Gindo Tampubolon, Senior Lecturer in Poverty, Global Development Institute

Maintaining health up to the centenary takes more than just genetic inheritance. Social determinants of health including wealth, income, education, social class and social networks throughout life combine to shape who survives and who thrives. In a recent chapter I wrote about a new set of findings that extends empirical evidence on the social determinants of health of people up to 100 years old (Tampubolon 2023).

First, it started very early in life. No survey has information from the stage ‘in the womb’ through childhood and adulthood to the stage in the tenth decade. But there are ongoing surveys which give information from the first to the tenth decades of life. Using these, I found the first decade, i.e., childhood matters, had several indicators which combined to have a lasting impact into old age. For example, whether there was sufficient physical facility (toilet, heating, overcrowding), whether there were books in the house, whether families had roots in place or had to move due to avoid debt obligations.

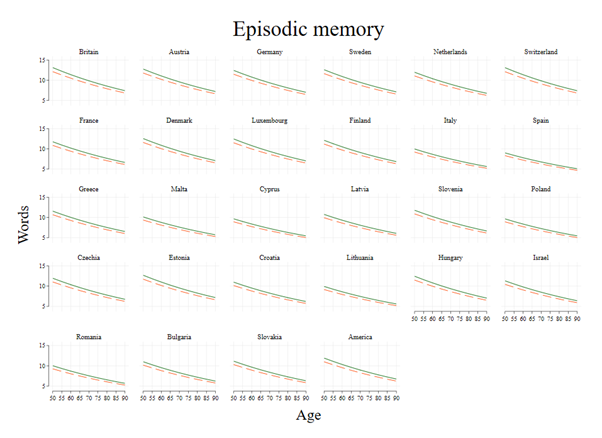

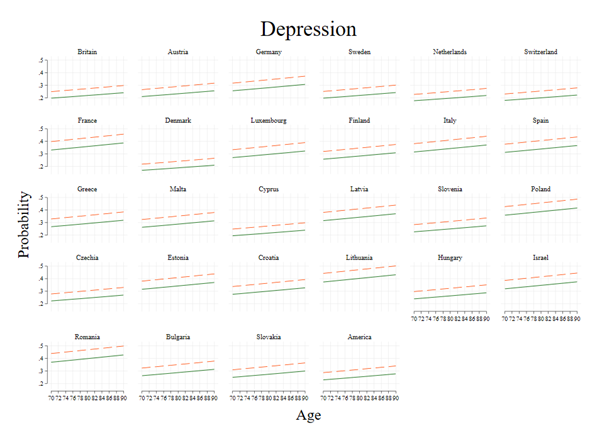

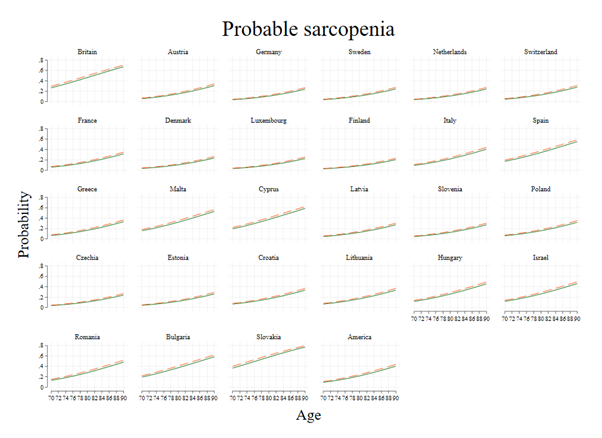

Second, it matters for the whole spectrum of health, be it physical, mental or cognitive. I investigated muscle function using dynamometer, which measures how strong your grip is; mental health using both American and European common mental disorder scales, and memory. Even after accounting for gender, age, race, wealth, education, social class, marital status and previous generation’s social class and health as a youth, the whole spectrum of health in old age is shaped by childhood poverty. I plot three short age range (70 to 90) for memory, depression and probable sarcopenia (muscle dysfunction).

Figure 1. Memory (number of words recalled) among the childhood poor (dash) and non-poor (solid) in older people aged 70 to 90 years in Britain, Europe and America.

Figure 2. Probabilities of depression among the childhood poor (dash) and non-poor (solid) in older people aged 70 to 90 years in Britain, Europe and America.

Figure 3. Probabilities of sarcopenia among the childhood poor (dash) and non-poor (solid) in older people aged 70 to 90 years in Britain, Europe and America.

Third, it matters less whether the health system is public, private or any mix. I investigated older people with use of the UK National Health Service as well as older people with use of largely private health providers in the US (or without one if they had no employment, hence no health insurance), taking in the older populations of 26 European countries with many combinations of health systems.

Fourth, it matters nationally – not only for city sample, or historic sample (or those experiencing certain eventful period such as famine). The US Health and Retirement Survey, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing and the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe are what I used – each is nationally representative and put together for this purpose for the first time. There are 28 countries and 78000 older people studied.

Last, childhood poverty matters for old age health because the poverty gets under the skin, into the epigenome. Using DNA methylation collected among older American participants in the sample I showed that the childhood poor underwent more adverse DNA methylation, making them age faster and succumb to dysfunction, disability and disease sooner. Childhood poverty associates with more adverse epigenetic changes throughout the life course; from childhood, youth, adulthood and old age. Childhood lasts a lifetime. And eliminating childhood poverty may prove to be a wise investment, even in countries which are already rich.

Top image: Photo by Johnny Cohen on Unsplash

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.