Chris Jordan, Communications and Impact Manager, Global Development Institute

For most development-focused academics, the main reason they join the profession is to contribute towards positive social change. Contrary to the increasingly outdated image of out of touch academics, IDS’s James Georgalakis recently observed, “hard as I look, I can’t see any ivory towers – only scientists desperately worried about fake news, academic freedoms and results-based research agendas.”

Traditionally, many joined Development Studies departments following years of practice in NGOs and international organisations, seeking the space to inform or challenge the broader intellectual frameworks that guide development, rather than working on individual projects. The academics I work with at the Global Development Institute are incredibly well networked, attuned to the big issues on the horizon and motivated to do something about them.

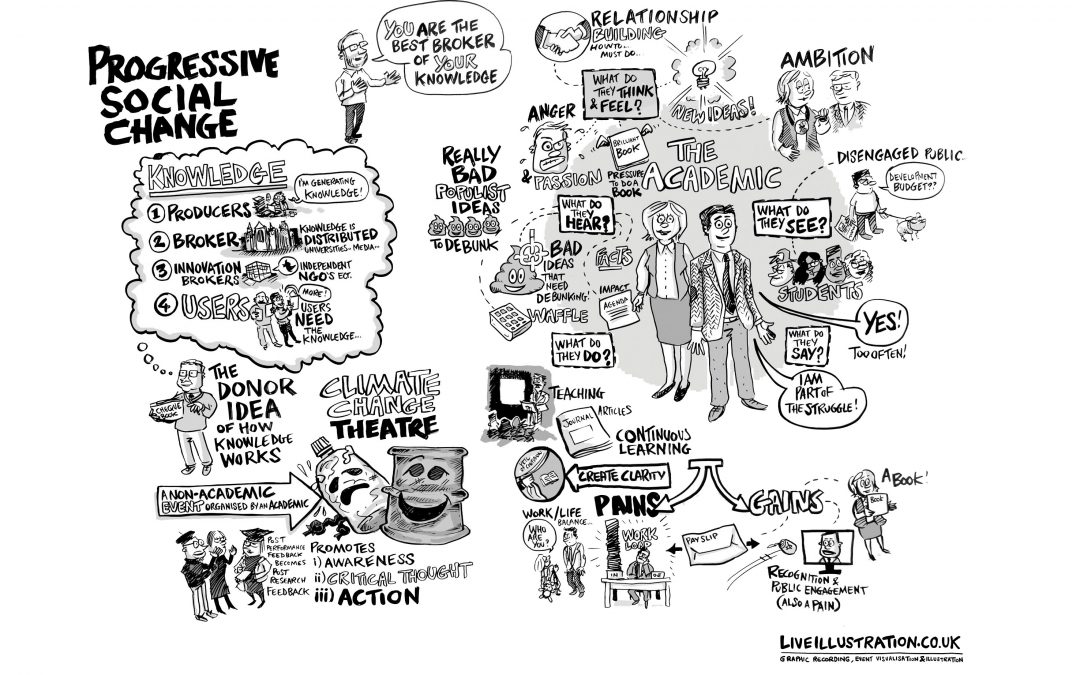

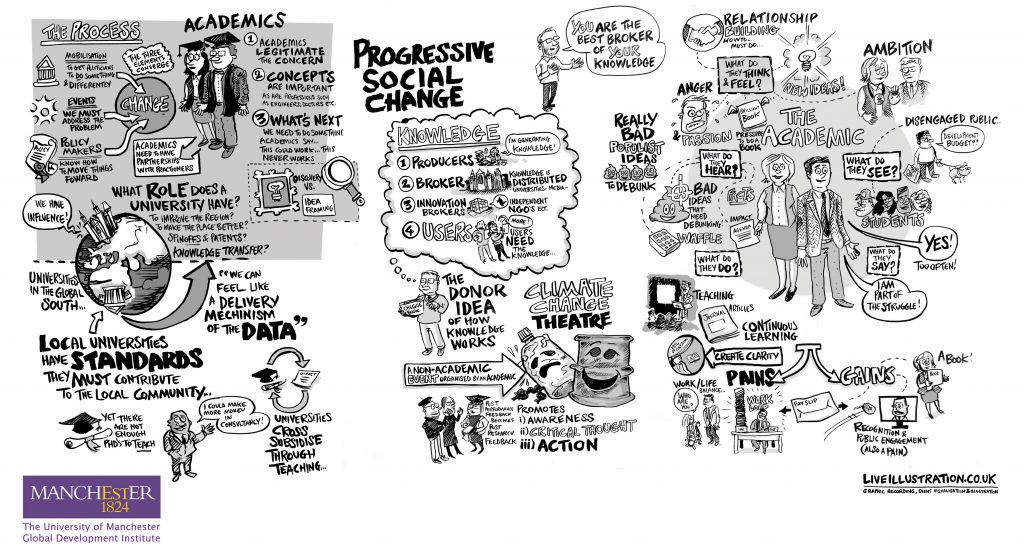

But despite the practical orientation of development studies and the intrinsic drive of most academics working within the discipline, it’s not always clear exactly how academics with particular specialisms, at different stages of their career, can most effectively contribute to changing the world for the better.

Academics in the UK are now working in a context in which ‘Impact’ is demanded more and more by donors and assessment agencies. There are clear benefits to this agenda, which helps to raise the status of engaged, problem-solving research and can provide the resources researchers need to ensure their ideas gain traction beyond academia. But there’s also a risk that the impact agenda ends up instrumentalising research, possibly squeezing out the potential for more conceptual and theoretical work.

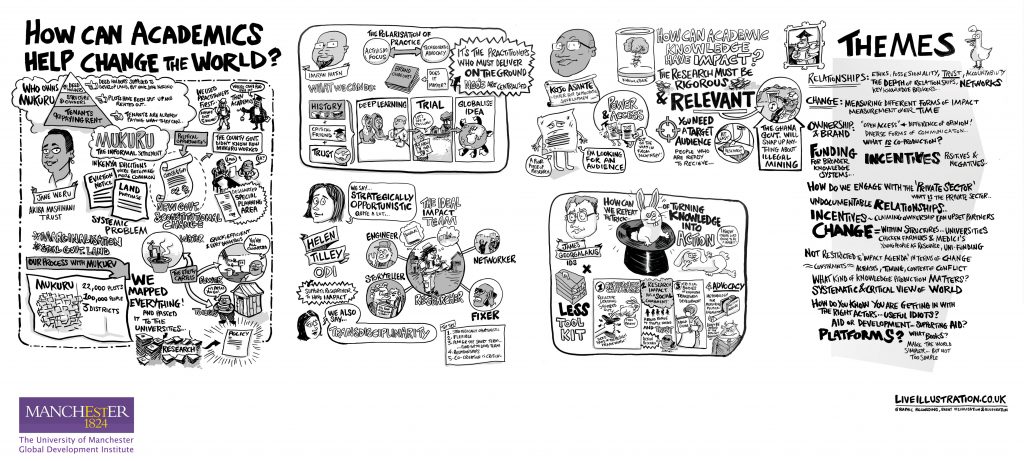

As the effectiveness of the development industry as a whole comes under increasing scrutiny, the Global Development Institute recently brought together a range of academics, think-tankers and practitioners to grapple with the issues. The discussions were broad ranging, but for me some of the key challenges and potential solutions were:

-

Does a narrow focus on the ‘impact’ on individual research projects diminish the potential for more transformative change?

Funders of development research (particularly DFID) increasingly want to see (and are willing to fund) ‘uptake’ activities to maximise the chances of projects achieving impact. Indeed, I owe my first job at the Global Development Institute to DFID pushing for a communications and uptake role after awarding a research grant and I’m in no doubt about the benefits of providing decent communications and uptake support to engaged, but over-stretched researchers. However this does tend to incentivise that project focused impact, which may undermine the prospects for broader, transformative change in the longer term.

Would Marx, Sen or more recently Ha-Joon Chang and Dani Rodrik have changed development paradigms if all their energies had been focused on chasing the next research grant and then proving the results were ‘value for money’? Most universities are woefully under resourced to identify and support the longer term research agendas that have the most transformative potential – and yet this is their comparative advantage over think tanks or consultants. By overly projectising research and the short term impacts they produce, are we in danger of undermining the intellectual space and creativity that universities are based on?

So how can we guard against the instrumentalisation of research? Challenging research funders to invest more in longer term agendas rather than short term, policy oriented projects (which often see their windows of opportunity close before firm conclusions are reached in any case) is an obvious place to start.

Individual academics have a role too. Rather than simply churning out ‘pathways to impact’ statements to support grant applications, they should spend more time strategically thinking about their own longer term trajectory towards achieving change. Just as an NGO change campaign has a broad 5-10 year vision of what it’s aiming to achieve sitting alongside a one year strategy and plan, academics should try to identify their long term theory of change and how they plan to pursue it. Doing so would also help academics to more strategically manage the many competing demands on their time, while being savvier about which shorter term impact opportunities they pursue and how they can best contribute to more transformative change over their careers.

-

Academics should think more about their role in movements or epistemic communities, which are better able to shift norms over time.

There’s a danger that putting more emphasis on achieving transformative change reinforces the idea of the ‘superstar academic’, whose individual brilliance sweeps all before, while everyone else ambles along in their wake. However, almost all significant change comes about as the result of a much broader set of networked actors working to a common end (even when a particular individual takes the credit).

As such, academics should pay close attention to the existing collection of other researchers, NGOs, community organisations, businesses, political parties, government officials and media advocates clustered around issues they care about. If these clusters are weak, looking how they could be strengthened might be an appropriate tactic. Likewise, in more established movements, being clear on what an academic can bring to the party will help to maximise the effectiveness of that individual within the broader process of change.

-

Is the research impact agenda undermining the longer term impact universities produce via teaching?

In the US, all successful universities are quite clear that the positive impact they have on society is primarily through the teaching and guidance of students, many of whom eventually assume influential positions beyond academia. In spite of the ‘research led teaching’ positioning of Russell Group universities in the UK, it seems that we don’t have a clear sense of how to value the impact of alumni. While most universities have invested in building up their alumni relations teams over the last few years, perhaps there has been too much focus on cultivating alumni as a source of additional funding and not enough on maintaining a mutually beneficial relationship with graduates. Not only does this have the potential to open doors for the current notion of research impact, it provides a way to celebrate the positive change alumni are creating and better identify where their experience at university played a role.

-

Do we need to think more about when change goes wrong?

Almost all processes of change involve winners and losers. In the complex environments development researchers operate in, it’s not always clear precisely how we have influenced change and the role of unintended consequences in the longer term. Determining, let alone policing, the ethical implications of research and impact in the real word is difficult and contentious – but that doesn’t mean we should ignore it.

One practical step would be to create regular impact forums within universities, possibly involving academics from a range of relevant disciplines. As well as sharing experiences and identifying what works (or doesn’t) in particular situations, impact forums could act as a form of ethical peer review, challenging academics to sharpen their practice in the short term, while providing an institutional space to support researchers achieve more transformative change in the longer term.

Love what you say about the focus on ‘impact’ potentially diminishing transformative change. It’s completely true!