Armando Barrientos, Professor of Poverty and Social Justice, Global Development Institute

The aim of this blog post is to throw light on Universal Basic Income (UBI) as a social policy. In current policy debates UBI proposals have a number of objectives: to address inequality, to provide a basic income flow, to address the labour market effects of automation, etc. I have chosen to focus on the role of UBI in the context of poverty reduction.

When assessing social policy, at least three types of evaluation are relevant. First, does the policy proposal fit with the ethical values of particular societies? By ethical values I describe deeper shared norms on the parameters of economic and social cooperation. Second, is the policy proposal likely to generate the outcomes that are expected? All policies are assessed on the basis of their effectiveness. Third, is the proposed policy likely to command political support? This is crucial to ensure the sustainability and legitimacy of the policy. This post sketches a brief assessment of ethical fit, effectiveness, and political support of UBI proposals as an instrument of poverty reduction.

I once had a chance at a Seminar to ask Philippe van Parijs a leading supporter of UBI the following: what is the question to which the answer is UBI? I asked the question because of the very wide range of social problems UBI proposals are supposed to ‘solve’. UBI proposals are the ‘snake oil’ of social policy. His response was illuminating, the UBI is an answer to the question: what institutions are required in a just society.

UBI proposals have a close fit with egalitarian ethics. But there are many forms of egalitarianism around and we need to be more precise. ‘Instrumental’ egalitarians favour equality because of their effects on, say, democracy or growth or welfare. They see equality as a means to achieve other ends. For the most part, debates on inequality in international development draw from this approach. An issue with the instrumental approach is that if it could be shown that these objectives could be achieved in its absence, equality would loose its force.

‘Intrinsic’ egalitarians, on the other hand, see equality as an end it itself. They argue that societies ensuring equality among their members have a greater ethical value. This approach is very attractive, but could be too demanding. ‘Intrinsic’ egalitarians ought to favour equalising down to the level of the worse off.

Poverty reduction finds stronger foundations on ‘priority’, the view that benefits to disadvantaged groups in society haver higher ethical value. Prioritarians avoid the levelling down objection to ‘intrinsic’ egalitarianism. Strictly, priority is broader in scope than poverty, or at least broader than the poverty views dominating international development debates. There is no reason why priority should stop at the poverty line.

The main point is that while UBI has a close fit with egalitarian perspectives, ‘instrumental’ or ‘intrinsic’, poverty reduction has a closer fit with prioritarian views. There are important differences in the ethics of UBI and the ethics of poverty reduction policies. UBI supporters find the absence of selection hugely attractive, whereas proritarians find this intensely problematic.

The hard question to answer is whether low- and middle-income countries’ polities are ‘egalitarians’ or ‘prioritarian’, but we’ll come back to this question below.

I now would like to address the issue of effectiveness. Are UBI proposals likely to address poverty? UBI proponents give an affirmative answer to this question. Setting the UBI level in a particular country at or above the poverty line would effectively do away with poverty. However, this is not straightforward, at least for the following three issues.

First, a comprehensive UBI reaching all residents with a transfer at least equal to the domestic poverty line could eliminate consumption deficits among those in poverty. However this is perhaps too restrictive a view of poverty. We commonly measure poverty as deficits in income or consumption, but the underlying causes of these deficits are to do with productive capacity. Households are in poverty because the resources at their disposal are insufficient to generate a basic level of income or consumption. Poverty profiles invariably find a correlation between poverty and low levels of education and health, limited access to credit or land. To the extent that poverty is rooted in insufficient productive capacity, consumption subsidies are a necessary but not sufficient condition to poverty eradication. Redistributing productive capacity, not just consumption, is essential to eradicate poverty. UBI proposals fall short in this respect. For more on this point and in the context of European welfare states see “Commodification and Decommodification: A Developmental Critique.”

