January research round up

Each month we bring you the latest publications from the researchers at the Global Development Institute.

Books

Justice Nyigmah Bawole, Farhad Hossain, Asad K. Ghalib, Christopher J. Rees and Aminu Mamman edited a new book, Development Management in developing and transitional countries: Theory and practice, which is available through Routledge press.

The Politics of Inclusive Development by Samuel Hickey, Kunal Sen and Badru Bukenya has been made Open Access.

Journal Articles

Uma Kothari and Alex Arnall published Contestation over an island imaginary landscape: The management and maintenance of touristic nature in Environment and Planning A.

Panom Gunawong and Pin Gao co-wrote an article, Understanding e-government failure in the developing country context: a process-oriented study, which has just been published in Information Technology for Development.

GDI Working papers

Judith Krauss published GDI working paper entitled What is sustainable cocoa? Constellations of commercial, socioeconomic and environmental priorities associated with a polysemic concept.

Olabimtan Adebowale and Ralitza Dimova co-wrote a working paper, Does access to formal finance matter for welfare and inequality? Micro level evidence from Nigeria.

Other working papers

Rebecca Martin & Richard Duncombe wrote a paper for the Development Informatics Working Paper series, Best Practice for Implementing Mobile Finance in Low-Income Communities

Students arrive in Cape Town for #ICT4D fieldwork

By Caroline Boyd, Addressing Global Inequalities Campaign Manager

As the local song goes, “Welcome to Cape Town, let’s see you smiling!”

Cape Town warmly welcomed 70 of our Development Informatics students last week and has been the home to both them and to me for the last five days. With another five days to go on our #GDIFieldwork experience here, this half way point seems a good time to reflect on the experience so far.

Dr Jaco Renken, Lecturer in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) for Development, has pulled together a wide-ranging and inspirational fieldwork trip which has so far shown students at first hand how ICT, data management and strong leadership within organisational management can work across settings ranging from Cape Town’s Teraco Data Centre, Cape Town City Council and Khayelitsha Hospital.

All nestled within clear sight of Table Mountain, these organisations and the professionals, communities and townships are very diverse and have been making a real impact on our students as they consider their future studies and working lives.

Chatting with students whilst also out here experiencing Cape Town as a first timer, I’ve heard how impressed they are by the difference excellent digitisation and data management within the hospital we visited seems to have had in impacting lives for the better and aiding development work.

Fieldwork is an important time in every student and researcher’s life. It’s about reigniting passions, discovering new ones and – on this particular trip – realising each student’s own possibilities by pushing personal boundaries to new places.

Fieldwork is an important time in every student and researcher’s life. It’s about reigniting passions, discovering new ones and – on this particular trip – realising each student’s own possibilities by pushing personal boundaries to new places.

Not wanting to miss out on the excitement, I have been discovering my own potential too as we all joined forces together for a hot, steep, achey but awe-inspiring climb down the mighty Table Mountain yesterday. With all students down in just over 2 hours and having acquired “Table Mountain legs” (a term affectionately created by previous GDI walkers who experienced a leg-to-jelly effect post climb!), it was certainly a personal highlight and a significant moment in life for many who had never attempted such a challenge before.

So let’s see what our ICT visits in Cape Town brings tomorrow. But if we can climb down Table Mountain, surely we can keep learning and innovating new ways to address global inequalities by using information technologies to bring about positive change to the lives of those in this city and far beyond.

See more pictures and updates on #GDIFieldwork on Twitter

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

GDI Lecture Series

The Global Development Institute Lecture Series brings together scholars involved in cutting edge research on international development. It aims to facilitate dialogue and discussion, providing a space for leading development thinkers to share their latest research ideas.

The Lecture Series will return on Wednesday, 8 February with Professor Julien Harou from the Engineering Department at The University of Manchester on developing water-energy-food systems.

Lectures will be held in Theatre B, Roscoe Building from 5.00 – 6.30pm BST. read more…

Alumni profile: Gale Raj-Reichert

Gale holds a PhD in International Development Policy and Management from GDI. After completing a British Academy Post-Doctoral Fellowship with us, she joined Queen Mary University of London as a Lecturer in Economic Geography.

Gale holds a PhD in International Development Policy and Management from GDI. After completing a British Academy Post-Doctoral Fellowship with us, she joined Queen Mary University of London as a Lecturer in Economic Geography.

Why did you choose GDI for your PhD?

