By Daniele Malerba

Inequality is a topic of major interest nowadays, with recent reports showing that the richest 62 individuals possess more wealth than the bottom half of the global population. But this attention has not always been there.

One the main drivers of this new “inequality movement” has been the recent recession, coupled with the stagnant incomes of the middle classes. But Branko Milanovic, one of the pioneers of this movement, discussed also the importance of data improvements in the recent trend of inequality analysis.

During a masterclass with PhD students at the Global Development Institute, he argued that the increased availability of household level data has been impressive. This is especially true for Africa where the coverage rate increased by more than 20% in the last 20 years. Current advancements in the availability of data also includes: fiscal information to complement household surveys, the use of top incomes in inequality estimates (as they are not represented in common household surveys) and information on inequality of wealth. Improvements in the amount of information available is also helping to develop new fields of inquiry, such as the concept of inequality of opportunities as opposed to inequality of outcomes, the decomposition of inequality and growth, and historical inequalities.

Moreover, the increased coverage of data and the effects of globalisation, has enabled the study of global inequality, the inequality between all individuals in the world, regardless of country. In his public lecture, Milanovic, who has been assembling data from different countries in order to build a global income distribution, explained his findings and the policy implication for some of today’s main issues, such as migration and the future of the middle class.

Inequality between and within countries

To better understand global inequality, it is important to separate it conceptually it into inequality within nations and inequality between nations.

Inequality within countries, measured by the national Gini coefficients, increased in most nations between 1988 and 2008. The increase was mainly driven by market inequality (wages and returns from financial assets), which was cushioned by the use of redistributive capacity to make final disposable income less unequal.

More interestingly Milanovic pointed out that the majority of countries experiencing increasing inequality, such as the US, might be on a second Kuznets curve. On the other hand countries like Brazil (and many other LACs) and China are still moving along the first Kuznets curve. Their experience of decreasing inequality is the result of increased spending on social transfers, reduction of the education premium and minimum wages.

Inequalities between nations, which is usually conceptualized as looking at differences between country’s mean incomes, has decreased in the past 20 yearsmainly due to growth in Asian countries. Despite this, some facts remain striking. The figure below shows, for example, that not only is the mean income in Denmark’s remarkably higher when compared to a group of African countries; but there is also no overlap between the income distributions. This means that the poorest group in Denmark is richer than the richest group in Uganda (excluding billionaires which are not represented in household surveys). Similar patterns can be found comparing many rich and poor countries.

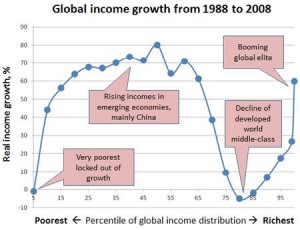

Finally, what if we look then at global inequality as a whole? First of all 1988-2008 was the biggest reshuffling on incomes since the industrial revolution. Decline in global inequality was accompanied by four main features: the large gains captured by the top 1% of the global distribution, the growth of the Asian middle-class, the “zero-growth” of the middle class of many western states such as the US, and the stagnant incomes of the bottom of the global distributions. The second and third points brought the emergence of what Milanovic calls the “global middle class” who earn between $10 and $100 US dollars a day. The size of the rising Asian middle class also meant that the global median income has been rising at a faster rate than the global mean income.

Secondly, the major driver of inequality is still location (between countries), meaning the country where you are born largely determines your income. As shown previously using the example of Denmark and African countries, the poorest group in one country might be richer than the richest group in another country. This is a change from 1850, when inequality was more prevalent between class (within country inequality) and location, representing Marx’s “world of classes”. The projections for the future, with the rise of Asia suggest the continuation of the current trend of diminishing importance of the location component, which might translate into further reduced global inequality (as well as structural change of the inequality decomposition).

The implications for migration

Milanovic outlined a number of policy implications that could reduce global inequality. The first possible solution is to increase growth in poor countries (and their mean incomes). The second tool is migration.

When people migrate from poor to rich countries their income increases. Given the importance of the location as a determinant of inequality, the gains are potentially large. In addition to this, the costs associated with travelling are reducing, meaning that labour supply is increasingly being globalized – in a way that hasn’t happened previously.

Does this mean advocating for growth in the rate of migration from poor to rich countries? Milanovic proposes trade-offs between migration and citizenship rights; this means allowing intermediate cases of partial citizenship, in order to mitigate migration flows. Regardless of the specifics, his proposals suggest one important thing: we need to get serious about global inequality and its consequences.

You can listen to Branko Milanovic’s lecture ‘Globalization, migration and the future of the middle classes‘ in full here: