By Richard Heeks

(First posted on the ICTs for Development Blog)

Development studies has long grappled with the pressing realities of global inequality, poverty, conflict, and environmental degradation. As a field rooted in critical inquiry, it often focuses on diagnosing systemic problems and challenging dominant power structures.

But what if development studies could also make more space for the affirmative? What if it cultivated a deeper orientation toward hope, creativity, and transformation?

This is the promise of positive development studies: a complementary approach that doesn’t ignore structural critique but insists on also exploring what works, what inspires, and what uplifts.

There would be some parallels with the emergence of positive psychology in the late 1990s, with its focus on well-being, strengths and human flourishing. But positive development studies would not be a naive celebration of “progress” or a retreat into technocratic optimism. Rather, it would be an intentional shift toward identifying and amplifying stories, practices, and models that generate meaningful, sustainable, and just change. It would mean asking not only what is wrong? but also what is right—and how can it be strengthened, shared, or scaled?

At its core, this approach involves rebalancing the epistemological stance of development research. Too often, critical scholarship can dwell on what sociologist Hartmut Rosa calls “diagnoses of alienation”. These are valuable in exposing harm, but sometimes paralysing in effect. A positive lens, by contrast, would foreground resonance: connections between people, nature, and institutions that feel responsive, empowering, and life-enhancing.

Positive Development Studies in Practice

In practice, positive development studies might involve more case studies of grassroots innovation, cooperative economies, and regenerative ecologies. It could mean deep listening to community aspirations, not just needs. It would draw methodological inspiration from appreciative inquiry, participatory action research, and ethnographies of thriving.

Potential examples of this from recent research at the Global Development Institute, University of Manchester include:

- Data-powered positive deviance: analysing new datasets to identify those that outperform their peers in various fields of development, and seeking to scale out their practices and behaviours

- ICT4D champions: understanding the core orientations towards results, relationships and resources that guide those individuals who make a decisive contribution the progress of information-and-communication-technology-for-development initiatives

- Pockets of effectiveness: analysing the emergence and sustainability of those public organisations that function effectively in providing public goods and services, despite operating in an environment where effective public service delivery is not the norm

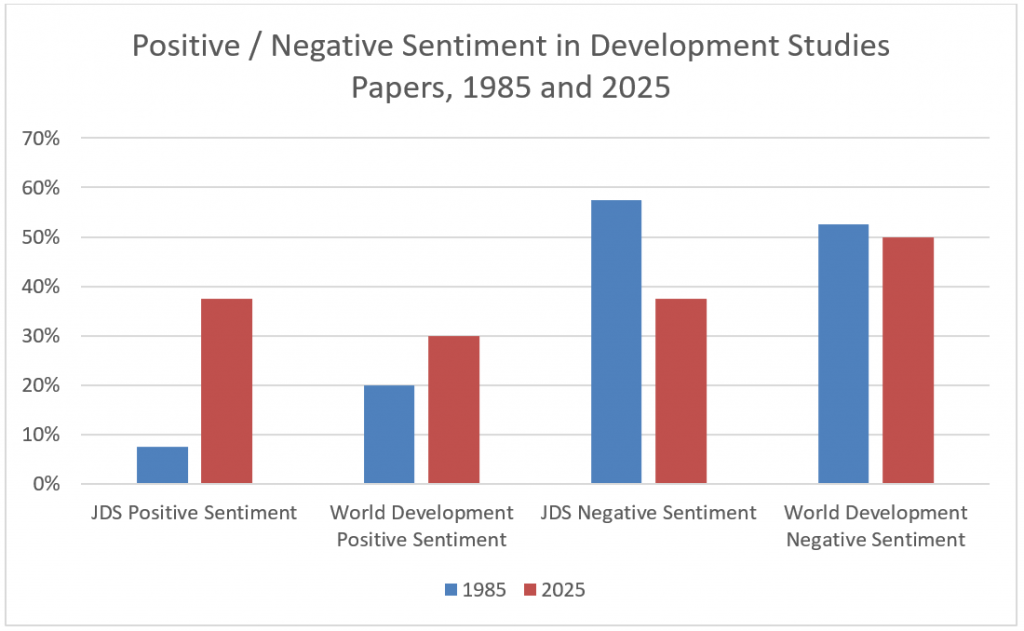

Of course, one thread of development studies has always engaged with this type of research and the idea can draw roots from the capability approach or the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach’s emphasis on the presence as much as absence of assets. There is also some evidence of a drift to the positive generally in development studies, though that likely depends very much on one’s starting point. Comparative sentiment analysis, below, of papers in two leading development studies journals, in 1985 and 2025, gives some evidence of this[1].

Reflecting on Positive Development Studies

Positive development studies would ask researchers to reflect on their own positionality and affect. How can our work not only critique the world, but contribute to its flourishing? What kinds of narratives do we amplify? What futures do we make thinkable?

Importantly, positive development studies would not ignore power. Rather, it reimagines agency, not just in terms of resistance, but in terms of construction. It shines light on changes already underway in social movements, mutual aid networks, food sovereignty initiatives, digital commons, and more. These are not perfect or free of contradiction but they are generative. They reveal that another development is not only possible, but already unfolding.

To embrace this orientation is not to abandon critique, but to expand the horizon of what counts as rigorous, relevant, and radical scholarship. It is to recognise that pointing out failure is not enough; we must also support imagination. After all, development is not only about transforming structures, but about cultivating the conditions in which people and ecosystems can thrive.

In this spirit, positive development studies invites us to be bridge-builders and story-weavers; to notice the green shoots of change, and to nourish them with care, insight, and solidarity.

[1] Based on analysis of 40 abstracts per year selected and starting backwards from the latest issue in each year (special issues/sections excluded; 1985 JDS sample stretched into 1984 to provide 40 abstracts). Sentiment analysis undertaken with Claude AI. Analysis with Copilot AI suggests a similar pattern but a much smaller shift. Much more rigorous analysis would be required to provide a definitive picture of trends including, as noted, the use of different starting dates for the baseline, and use of specialist sentiment analysis software.

Notes:

This article was first published on the ICTs for Development blog. A first draft of some sections of this text was generated via ChatGPT

This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Photo by Kyle Glenn on Unsplash

Please feel free to use this post under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Full information is available here.