Keisha Maloney, MSc Global Urban Development and Planning

Once notorious for violence, cartels and drug trafficking, the city of Medellín in Colombia is increasingly becoming known for its transformation not only to peace – but prosperity. Like cities all around the world, Medellín has seen a dramatic increase in its population in the last few decades, exacerbating urban inequality. During the 1970s Medellín was Colombia’s industrial hub, mainly producing textiles. When civil conflict broke out a few years later, rural to urban migration rapidly increased. The housing market was incapable of keeping up with the steady flow of migrants, causing housing prices to increase, and forcing rural, poor migrants to construct homes along the unstable, steep mountainsides that frame Medellín. When Pablo Escobar’s drug cartel gained influence across Colombia, Medellín and its informal settlements became the main theatre for Escobar’s violence. Promising young men riches and status, the hillside comunas became engulfed in extreme violence, poverty, and became inaccessible to police and government officials who feared they would lose their lives upon entering a comuna and crossing an “invisible border” that divided one gang from another.

Most critical to this story is the inability of officials to access comunas which worked to exacerbate urban inequality, as living standards and formal connections to public services were limited. When Escobar was murdered in 1993, and the violence began to deplete, uniquely, the city and its elites decided that they owed the urban poor a great social debt, and that they would focus on redeveloping the city with their needs prioritized.

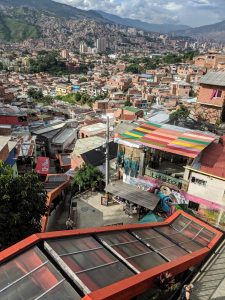

This past June, I travelled to Medellín, Colombia to participate in the Urban Transformation in Colombia program, organized by Red Tree Study, and led by the architecture department at the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana. This was made possible with funding from the SEED Student Research fund here at The University of Manchester. Over two weeks, we attended daily lectures on a range of issues and transformations occurring in the city, with topics covering history, social housing, transportation, and environmental sustainability. In the afternoons we visited the projects we had discussed that morning, seeing the transformation for ourselves. It was fantastic to see these projects in action, as back at class in Manchester we had discussed the Escaleras Electricas, the numerous libraries in informal settlements, and the Metrocable system. Not only was it clear that the lives of informal dwellers had improved dramatically as the city became more accessible – physically and symbolically – but our discussions began to reveal that there were two sides to the ‘Medellín Miracle’.

In constructing pubic community centers and the Metrocable system, many families were displaced from their homes. As many migrants had come from rural areas, where they grew their own food and lived in single-family style homes, the relocation was often disruptive and traumatic. A community leader I spoke with had been relocated from her comuna to social housing towers on the opposite side of the city. When she moved with her family, there were no shops, community centers, government offices, and no job opportunities. The government had chosen to construct a series of buildings on vacant land that had limited access to the city, and no social or cultural networks. Beyond this, the government had not established rubbish collection – leaving the residents living among their trash for years, with some paying third party suppliers to dispose of the rubbish for them.

Most problematic with the relocation process was the disruption of cultural behaviours. While living in the comunas families had allocated space – albeit limited – for growing crops. Now, living in high towers this was not possible. Further, a community member told me that their culture is to be loud, and Colombians are proud that they express themselves through dance. Living in close quarters, with thin walls has created conflict in the hallways as frustrations over noise and minimal space rise. The community member told me that this has reignited violence within the social housing buildings.

Poverty, depression, and a lower quality of life have inflicted the relocated residents, while improved access to the city and community centers have been provided to their old neighbours. How can we measure the tradeoff between providing access to the city for some, and reducing the quality of life for others? Must it be the case that improving the urban form will cause detriment to some? While Medellín provides an exemplary case for finding peace and prosperity among divided groups, for some their methods have proven to be harmful. This raises questions about the sustainability of the projects that Medellín has come to be known for, and the value in exporting them.

The Urban Transformation in Colombia program was an incredible learning experience, each day packed with classes, workshops, site visits, interview opportunities with community leaders, as well as opportunities to learn about the local culture – luckily for us, the Copa America football series was on. While the Medellín Miracle did not prove to be as miraculous as I had imagined, it ignited critical thinking about how we incorporate marginalized groups into the city after violence and exclusion. Medellín has made significant strides, but there are always ways to improve. The case presented here encourages us as students and academics to look beyond what we may be taught in a classroom and continue to question “silver-bullet” solutions to the critical problems facing our world.

This research trip was made possible by the SEED Student Research fund.