Second, a well-designed and well-implemented UBI could reduce consumption poverty and inequality when supported by progressive tax systems. In this context a UBI would redistribute from the better off to the worse off. But in fact low- and middle-income countries lack progressive tax systems. Studies on tax-transfer systems in Latin America from the Commitment to Equity initiative, for example, conclude that these are largely neutral in their effects on redistribution. In some countries, Brazil for example, taxes and transfers actually increase poverty. There is no guarantee that, in the context of neutral or regressive tax and transfer systems, a UBI would reduce poverty and inequality.

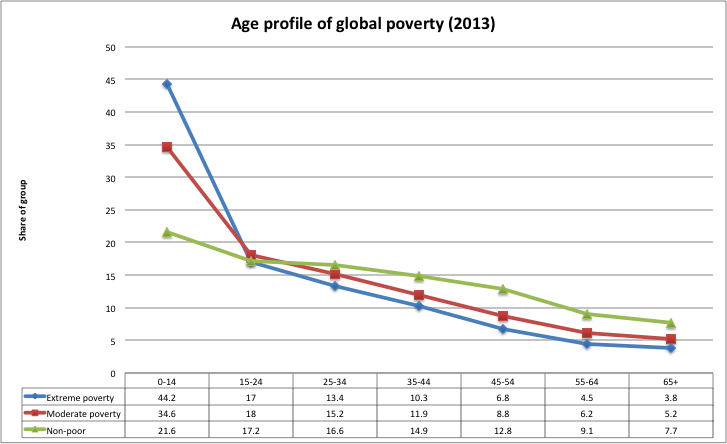

Third, current UBI proposals focus on transfers to adults only, but the majority of people in extreme poverty in the world are children. See the Figure below for an age profile of global poverty. Excluding children significantly reduces the potential poverty reduction effectiveness of a UBI.

Data Source: Castañeda, Andrés, Dung Doan, David Newhouse, Minh Cong Nguyen, Hiroki Uematsu, and Joao Pedro Azevedo. 2018. “A New Profile of the Global Poor.” World Development 101: 250–67.

The fact that UBI proposals are focused on the redistribution of consumption and on adults together with the absence of progressive tax systems in low- and middle-income indicates their potential poverty reduction effectiveness is limited.

Is there political support for UBI? This is a hard question to answer with available evidence.

There is firm evidence of political support for policies to address poverty. Most low- and middle-income countries have anti-poverty strategies and policies. Through the Millennium Development Goals and the Sustainable Development Goals, the international community has committed itself to the eradication of extreme poverty. The expansion of social assistance in low- and middle-income countries provides a very practical confirmation of political support for poverty eradication.

By contrast, few examples of large-scale and comprehensive UBI or UBI-like initiatives come to mind. Iran’s 2009 Subsidy Reform Plan was developed to address mounting costs of energy and food subsidies. The Plan intended to establish a transfer to compensate the poorer half of the population. But data constraints eventually led to a UBI-like transfer in 2010 reaching just over 90% of the population. Subsequent legislation was approved in 2013 aimed at excluding the richest top third of the population, gradually restricting the transfer to lower income groups.

Mongolia’s attempt to redistribute natural resource revenues led to the introduction in 2005 of a targeted child benefit. It became a categorical child transfer in 2006. In 2010 the transfer was extended to all citizens. This proved unsustainable and reverted to a categorical child transfers in 2012. Reporting on an attitudinal survey taken at regular intervals during this period which asked respondents for their views on how natural resource revenues should be used, Yeung and Howes point out that the share of respondents supporting direct redistribution fell from 17% before the universal transfer was introduced to 8% after it was discontinued. By contrast, the share of the respondents supporting the use of the revenues for long-term social development doubled from 19% to 40% in the same period.

More research is needed to gauge the level of political support for UBI proposals in low- and middle-income countries. Mongolia and Iran might not be representative of trends elsewhere. Political support for poverty reduction policies is strong and widespread in low- and middle-income countries. However, as was noted above, tax and transfer systems in these countries fail to carry this commitment through fiscal policy. While the jury is out on this issue, my sense is that our societies are ‘prioritarian’.

For the last two years Armando Barrientos has been assembling a new database of social assistance indicators for developing countries for the period 2000-2015. The beta version of the database is online now with the with data for Latin America. The final version of the website will be live in early September.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole