Gabriele Restelli, PhD researcher, Global Development Institute

As Covid’s monopolizing power diminishes, immigration is ready to serve the purpose and fill the gap in headline news. Irregular migrants crossing the English Channel has gathered a lot of attention in recent weeks.

Immigration had been high on the European political agenda since 2014 and 2015, when Europe experienced record numbers of asylum seekers and migrants arriving in its territories, mostly via irregular routes. Nonetheless, the narrative of an “invasion” is rather misleading.

The “migration crisis”

In the year of the so-called “migration crisis”, 2015, record numbers of Syrians, Afghanis and Iraqis travelled to Greece and Italy. The total arrivals were slightly more than a million. While it does sound like a huge number, if all the EU countries had offered temporary protection to everyone proportionately to their own population, the whole “migration crisis” would have been solved with 1 migrant/refugee/put-your-label-here hosted every 50 thousand citizens. In other words, the whole Greater Manchester area would have contributed to solve the “migration crisis” by hosting just 50 persons. Five Zero.

The vast majority (78%) of the displaced population tends to find refuge within their own country (and are referred as Internally Displaced Persons, IDPs) or in neighbouring countries. Only a very small proportion of the overall displaced population (ca. 3%) travel to European shores.

Also, there is no evidence of dramatic changes in overall international migration trends. The total number of people living outside their country of birth (migrant stock) has remained relatively stable as a percentage of the world’s population since 1960, ranging from 3.1% to 3.3% in 2015. Only 0.75% of the world population emigrated in 2014 (migrant flow) just like in 1995.

No invasion nor migration crisis then. Rather a displacement crisis that has affected mostly non-European countries, whose resources were already strained. Turkey, Lebanon and Pakistan have been hosting by far the largest number (33% of the global caseload) of refugees.

The policy response

In response to the record arrivals in 2014 and 2015, significant funding has been mobilised by EU authorities and countries. Much of this funding has been explicitly deployed to deter refugees and migrants at Europe’s borders. Development aid packages for lower-income countries have been claimed as a tool to address the “root causes” of migration. One recent example is the $5 billion worth European Union Emergency Trust Fund for stability and addressing root causes of irregular migration and displaced persons in Africa (EUTF for Africa).

The use of development assistance to reduce migration is rooted in neoclassical theories of migration. In this view, people move from poorer to richer countries. If development programmes can redistribute wealth from North to South, they should lead to reduced migration by decreasing the economic gap between donors and recipients.

Is that an effective response?

Case Study: Central Mediterranean Route to Italy

In a recently published study, we attempt answering this question by focusing on Italy as a destination. Italy is one of three key entry points to Europe, via the Central Mediterranean Route. The study investigates whether that policy lever is effective, specifically: has development aid contributed to reducing irregular migration through Italy?

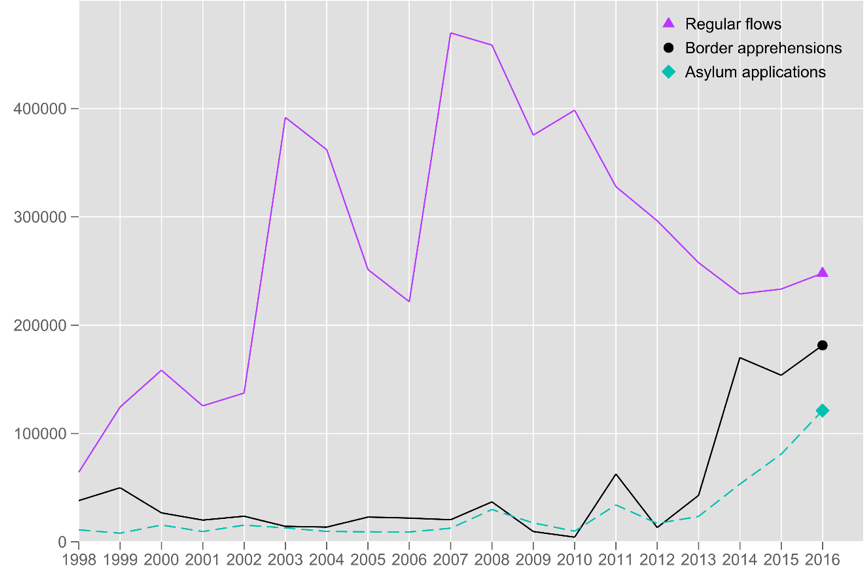

Until recently, authors have mainly measured migration flows through the number of visas and work/residence permits. But regular migrants are not the main target of European countries. Regular and irregular flows follow different trends and they involve countries of origin to very different extents. The study brings new evidence adopting two measures to directly test the effect of development aid on irregular flows. First, we use the number of illegal crossings detected along the Italian segment of Europe’s external border between 2009 and 2016. Second, we use the number of asylum applications lodged in Italy from 2003 to 2016.

Figure 2. Aggregate immigrant flows to Italy (1998 – 2016). Source: International Migration Database (OECD); ISMU and Frontex; UNHCR.

Key findings & Implications

Our main finding is that any effect of either bilateral or total aid on irregular migration is small, and tends to be statistically insignificant.

The most optimistic case we can make is that bilateral aid from Italy has a small deterring effect on the number of irregular migrants only from richer countries with per capita income of over 8,000 PPP$. To give a sense of the magnitude, taking the case of Iraq in 2016, this result implies a cost of around $1.8 million to deter a single border crossing.

When using the number of asylum applications, the most significant result is that the effect of bilateral aid from Italy is always positive and small. Increasing bilateral aid from Italy to a given country is associated with a small increase in the number of asylum seekers from that country.

Using the most common measures of regular migration, we find an estimated cost of deterring one migrant in the range of $4-$7 million. Other studies also reported negative significant results and stressed on the statistical significance to support the use of development assistance to reduce migration. However, the magnitude of these effects is very close to our estimates confirming high costs per deterred migrant.

Taken together the empirical evidence indicate that aid is not effective at deterring migration and it should be used for other purposes. There is no convincing evidence that development assistance reduced migration flows. In the best-case scenario, aid will have a very limited deterring impact on migration flows with high costs per deterred migrant.

To the contrary development assistance has been found to have positive impacts in other areas, such as healthcare and education. Spending should be concentrated where the added value is greatest. Allocating aid to respond to immigration concerns diverts resources from development objectives, while not being effective at delivering migrations control outcomes.

Further, migration is a complex process and there is no easy solution to its effective management. Efforts prioritizing mere deterrence have shown limited success. Based on available evidence, Official Development Assistance and development policy should not be advocated as easy fixes for such complex human phenomena. Policy efforts in the area of migration may be better placed at regulating movement in ways that maximize the gains for destination and origin countries as well as for the migrants themselves.

- The idea that aid and development slow migration is wrong – The Economist

- Read the Open Access article: Development Aid & International Migration to Italy: Does Aid Reduce Irregular Flows? Paul Clist and Gabriele Restelli

- Read the policy brief

Header image: Porta d’Europa, Lampedusa, Italy Door of Europe Source: Ron Dauphin on Unsplash

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.