By Armando Barrientos, Professor Emeritus of Poverty and Social Justice at the Global Development Institute

Discussions surrounding how Latin American states can support less advantaged citizens have often looked to European ‘welfare states’ as exemplary models for reducing inequality and tackling poverty. Chile’s young President Gabriel Boric, for example, ran an election campaign built on promises to dismantle neoliberalism through increased public spending and ‘welfare state’ provisions, among other things.

In some ways, it’s easy to see why the ‘welfare state’ model is appealing. Nordic countries, for example, are often praised for their universalist approach, providing a strong financial safety net for citizens, as well as promoting equal opportunities through well-funded public services.

But what if ‘welfare states’ represent the exception to the rule when it comes to supporting less advantaged people throughout the world? What if the uneven nature of capitalist development means Latin American states cannot usefully implement some of Europe’s tried-and-tested welfare mechanisms? This article explores how theorists of social protection can better understand and address such a problem.

What is social protection and the ‘welfare state’?

Taxation socialises private income which governments invest in services and income transfers. Services like education and health are transfers in kind, while income transfers to support families and the elderly are transfers in cash. Social protection encompasses income transfers.

‘Good’ governments are meant to tax the better off and assign these resources to fund services which maximise opportunity, while using income transfers to support workers and families especially from less advantaged groups.

Under capitalism this is an uphill task, as the workings of the economic system generate poverty, vulnerability, and inequality as a matter of course. Social protection plays an important part in mitigating these outcomes, although it often works imperfectly. We need a theory of social protection to understand its effects.

European countries recovering from World War Two constructed ‘welfare states’, literally states committed to ensure adequate levels of welfare in the population. High levels of taxation funded universal services reaching all and income transfers supporting workers and families through employment and life course events. In theory, welfare states would mitigate the worst consequences of capitalism, while ensuring rising productivity and democracy. (Spoiler: This is a very rosy picture. The reality is far more challenging, but here I am focusing on the ideal.)

Comparing Europe to the rest of the world

What about the rest of the world? It is not surprising that researchers and policy makers elsewhere embraced ‘welfare states’ as the ‘end of history’. Theories of social protection appeared redundant, replaced with comparative measures of advancement towards a ‘welfare state’ (see relevant millennium development goals [MDGs] and sustainable development goals [SDGs]).

There appears to be some global convergence in services – education in particular – but there is little global convergence in social protection.

Towards a general theory of social protection

What if ‘welfare states’ are a special case in the global evolution of social protection? Then we need a ‘general’ theory of social protection. We need to start with an understanding of the kind of institutions in place in different parts of the world and study their effects. Research can be guided by the proposition that social protection institutions stratify wage earners in terms of employment, protection, and incorporation.

Social Protection in Latin America: Causality, Stratification, and Outcomes implements this approach for the region. Social protection institutions support specific groups of workers and their families. Occupational insurance funds support workers in large firms. Historically, they emerged with state-led development policies and as part of elite efforts to co-opt labour organisations. Individual retirement savings plans severed the link between social protection and occupational groups. Social assistance decouples protection from employment and facilitates the incorporation of low wage informal groups.

Social protection in Latin America is fragmented and unequal. This is not accidental, a blip in the march towards a ‘welfare state’, but the consequence of existing institutional structures.

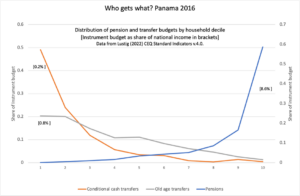

The figure shows social assistance budgets benefiting mostly low-income households while pension budgets benefit mostly high-income households. The pension budget is over eight times (at 8.6% of national income) larger than the social assistance budget (0.2%+0.8%=1% of national income). The Pensions budget does not include workers’ contributions, the Pensions budget net of contributions is 4.1% of national income.

Photo by Leon Overweel on Unsplash

This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Please feel free to use this post under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Full information is available here.