Adriana Kemp, Professor of Sociology, Tel-Aviv University and Tanja Müller, Professor of Political Sociology, Global Development Institute

If citizenship is about shaping cities and urban spaces at the same time shape migrants, the question becomes how the different life-worlds of migrants and cities come together. Cities are increasingly seen as models of complexity, all the more so as we seem to live in multiple ways in times of crises. At the same time, city planning and the social and economic dimensions of crises hardly ever seem to connect. Cities do not seem to be built for the people living in them and their needs – but to live up to some planning ideals or, even more mundane, to the profit strategies of entrepreneurs and global investors.

This happens at a time when the social sciences have seen a number of visual turns and de-turns – but the call for visual literacy, issued as far back as the times of Du Bois, has too often remained unheard. This leaves us with the question of how critical visualisation is possible and how the co-production activities we have seen in other spheres of the social sciences, in relation to cities very prominently, for example, in the work and activism by Shack-Dwellers-International (SDI) and academics combined, can become embedded into urban planning and regeneration processes. Arguably, what is needed is a form of regeneration that does not result in gentrification and the displacement of long-term residents from urban spaces but gives residents the tools to shape the urban areas they occupy themselves.

Two interesting approaches can be observed in Haifa: The Smart Social Strategy Lab based at the Haifa Technion; and the investments of impact entrepreneurs in a neighbourhood with a substantial migrant population.

The Smart Social Strategy Lab aims to bring together the worlds of planning and social, and in particular, to communicate social issues into the concrete context of planning processes. It does so via the whole toolbox of visual representations. An important tool here is the digital twin – a fuzzy concept from product development and machine science that aims to provide the digital representation of a real-world object. Here, the digital twin of a city or part of a city aims to represent layers of social knowledge collected with the active participation of the neighbourhood. It aims to translate surveys, observations, and ethnographies into an advanced GIS model.

This is an impressive undertaking, and one can see the potential for co-production of knowledge with residents and also the potential, as one digs deeper and deeper, to apply a historical lens to urban insecurities. Visualisation can be computer-based and highly sophisticated, but one can also simply draw lines on a map, literally.

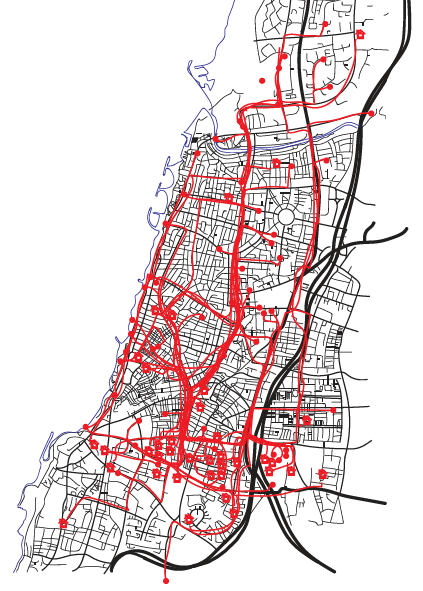

The map is the virtual representation of various spatial movements of migrants in parts of Tel Aviv, combining journeys to work, places migrants like to hang out, and those migrants avoid for fear of police spot checks. Layering up multiple forms of movement on a single map allows plastic and graphic artist Roni Mero to disclose how embodied forms of belonging and non-belonging co-exist in ways that escape official cartographies of migration.

So far, so good. But as with all social science, ethical and power dimensions remain. In the example here, one could ask if making certain locations visible puts those who frequent or avoid them in danger. More generally, as with any data collected on ever larger scales and fed into digital systems for analysis and planning, with the best of intentions, questions about data ownership and who has the power to use and act upon that data remain. While it is an impressive tool to uncover hidden layers in the urban fabric and ideally feed those into (future) planning processes, the need for constant critical interrogation is equally paramount.

A different way to engage and bring social issues into urban infrastructures exists through the engagement of social entrepreneurs. Here the focus is not on urban regeneration as gentrification but on re-creating communal lifestyles in the city through social projects that inspire collaboration, creativity and residents’ participation. One such entrepreneurial initiative in Haifa is making housing that has fallen into disrepair liveable again. ALEF, the organisation for refugees in Haifa, profits from such activities. It is located in a neighbourhood where a group of social impact entrepreneurs has bought a number of houses, and inhabitants pay low rents in exchange for upkeep and renovation activities, or cultural and other offers to the wider neighbourhood.

The top picture is part of the herb garden and communal space that ALEF uses in a gap between some of these houses. For now, the model holds, but reportedly some investors in the consortium have other ideas for the future.

This casts doubt on the ability to buffer socially driven entrepreneurship from for-profit driven initiatives, that is, from “business as usual”. Time will tell if a form of gentrification that displaces many of the people who now live here, including those who have shown participatory and community-driven entrepreneurial skills, may be coming after all.

The work by Roni Mero introduced above is from a study that aims to review the representation of Tel Aviv’s public realm from the point of view of African workers, mainly from West-Africa, who live and work in Tel Aviv. It does so through mapping and categorising procedures, producing a ‘visual reframing’ of the spatial politics of the city – and in doing so acting as a witness to the way the workers maintain their community.

This is the 2nd blog in a series of blogs related to the University of Manchester-University of Tel Aviv partnership project: Inscribing mobile lives into the urban peripheries of global displacement, led by Prof Adriana Kemp and Prof Tanja R. Müller. The series is based on a visit by the Manchester team to Tel Aviv and Haifa in May 2022.

- Top image: Tanja Müller