Ailbhe Treacy, MSc International Development: Development Management

Why do development charities in the UK close? How do these closures impact the wider sector? My MSc Dissertation aimed to answer these important questions by examining UK development NGO closures between 2016 and 2021. The findings suggest that smaller and younger NGOs, faced with a changing donor landscape and a lack of diversified funds, are disproportionately impacted by dissolutions.

Which NGOs are most likely to face closure?

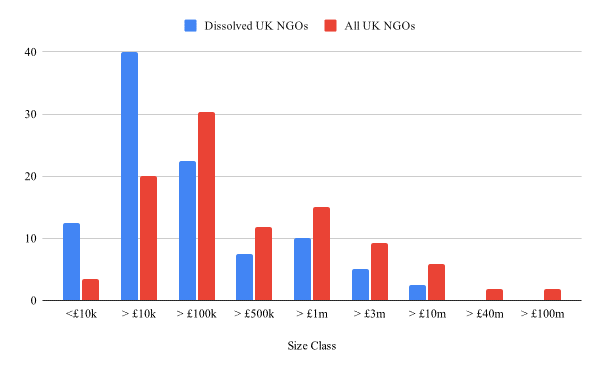

Based on an existing database of 898 UK development NGOs, my research examined the characteristics of dissolved organisations in comparison to the wider population of NGOs. By dividing charities into size classes based on their average annual expenditure, the results show that NGOs with lower expenditures are overrepresented within the cohort of dissolved organisations, a finding consistent with previous research suggesting that income inequality between NGOs is on the rise.

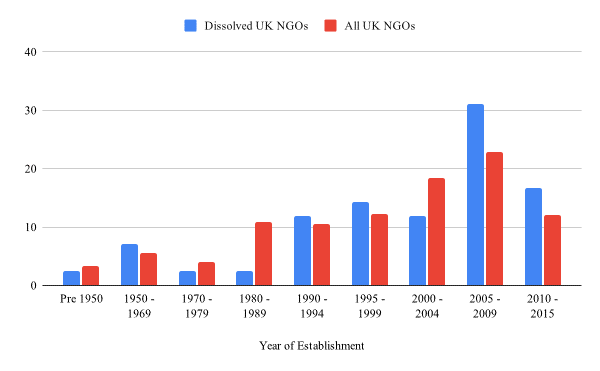

NGOs with fewer years of service are also overrepresented amongst dissolved NGOs, with those established between 2005 and 2015 most likely to face closure.

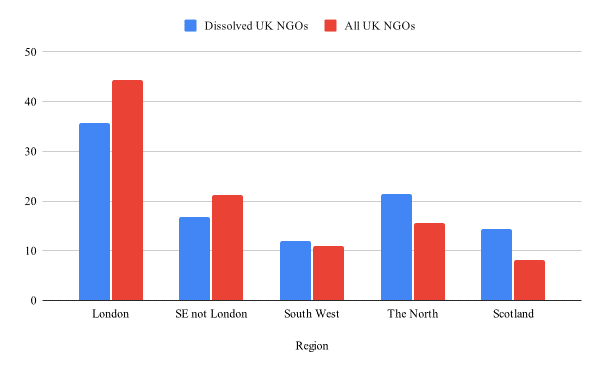

Finally, regional disparities impact NGO closures, with London and the wider South-East underrepresented within the cohort of dissolved NGOs. This finding builds on previous research suggesting that organisations in these regions benefit from proximity to powerful elites and government officials.

Figure 3: NGOs in London and the wider South-East were least likely to face closure between 2016 and 2021.

Why do NGOs close?

Out of the 41 NGOs that closed down in the UK from 2016 to 2021, 21 provided publicly accessible narratives surrounding their closure.

Two-thirds of the organisations that I examined cited financial difficulties as their reason for closing. In 13 out of 14 cases, NGOs faced dissolution after losing a single source of funding. Although little is known about fund diversification in relation to development NGOs, some research suggests that its impact on organisational survival is limited.

The majority of NGOs closing due to financial instability have relied primarily on public giving. For some, costly means of raising donations resulted in gross mismanagement of funds. In particular, 4 NGOs reported spending the majority of their funds on direct mailings, a once popular means of fundraising that has previously attracted scrutiny from journalists and the Charity Commission for England and Wales. In the case of one NGO, just 7% of funds were directed towards charitable activities, with the rest being spent on overheads.

Among NGOs primarily funded through government funding, Brexit and changes to DFID funding priorities have been cited as catalysts for closure. In the case of The International NGO Safety Organisation, which spent £15.4 million in 2017/18, the Brexit referendum prompted a relocation to the Netherlands in order to retain European Commission funding.

Although the topic of NGO closures suggests a focus on organisational failure, my research uncovered several success stories. In 4 cases, NGOs have been removed from charity databases as a result of Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A). NGO M&A is an underresearched area of development. However, early research suggests that M&A, when pursued proactively, can positively benefit scale of delivery, quality of outcomes and attractiveness to donors. This is reflected in the findings of my dissertation, with 3 NGOs reporting positive outcomes in the years following M&A.

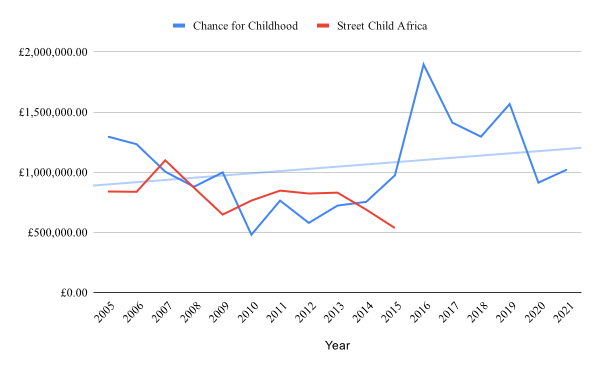

This is illustrated in the case of Street Child Africa, who in 2015 ‘undertook a review of small, like-minded charities working in similar fields with similar programmes to provide stronger, more holistic support’ for its beneficiaries. In 2016, Street Child Africa successfully merged with Chance for Childhood, who reported lower overheads and increased charitable spend as a result.

Figure 4 shows the incomes of both SCA and Chance for Childhood before and after the merger. Street Child Africa saw an overall decline in income in the years before its decision to become part of Chance for Childhood. Despite drops in income associated with the 2008 financial crash and COVID-19, the trendline in Figure 4 shows a modest increase in Chance for Childhood’s income following the merger. Trustees reported in 2022 that Chance for Childhood was on the ‘road to recovery after the negative impact of COVID-19 on fundraising’.

Figure 4: Chance for Childhood saw an increase in income following its merger with Street Child Africa, despite external shocks.

Much has been written about NGOs’ attempts to avoid organisational death by expanding or changing their charitable aims. In contrast, my research uncovered 2 cases in which NGOs reported successfully achieving their missions, prompting voluntary closure. Both organisations, which focused on water, sanitation and hygiene, found that a cooperative approach and clearly defined aims allowed for the accomplishment of their missions.

As Covid-19 and cuts to UK foreign aid continue to impact NGO finances, the study of NGO closures may be more important than ever. In 2020, former Oxfam International head of strategy, Barney Tallack, stated that northern INGOs faced three options in response to mounting threats to survival: transform, die well or die badly. While understanding the characteristics of dissolved NGOs can help us to identify the organisations most at risk of dying badly, insight into the narratives surrounding NGO closures may guide their path to transformation.

Photo by Aaron Doucett on Unsplash

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.