After earning my Bachelor’s at the University of Michigan in Environmental Science and Policy, I went to work at the environment programme at the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation. I worked on international issues, including trade and finance, which opened a whole new world for me, and lead to an interest in globalisation and developing countries. I did my Master’s of Public Policy also at the University of Michigan in International Economic Policy, and decided that I wanted to continue to work in international contexts.

In 2003 I went to work at an inter-governmental organisation called the South Centre, in Geneva, Switzerland. South Centre is made up of developing country governments, created as a think tank to promote their interests and pro-poor development. Most of the work during my three years there focused on assisting developing countries in their negotiations in the World Trade Organisation, working one-on-one with delegates.

Eventually, I wanted to be able to write my own papers on development issues and decided to pursue research, and came to do a PhD at the Global Development Institute. I chose GDI (then IDPM) for many reasons, but one was because it was interdisciplinary, housed in the School of Environment, Education and Development: although I wanted to focus on developing countries and trade issues, I was also interested in global environmental justice. GDI was able to marry all of those interests, though the PhD took a slightly different turn in the end.

My PhD was followed by two lectureships and I have just finished a three-year British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship at GDI. read more…

Countering “divide and conquer” to build a human economy for all

Have we all been “divided and conquered” by the super-rich? Political divides and polarisation were highly apparent in the UK and the US in 2016, and are highly prominent elsewhere in Europe. Votes for Brexit and Donald Trump have brought renewed attention to major cleavages within society – along economic, social, cultural, urban/rural lines. This has fostered disagreement and tensions amongst people who encounter each other in their daily lives, distracting attention from the almost mythical super-rich, with their almost impossible-to-relate-to amount of wealth. While such divides amongst the 99% (or even 99.9%) have grown and need to be addressed, stealthily the global super-rich seem to get wealthier and wealthier.

Extreme inequalities: a timely reminder

Oxfam’s flagship annual report of global inequalities, timed to coincide with the Davos World Economic Forum meeting reveals its most shocking-yet figures in terms of global wealth inequality – the combined wealth of the wealthiest 8 people (all men) on the planet is equivalent to that of the bottom 50% of the global population. The report valuably refocuses attention on where the starkest inequalities lie – between the super-rich and the rest.

The report contains a range of staggering statistics on various inequalities. A few that stand-out include:

- The World’s richest 1% own more than the other 99% combined

- While two buses were needed a couple of years ago to fit those people who own more than the poorest half of humanity, now only a large golf buggy is needed

- Between 1988 and 2011 the incomes of the poorest 10% increased by just $65, while the incomes of the richest 1 percent grew by $11,800 – 182 times as much.

- A FTSE-100 CEO earns as much in a year as 10,000 people in working in garment factories in Bangladesh.

- On current trends, it will take 170 years for women to be paid the same as men.

Following on from 2016’s “An economy for the 1%”, Oxfam’s 2017 report “An economy for the 99%” – rather than increasing divisions – seeks to lay out a positive vision of a “human economy” that could work for all.

Oxfam’s wealth statistics and interpretations are often critiqued. Critics like to point out that wealth is not income or consumption. For example, someone who just graduated from Harvard Medical School could be in the lowest decile of global wealth, yet this could be a very short-term position as they are likely to be very high up the income distribution. Americans with a lot of debt, but potentially high income and consumption, can then be found amongst the lowest 10% of global wealth.

A box in the report (p. 11) on the wealth inequality calculations addresses these critiques and clearly explains the methodology (based on data from Credit Suisse and Forbes billionaires list).

A global challenge

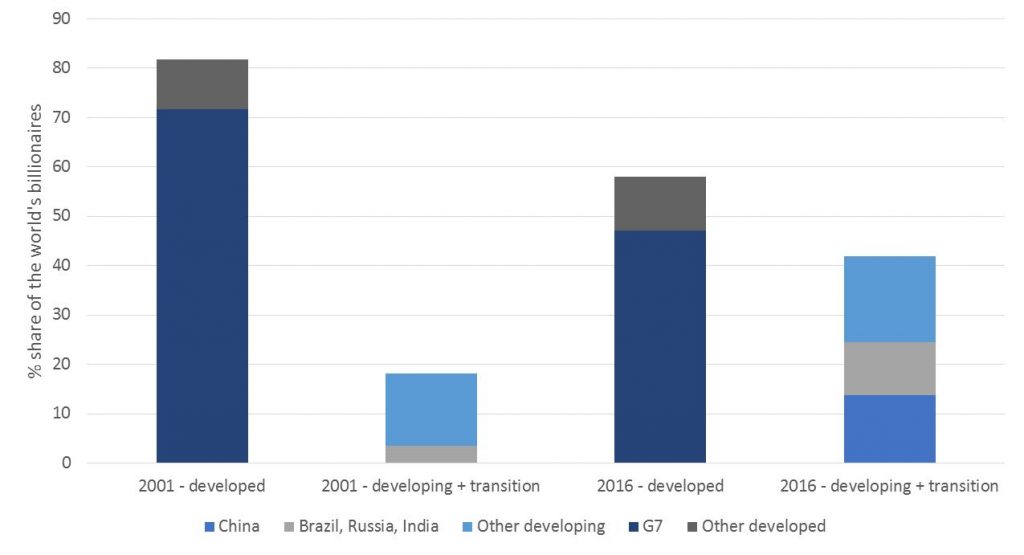

One wealth statistic Oxfam’s report doesn’t mention, but which the Forbes billionaire’s list also shows, is the shifting geographical composition of billionaires – a rapidly growing portion are from developing countries. The figure below, from my ongoing research with David Hulme, on contemporary global development, depicts this growing share.

Source: Horner and Hulme (forthcoming).

The number of U$ billionaires for the world has more than trebled from 538 to 1,810 from 2001-2016, yet the increase has disproportionately been in particular developing countries. While the number of billionaires as a whole has increased almost two and a half times in countries that fall into the UN’s classification of “developed”, it has increased almost 7.5 times for developing countries. In that 15-year period, the number of billionaires has increased in China from 1 to 251 (251 times increase), and India from 4 to 84 (21 times increase). In the “transition” economy of Russia, the number has increased from 8 to 77 (a 9.6 times increase).

This shows the growing extent of a significant disconnect between the super-wealthy and the societies in which they come from. Moreover, despite a slightly more even spread of aggregate incomes, jobs, prosperity, across countries – what some are calling a “great convergence”, much of this benefit is accrued by a small minority of the population. Extreme inequalities are thus a global problem – within and across societies.

Oxfam has previously (and already this year) been accused of mis-directing attention from the economic bottom-half of the world’s population to the global 1%. The 2017 report does note progress in terms of reduced numbers living in extreme poverty by official measures, especially driven by China and India. It could also be added that some research by leading inequality researchers such as Branko Milanovic and Francois Bourguignon – albeit using measures which are less attuned to capturing the extremes at the high end of the scale – finds somewhat of a reduction in global income inequality across individuals has taken place in recent years (driven by growing incomes in China and India particularly). Such research still points to vast income inequalities. Oxfam suggests that without such extreme concentration of wealth, much more progress could have been made in addressing extreme poverty.

Rather than mis-directing attention, Oxfam’s report is a shocking reminder of, and valuable signal to, where the starkest inequalities lie: the divide between the 1% (and even the upper fractions of it) and the 99%. Rather than income streams relating directly to how hard or well people work at a particular occupation, as Thomas Piketty as shown, wealth has growing significance in the global economy. As well as the headline wealth statistic, the Oxfam report presents a shocking collection of facts about other extreme inequalities related to wages, gender etc.

Development “goods” – wealth and income being key – are overwhelmingly accrued by a small portion of people. Development “bads” – as Oxfam’s work on carbon inequalities has shown – are also contributed by those same people.

While super-rich individuals and corporations are begged to come to different countries (the report notes various such incentives), refugees are often forcibly kept out and even blamed for increasing inequality.

Differences among the 99% have been invoked and publicised fostering battles amongst the vast majority. In the US, this week a President who has sought to invoke addressing those “left behind” will be inaugurated. Without question, he will continue to divide the 99% and overlook the 1% (and its extreme upper end) which he and his “billionaires and mere millionaires” cabinet are part of.

Reformed international cooperation for a human economy

In line with attempting to construct a positive vision of an “economy for the 99%”, Oxfam make a number of valuable suggestions, including:

- International cooperation to avoid tax dodging

- Wealth taxes to create funds for healthcare, education and job creation

- Action to encourage companies to benefit workforce and society, as well as executives and shareholders

- Tackling educational barriers and burden of unpaid work for women

To make such suggestions work will require a countering of the “divide and conquer” by the super-rich, with a mobilisation within and across countries.

Most countries have sufficient resources domestically for there to be considerable scope within countries to address inequalities. While this has long been the case in the Global North, it is increasingly the case in the Global South. One recent analysis suggests that more than 75% of global poverty at lower lines could be eliminated via domestic redistribution funded by new taxation and reallocation of public spending.

