Dr Nicola Banks , Lecturer, International Development: Urban Development and Global Urbanism

Christmas is a time for giving, when people think about how to extend their generosity to those in greater need. We put additional items in our trolley to donate for food banks, have a clear out of blankets, warm clothes or toys for local charities, or search for unique charity gifts that help disadvantaged people overseas.

Since the financial crisis, international aid and development spending has been in the firing line. The British government’s pledge to spend 0.7% of gross national income on aid has acted as a lightning rod for criticism from the right-wing media, who claim the money is mispent and that it should be spent in the UK.

My colleagues and I were interested in exploring the effects of austerity and the continuing narrative of aid scepticism on the development sector. So we embarked on a quest to map the UK’s development NGOs, including charities who help in emergency situations as well as those funding longer-term development projects.

We’ve now produced a database of over 900 development NGOs that spend over £10,000 a year, tracking their incomes and expenditures from 2009 to 2015 (the last year of publicly available data). In 2015 alone, we found that the British public contributed 40% of the sector’s overall income of nearly £7 billion – equivalent to around half of aid spending of £12.2 billion by the government in that year.

Public keep on giving

The public is by far the major donor to British NGOs working in international development, contributing more to the sector than government grants, other charities and business combined.

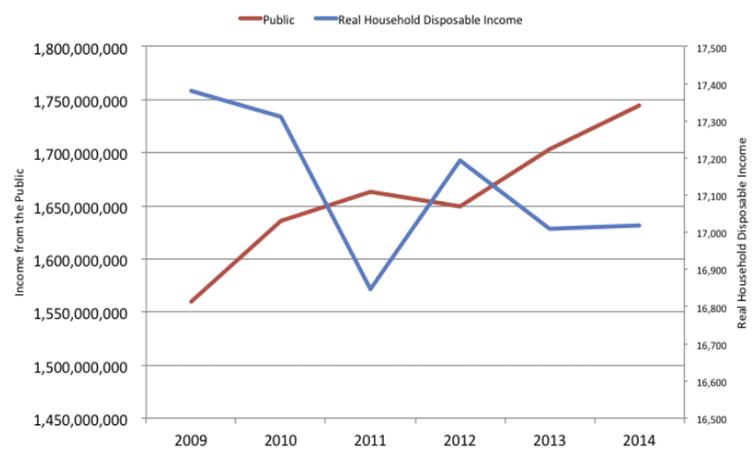

Donors have remained committed to this generosity, even as incomes have been squeezed. Public giving did not followed downward trends in real household income – their peaks and troughs have been diametrically opposed across the period we looked at. At first we thought these sustained and increasing contributions were largely driven by rich philanthropists whose incomes may have been largely protected since the financial crisis. But at a recent event we held on public attitudes to international development we were challenged on this.

Fundraisers told us they were not surprised that donations have increased even as incomes have been squeezed, highlighting ancedotally that regular members of the public, rather than major donors, have always – and remain — their biggest funder.

Changes in giving from the public to development NGOs and real household disposable income available in the UK.

International development is just a drop in the ocean when it comes to the UK’s overall charitable funding. An analysis of Charities Commission data highlights that most charitable expenditure – £53 billion out of £68 billion in 2015 – is spent by charities that operate only in the UK. Charitable expenditure on international development is less than 10% of the total of what charities spend.

The British public has provided the backbone to a sector that has shown sustained growth since the early 2000s – in both the number of organisations and in total funding. Up until 2015, the last year of data available for our analysis, there was no sign of a decrease in the number of organisations or overseas expenditure. Income across the sector is distributed highly unevenly, with the 77 largest organisations (8% of the 900 NGOs in our database) accounting for over 90% of the sector’s expenditure. Our data shows government funding going almost exclusively to NGOs with incomes over £1m and a large increase in government funding to NGOs spending more than £100m since 2010. This makes income from the public particularly important for small to medium-sized development NGOs earning less than that.

Concerns for the future

Our research may show a largely positive situation for the UK’s development NGOs, but the picture is not universally rosy. These findings are at odds with growing concerns within the sector, include unease around a funding environment that is getting harder and harder, with growing competition and a public that are getting less receptive or more hostile to international development causes.

The data is not yet available to look at how funding trends continued across the sector in 2015 and 2016, but the people in NGOs we’ve spoken to feared that the sustained commitment they had seen until recently was no longer looking as robust, and that new data protection changes could hinder their fundraising and campaigning activities.

Our findings only track trends until 2015, the latest year when income data is universally and publicly available. There have seen many changes since, including a Brexit vote that deepened the “charity begins at home” narrative. Both academic colleagues and those working in NGOs fear this will weaken the British public’s engagement with the overseas charitable sector.

The Gates Aid Attitude Tracker project has been tracking changes in attitudes to aid across the UK, revisiting the same households every six months since 2013. Their findings suggest that the number of people in its sample donating money to international development causes dropped in the second half of 2015 and has remained lower ever since. Economic issues and attitudes to immigration were found to negatively influence public engagement in the sector.

Changes at home will be exacerbated by UK-based NGOs potential losses from EU development funding, for which they may no longer be eligible after Brexit. A post-Brexit weakened exchange rate has also increased the costs of funding projects and infrastructure overseas: a double-whammy. Now is the time to reaffirm our commitments internationally as well as at home.