Dr Rory Horner and Prof Khalid Nadvi, Global Development Institute

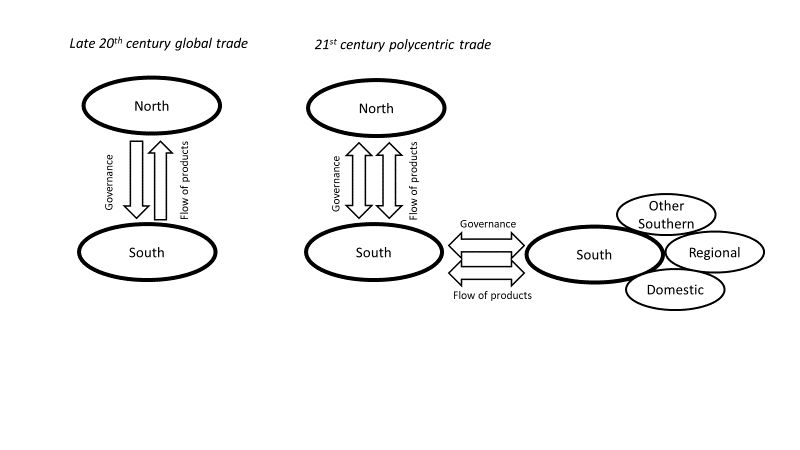

In a new, open access article published in Global Networks, we argue that Southern actors and Southern end markets have more prominent roles in global trade, requiring greater attention to the existence of multiple different value chains (VCs) serving different end markets – including domestic, regional and global. A growing portion of the global South’s trade is now beyond that of the global North, as a pattern of what we call “polycentric trade” has emerged.

Global value chains, and related global production networks, analysis has made valuable insights into the linkages that transform raw materials into final products and services, illustrating how value is created, and also differentially captured. A common, and arguably in our view a dominant, perspective amongst GVC and GPN scholars and policymakers has been an implicit focus on global trade involving North-South flows, stretching from initial stages of production in the global South to end markets in the global North. Indeed, many countries in the global South have been engaged in trade flows dominated by countries in the global North.

Now, however, whether it be the prominence of the global South in manufacturing exports, its growing share of consumption or the fact that the dominant trade direction is now South-South rather than South-North, considerable change is afoot. We draw on both “old” trade data (from Unctad) and new trade-in-value-added data (TIVA) to assess how the geographies of global trade are changing.

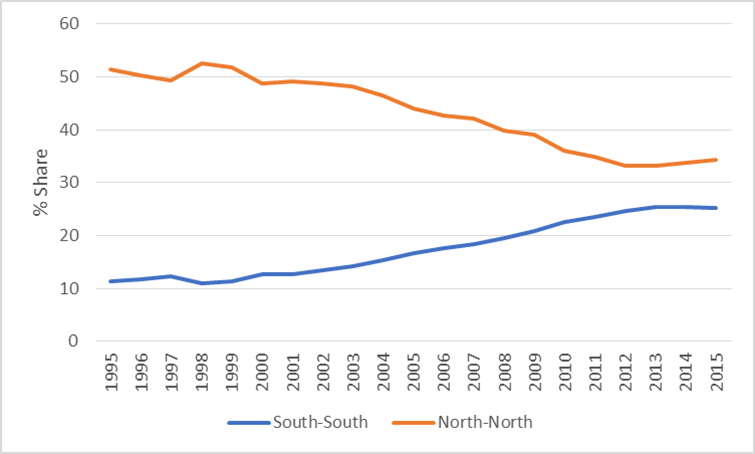

Trade amongst developing economies, known as South-South trade, has grown in relative importance as a share of world trade (see diagram below). It more than doubled from 11.4% in 1995 to 25.3% by 2015. Such South-South trade is dominated by intra-regional trade, especially within Asia. Yet, apart from a slight decline in intra-regional trade in the Americas, across all three major continents in the developing world, more exports are going to all other developing country regions and more imports are coming from such regions. Conversely, the European, North American and Japanese trade shares have fallen across all 3 major developing country blocks.