Yet, international coordination is vital too. Oxfam suggests “governments must cooperate” and this point couldn’t be amplified enough. To be clear, much previous international cooperation has been mis-directed in the interests of the super-rich- making things easier for certain companies, but not for many people or for many small businesses. Rather than an abandonment of international cooperation – or a retreat from globalisation takes which could equally be skewed to restricting certain mobilities and favouring the highly mobile super-rich – a reformulation is needed. Action on corporation tax and a wealth tax can only fully work with such international coordination.

Surely nearly all of us can agree that such extreme inequalities are unwarranted and unjust? To move away from being “divided and conquered” by the super-wealthy, a much more unified approach within and across countries is needed. Oxfam’s 2017 report is a timely reminder of that.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

#DevTrends2017: Why Donald Trump Will Make China Great

David Hulme continues our series on the big development trends to look out for in 2017

Donald Trump has promised to make the USA “great” again. A central element of this strategy seems to be protectionism but, I think even more important will be his stance on climate change. If he persists with climate change denial – which seems likely with the environmental team he has pulled together – then I believe this will accelerate the rise of China and the decline of the USA. If Trump turns his back on the US/China (Obama/Jinping) joint leadership for tackling climate change then I believe China will take on global leadership solo. With its greenhouse emissions beginning to plateau out sooner than expected (China has moved into renewables at an unbelievable speed) then China could work with the Vulnerable Countries Forum, more than half of the UN’s member states to “save the world”. I am certainly revising my opinions on the multi-polar world we live in…I am warming to China and cooling towards the US…are you?

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Difficult news for Fairtrade chocolate – what does this mean for cocoa sustainability and Fairtrade?

By Dr Judith Krauss, Post-doctoral Associate, Global Development Institute

Cadbury’s decision to shift its sustainability focus away from Fairtrade towards its parent-company’s ‘Cocoa Life’ scheme has sent shivers down the spine of many Fairtrade supporters. The BBC (among others) has asked whether this may mean the end for Fairtrade. While it is certainly difficult news, I would argue that firstly, this is not an entirely new development, and secondly, we have to further investigate the implications of the move for cocoa sustainability and for Fairtrade, as they will only become clear over time and are subject to on-going negotiation. read more…

In remembrance of Sir Tony Atkinson – a leader in inequality research and thinking

The Global Development Institute was saddened to hear of the recent death of Sir Tony Atkinson – a long-standing leader on inequality research including the recently published ‘Inequality: What is to be done?’

At a time when of a growing consensus identifying the ills of inequality, Sir Tony stepped into the void to discuss the type and scale of policy changes required to reverse the trends.

We were proud to call Tony our friend when he visited us in 2015 to give a wonderful lecture at the University whilst ill at that time. He was usually the greatest intellect in the room but he never asserted that superiority and he was always listening carefully to what others had to say. A great intellect but a very modest human being.

Tony will continue to inspire us as we address global inequalities and we send our thoughts to his family, friends and loved ones.

Take a look here at Professor David Hulme’s blog post following Tony’s visit to the University in June 2015.

#DevTrends2017: Will the gendered impacts of climate change be taken seriously?

Joanne Jordan continues our series on the big development trends to look out for in 2017

In 2016 the main focus around climate change issues was on ratifying and maintaining international momentum after the Paris Agreement. In the future I think we need to see much more attention given to the gendered impacts of climate change and women’s role as agents of change. There were some promising moves at COP 22 in Marrakesh, but there’s much more work to do.

We know that women tend to be disproportionately affected by climate change, often constrained by their responsibilities for children and the elderly during and after a climate event, and are more likely to die and or be exposed to sexual and physical violence. Despite this, there is limited empirical and context specific case studies that examine the gendered experiences of women to climate change. read more…

#DevTrends2017: Can adaptive management save DFID?

Pablo Yanguas continues our series looking at the big development trends to look out for in 2017

These are difficult times for the foreign aid system. While budgets may still be growing in countries like the UK, the reality of aid is one of dire challenges on two fronts.

At home in donor countries, fiscal hawks keep demanding total value-for-money for every aid pound spent, while opportunistic conservatives quietly redirect overseas development assistance towards the private sector. Away in recipient countries, the rise of South-South cooperation, billionaire philanthropists, and increased access to financial markets is crowding out foreign aid from the low-hanging fruit of high-expense, high-visibility projects like hospitals and irrigation. read more…