim is to be present throughout the Brexit process and beyond to remind decision makers of the families their choices are affecting. The Network will create a platform to share and critique research, practice and policy across Europe.

Upcoming activities include a planned seminar series to increase our understanding of empirical comparative research on family migration and a special issue on methodological issues in researching migration and the family.

Our overarching objective is to highlight how families are shaped and constructed through policy and practice and reframe the often salient ways migrant families have been understood in relation to diversity, cohesion and the rising tide of nationalism across Europe. To find out more join the network.

GDI at the Development Studies Association Conference

Eleven academics from the Global Development Institute are helping to convene seven panels at the annual DSA conference in September. The 2017 Development Studies Association Conference will be held at the University of Bradford from the 6-8th September and will focus on Sustainability interrogated: societies, growth, and social justice and will feature.

Professor David Hulme, Executive Director of the Global Development Institute, will also deliver the President’s Valedictory lecture. read more…

February research round up

Each month we bring you the latest publications from the researchers at the Global Development Institute.

Books

Kunal Sen has published a new book with Sabyasachi Kar: The Political Economy of India’s Growth Episodes

David Lawson, David Hulme and Lawrence Ado-Kofie have published a new edited volume: What Works for Africa’s Poorest read more…

Gendered Urbanisation and the Paradox of Prosperity: From Feminising to Feminist Cities

By Sally Cawood, PhD researcher at the Global Development Institute

By 2030, it is predicted that nearly five billion (60%) of the world’s population will live in cities[1]. Whilst these spatial shifts are occurring globally, the pace and complexity of urbanisation in the Global South is fundamentally (re)shaping social, economic, political and environmental relationships. Towns and cities are increasingly portrayed as emancipatory spaces that bring ‘prosperity for all’, especially women and girls. Whilst this may be the case for some (due to greater mobility and freedom, earning opportunities and access to services), the reality for many – especially those living in slum settlements – is strikingly different.

On International Women’s Day (8th March 2017), Prof Sylvia Chant shared why a gendered lens is critically important to understand contemporary urban transformation. She outlined three key trends; 1) that women are increasingly the majority population in towns and cities in the Global South; 2) there is a discrepancy between what urbanisation means in principle, and what happens in practice and 3) slums represent spaces where women and girls face interlocking penalties. read more…

LISTEN: Exploring Big Data for Development: An Electricity Sector Case Study from India

Ritam Sengupta, Richard Heeks, Sumandro Chattapadhyay and Christopher Foster recently published a new Working Paper entitled ‘Exploring Big Data for Development: An Electricity Sector Case Study from India’. You can read the paper, and other Development Informatics Working Papers on the GDI website.

Prof Richard Heeks recently presented the working paper as part of a Centre for Development Informatics seminar. You can listen to the presenation in full below. There is also a version which includes the question and answer section available.

read more…

GDI Lecture Series: Gender, Urbanisation and Poverty with Professor Sylvia Chant

On Wednesday, 22 February, Professor Sylvia Chant gave a lecture entitled ‘Gender, Urbanisation and Poverty: Principles, Practice, and the Space of Slums ’. You can listen to the lecture in full or watch the live stream below

Why are right wing Republicans standing up for international aid?

By Professor David Hulme, Executive Director Global Development Institute

The Trump administration looks set to propose “fairly dramatic reductions” to America’s aid programme later this month. This is unsurprising given the extreme nationalism of his “America First” approach, but why are Republican senators like Marco Rubio speaking out?

ODI’s Alex Thier has some interesting thoughts about why many US senators and congressmen will oppose cuts, arguing that ultimately they will make America weaker in the world. read more…

Transforming the role of women in Global Value Chains #IWD2017

This International Women’s Day 2017 the campaign theme is #BeBoldForChange – a call for us to forge a better, gender inclusive working world.

The Global Development Institute’s Professor Stephanie Barrientos has been researching the sustainability of global value chains including cocoa, fresh vegetables, fruit, flowers and garments for over 15 years. Her research played a positive role in addressing global inequalities and supporting initiatives to empower women workers. Some of her recommendations were used as the basis for the Cadbury Cocoa Partnership which later evolved into today’s Cocoa Life scheme.

So why are we looking at Stephanie’s work on International Women’s Day 2017?

We are seeing increasingly large numbers of women drawn into employment in global value chains – compared to more traditional forms of production. It is estimated 70% of world trade now passes through value chains, many led by global retailers. Stephanie’s research highlights the challenges and benefits to women of working in global value chains:

- Women constitute a significant share of the workforce in labour intensive production in global value chains, but are concentrated in precarious and flexible work with poor labour conditions

- At lower value chain tiers many workers’s incomes are below a living wage. Women workers often experience verbal and sexual harassment from male supervisors.

- Downward pressure on costs and increased requirements for flexibility placed on suppliers reinforces precarious working practices.

Quality standards required by buyers can raise demand for more skilled workers, which helps drive improvements in working conditions and rights

Research has shown paid work in global value chains increases women’s economic independence and voice. However, proactive strategies are needed to promote greater gender equality and women’s economic empowerment.

Recently Stephanie gave presentations at SOAS University of London and University of Warwick on ‘Retail Shift: Transforming Work and Gender in Global Value Chains’. She advanced a gendered analysis of global (re)production networks (GrPNs), drawing on global value chain analysis, labour geographies and feminist political economy.

Drawing on case studies on women’s work in cocoa, fruit, flowers and garments, her research shows outcomes for women can be mixed. Those caught in ‘low road’ cheap labour value chains experience poor conditions and low wages. Those engaged in ‘high road’ value chains requiring greater skill and productivity are more likely to enjoy better conditions and rights.