South-South and North-North shares of global trade, 1995-2015

Source: Authors’ analysis based on UNCTAD Handbook of Statistics 2016.

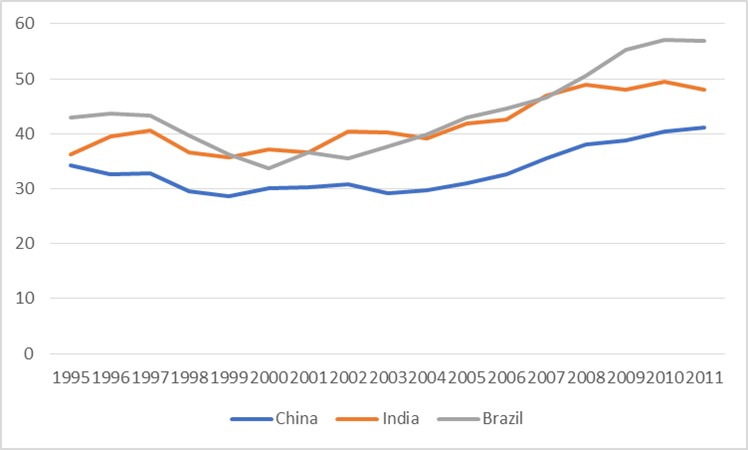

Developing economies are increasingly exporting to the large, developing economies, often termed the Rising Powers. Such growth is substantial, with developing economies share of the foreign value-added having increased from 38.9% to 52.5% between 1995 and 2011 in China; from 45.1% to 60.2% in India; and 31.8% to 47.2% in Brazil.

The case of Africa’s trade provides one especially illustrative example. 52.6% of the continent’s exports were to Europe in 1995, yet this share had declined to 37.3% by 2015. In contrast, the share of Africa’s trade with developing economies almost doubled in that period – from 25.6% in 1995 to 49.8% by 2015. The increase has been particularly driven by growing share of exports to China (from 1.2% to 10.6% over that time), but also intra-Africa exports (from 12.4% to 17.7%).

The value added generated in Rising Power economies which is exported also increasingly meets demand within other developing economies (see diagram below). For example, the share of China’s value-added in exports which goes to other developing economies has increased from 34.3% in 1995 to 41.2% by 2011. Similarly, for India, the share has increased from 36.1% to 48.1% and for Brazil from 42.9% to 57.0% over the same period.

China, India and Brazil – Share of value added in foreign final demand in developing countries

Source: Authors’ construction based on OECD TiVA database (December 2016 version).

Part of the expansion of South-South trade can be attributed to the expansion of GVCs, which have involved a growth of trade in primary commodities and of intermediate goods. For example, the high-profile case of the manufacture of Apple products involves considerable intermediates trade amongst developing economies within East Asia. Yet, significant amounts of final demand increasingly lie outside the developed economies. China substantially accentuates this trend, but even without China this shift is apparent.

Value chains are not always global. Under a pattern of more polycentric trade, firms in developing economies are participating in a variety of different value chains oriented towards different end markets. Producers in many industries, and increasingly policymakers, are placing particular emphasis on the (supra-national) regional and also domestic markets. For example, Kenyan farmers producing fresh fruit and vegetables are increasingly supplying regional value chains within East Africa as well as European supermarkets.

The upgrading strategies of farmers and firms in developing economies now involve negotiating the dynamics of multiple, overlapping VCs coordinated by different firms and oriented towards a variety of end markets. Rather than seeing the export market as composed of a single or even dominant GVC structure, producers increasingly weigh up a variety of different export market opportunities which may have different standards requirements and consumption preferences.

North-South vs. Polycentric trade

Having explored this new geography of trade, our analysis thus suggests that rather than emphasizing North-South oriented value chains/production networks, contemporary trade involves overlapping, multiple production networks oriented towards different end markets – domestic, regional and global – across both global North and South. “Value chains” and “production networks” do not necessarily automatically go together with “global”!

The article forms part of a special issue on the theme “Global production networks and new contours of development in the global South”, which collectively move beyond the South-North orientation of much value chains and production networks research. Look out for all the papers in Global Networks.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.