By Dr Eleni Sifaki, Research Associate, Global Development Institute

The geography of global development in the 21st century is shifting. Horner and Hulme call for a shift in academic development studies and development policy from ‘international development’ to ‘global development’ to address emerging global inequalities that transform dichotomies between developed and developing world.

Today the world is faced with global development challenges that transcend North/South divisions such as climate change and the refugee crisis. The 2015 SDGs reflect this change in understanding of development, as they are universal, applying to all countries irrespective of their development status.

In light of this shift in the geography and consequently the understanding of development, I have been working with David Hulme to examine the extent to which political parties in the UK have a) shifted from ‘international’ development to a recognition of ‘global’ development in response to economic, environmental and social challenges, and b) the extent of their commitment to global development.

What exactly ‘global development’ means is very much debated. Horner and Hulme contend that it involves a move away from strict focus on growth and countries following the development path of the North, to a focus on sustainability and social justice.

Drawing from this definition, we argue that recognition of global development involves a shift from focusing on ‘traditional’ development aid and free trade, to a more multi-dimensional understanding of development reflected in measures to address global inequalities and promote social justice. Commitment to global development is understood as the extent to which policy proposals are detailed and specific, with long-term horizons.

We’ve analysed the main political party manifestos for the 1997 and 2017 general elections and scored the development related content against a number of factors to produce an overall score (full methodology below).

Our preliminary findings overall indicate a visible shift in all parties from a recognition of ‘international’ development issues to a multi-dimensional and multi-directional understanding of ‘global’ development. There is clearly a greater focus on social justice and combatting global inequalities.

In 1997, the themes of ethical finance (including tax justice) and technology for development (such as R&D for health and climate change) were not addressed by any party. The themes of migration and global inequalities were partially addressed only by Labour and the Liberal Democrats. In 2017 these themes were addressed by the majority of parties, and in greater depth.

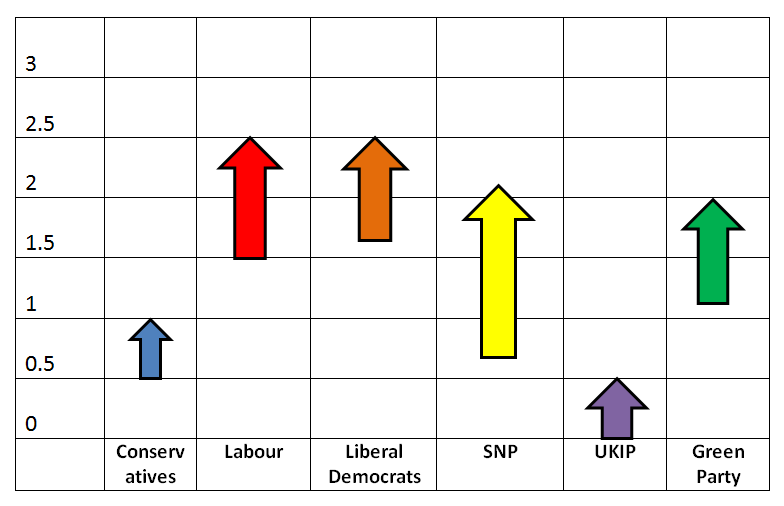

Contingent with this shift in understanding of development from ‘international’ to ‘global’ is the visible progress in commitment to global development. As Figure 1 below shows, all parties showed an increase in commitment in 2017. Labour, which was behind the Liberal Democrats in 1997, reached the same commitment levels with the Liberal Democrats in 2017. We attribute this to, among other factors, Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership and a shift of the party to the left. The biggest pace of increase in commitment is noted for the SNP which, following Brexit, engaged with wider issues for a long-term plan of Scotland’s place in the world.

Figure 1: Change in commitment to global development (mean commitment scores by party in 1997 & 2017)

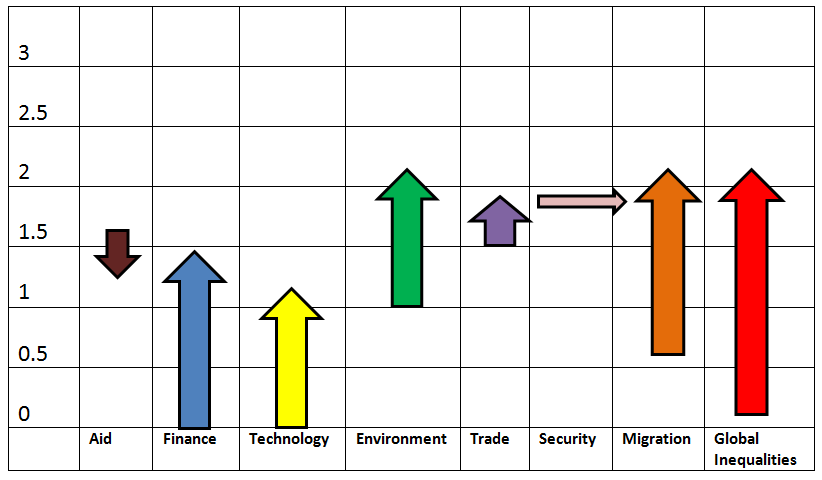

Figure 2 below shows the change in commitment for each global development theme across all parties. It shows that while there is a big increase in commitment scores for finance, global inequalities, migration, technology and the environment, there is a small increase in trade and security remained the same. This is consistent with a shift to a multi-dimensional understanding of development. However, there is a decrease in the score for aid. Although in 2017 all parties scored high in terms of aid quantity (all political parties except UKIP pledge to keep aid to 0.7% of gross national income and the Green Party pledges to increase it), they scored lower on ‘transparency’ and ‘maximising efficiency’ criteria of aid, leading to a lower overall score for aid in 2017. In particular, the Conservative party’s pledge to update the rules on how development assistance money should be spent, for whom and for what purpose raises concerns on whether funds will be directed to the most in need, and UKIP’s pledge to ‘close down DFID’ would have harmful consequences for aid.

Figure 2: Change in commitment per GD theme (mean commitment scores for 1997 & 2017)

We suspect that this visible shift towards both recognition of and commitment to global development is a consequence of three main processes. One is the gradual recognition by parties and voters of emerging global problems, such as climate change and the consequences of global inequality. The second set of processes relate to specific events such as the Syrian civil war and the ‘refugee crisis’ of 2015. The third set of processes derives from UK participation in UN agreements particularly the 2015 SDGs (which foster a global development approach in signatory countries), the Paris Climate Change Agreement of 2015 and the 2011 UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

In spite of the sustained attacks on aid and development from the right wing press over the last few years, and some party pledges to aid reform that are likely to have a negative impact on aid, there is a visible progress towards understanding development as ‘global development’ in UK party manifestos. However, we are sceptical as to whether for all thematic areas and across all parties this derives from pure ethical motives, or whether it arose from mutual interest and/or self-interest. As such, it remains to be seen whether this will be sustained, and what it will entail for the future of UK development policy.

Methodology

We investigated recognition and commitment based on 8 different global development (GD) areas. We used the Center for Global Development’s Commitment to Global Development Index (CDI) themes of aid, finance, technology, trade, environment, security and migration and added the theme of global inequalities, which includes access to health and education and gender inequalities. We evaluated recognition to global development based on the number of GD themes addressed by each political party in their manifesto. We evaluated commitment based on two of the characteristics of political commitment as outline by Brinkerkoff (2000): analytical rigour and continuity of effort. For each theme, we scored commitment of the political party from 0-3, with 0 for no commitment, 1 for low commitment, 2 for moderate commitment and 3 for high commitment. We then came up with a mean score of commitment to GD for each political party for each year. To explore commitment by GD theme, we calculated the mean score per theme by all parties for 1997 and 2017.