Stephanie’s research provides insights into social upgrading and downgrading (better or worse conditions and rights), and how these play out for different workers. It examines to what extent engaging in global value chains reinforces gender inequalities or opens up channels for promoting gender equality and women’s economic empowerment.

Social upgrading for women workers can occur under some circumstances, but it is far from automatic:

- Civil society campaigns can help to leverage improvements in working conditions and gender equality. This occurred in the Kenyan flower industry over the past decade.

- Company moves to increase quality and productivity, and rising concerns over the future resilience of their supply chains can help drive improvements. This is now occurring in cocoa-chocolate value chains following industry predictions of a million ton cocoa shortage by 2020.

- Government regulation needs to be more proactive in ensuring better labour conditions and rights for all workers (permanent and casual). This must include ensuring workers earn a living wage and smallholder farmers a living income.

In conclusion Stephanie argues that changing retail procurement practices and changing patterns of consumption in developed and emerging economies are transforming gendered patterns of work. Downward pressure on costs, quality standards, civil society campaigns and increased requirements for skilled labour are resulting in complex gender dynamics.

Effective governance and proactive strategies by all actors (public, private and social), is critical to promoting greater gender equality in global retail value chains and supporting women’s economic empowerment.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

The race for Sustainable Development by 2030: Some baby-steps towards leaving no one behind

By Fortunate Machingura, a Global Challenges Research Fund Postdoctoral Fellow at the Global Development Institute, University of Manchester. Fortunate holds a PhD in Development Policy and Management from the University of Manchester

By Fortunate Machingura, a Global Challenges Research Fund Postdoctoral Fellow at the Global Development Institute, University of Manchester. Fortunate holds a PhD in Development Policy and Management from the University of Manchester

The aphorism that the populations furthest behind should be reached and no one should be left behind continues to consume the development world. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have galvanised thinking about how to leave no-one behind, based on optimism around the world’s ability to cooperate and govern for sustainability towards ending poverty, deprivation, and inequality for all. Questions of who these populations are, where they live and what kinds of inequalities they experience are critical.

Some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have taken the leave no-one behind mantra to heart; policymakers, NGOs, the private sector, donors and other decision-making stakeholders, are making frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment of populations and social groups that are “behind”. For example:

- South Africa’s National Development Plan (NDP) 2030 speaks to the SDGs and aims to eliminate poverty, create jobs and reduce inequality for all, by 2030.

- In Ghana, the SDGs form an integral part of its 2014-2017 national development plan (Shared Growth and Development Agenda) demonstrating initial steps towards localising the SDGs.

- Zimbabwe has assigned each of the 17 SDGs into (sub)clusters of the current National Development Plan (Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Socio-Economic Transformation 2013-2018) ahead of the next Development plan post-2018.

At the project and program level, improved methods and more rigorous approaches to evaluation of development outcomes have led to a massive effort to ensure that resources are mobilised and effort is deployed to the best effect for poorer quintiles of the population who need these resources the most. read more…

An Emerging Digital Development Paradigm?

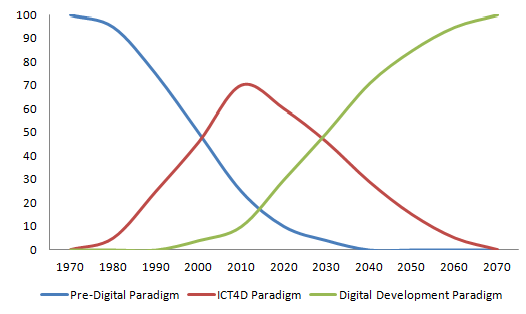

Taking a longer-term view, the relationship between digital ICTs and international development can be divided into three paradigms – “pre-digital”, “ICT4D”, and “digital development” – that rise and fall over time (see Figure below).

The pre-digital paradigm dominated from the mid-1940s to mid-1990s, and conceptualised a separation between digital ICTs and development [1]. During this period, digital ICTs were increasingly available but they were initially ignored by the development mainstream. When, later, digital technologies began to diffuse into developing countries, they were still isolated from the development mainstream. ICTs were used to support the internal processes of large public and private organisations, or to create elite IT sector jobs in a few countries. But they did not touch the lives of the great majority of those living in the global South.

The ICT4D paradigm has emerged since the mid-1990s, and conceptualised digital ICTs as a useful tool for development [2]. The paradigm arose because of the rough synchrony between general availability of the Internet – a tool in search of purposes, and the Millennium Development Goals – a purpose in search of tools. ICTs were initially idolised as the tool for delivery of development but later began to be integrated more into development plans and projects as a tool for delivery of development.

The isolationism of the pre-digital paradigm remains present: we still find policy content and policy structures that segregate ICTs. But integrationism is progressing, mainstreaming ICTs as a tool to achieve the various development goals. From the development side, we see this expressed in national policy portfolios, in Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers, in UN Development Assistance Frameworks. From the ICT side, we see this expressed in national ICT policies and World Summit on the Information Society action lines.

The ICT4D paradigm is currently dominant and will be for some years to come. Yet just at the moment when it is starting to be widely adopted within national and international development systems, a new form is hoving into view: a digital development paradigm which conceptualises ICT not as one tool among many that enables particular aspects of development, but as the platform that increasingly mediates development.

This is the subject of a Development Informatics working paper: “Examining “Digital Development”: The Shape of Things to Come?”, and will be the topic for future blog entries.

[1] Heeks, R. (2009) The ICT4D 2.0 Manifesto: Where Next for ICTs and International Development?, Development Informatics Working Paper no.42, IDPM, University of Manchester, UK

[2] ibid.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.