By Dr Robbie Watt, who gained his PhD from the Global Development Institute and is now a Lecturer in International Politics at The University of Manchester.

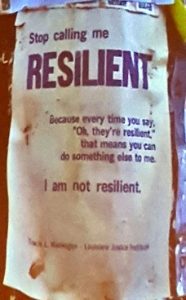

Image: Because every time you say, “Oh, they’re resilient,” that means you can do something else to me. . Image source: https://twitter.com/JulReid/status/405024781772148736

‘Ohh, resilience.’

When I mentioned resilience, the topic of that evening’s GDI lecture to social worker friends in a Manchester pub, their reaction was cynical. ‘We hear about resilience all the time,’ they said disdainfully. Manchester social work, facing austerity and cuts, deploys resilience terminology to justify withdrawal from tragic situations. Don’t worry, they are resilient.

Professor Katrina Brown, Chair in Social Science at the University of Exeter, is by no means ivory tower bound nor isolated from stories such as these. In New Orleans, post-Hurricane Katrina, people objected to being labelled resilient, and Professor Brown was there to notice.

The language of resistance and political struggle can be avowedly anti-resilience. Yet Professor Brown sees resistance as (just?) one part of resilience. Naming grassroots resistance and struggle as (mere?) aspects of resilience invites controversy because resilience has been criticised as a neoliberal and depoliticising concept that speaks to ideas of self-reliance and technocratic governance. Hence there is a tension involved in calling resistance efforts, which often challenge neoliberal policies, as intertwined with resilience.

Nevertheless, resilience is a sufficiently broad concept that Prof Katrina Brown can escape definitions that conform to neoliberal ideas. Indeed Prof Brown’s work, including her recently published monologue Resilience, Development and Global Change, is critical of business-as-usual policy discourses on resilience. Her aim is rather to reclaim resilience as a rich analytical concept that can help us to understand processes of change in dynamic socio-ecological systems, where people and landscapes interact with power and agency.

In her excellent lecture, Prof Brown identified three components of resilience – resistance, rootedness, and resourcefulness – giving colourful examples of each. She then showed us how resilience can be articulated in an empowering fashion through participatory theatre. I turn to each below.

Resistance – the heart of resilience

In resistance, Prof Brown described examples of people defying social structures and building new ones, at the same time as they recognise the complex interactions between politics, practices and changing ecological situations. In remote Orkney, Orcadians resist central government and express desire for self-determination, articulating a politics responsive to local conditions. In East Africa, people struggle over fishing resources and water access. In coastal England, homeowners contest the violent policies of ‘managed retreat’, whereby houses may be lost to the sea. If resistance is intertwined with resilience, then for me, it is the heart of it. Resistance drives the beating pulse of a sensation that you are standing up for something important.

Rootedness – the soul of resilience

Rootedness – the soul of resilience

Whereas resistance considers power, rootedness is about place. We, as people, are attached to the local environments in which we live, work and play. Places carry histories and meanings that evoke emotions and inspire identities. This rootedness, Prof Brown argues, is what grounds a community, linking people through shared attachments and ideas of home, bringing them together in times of change, stress, or even disaster. This was the case in Boscastle, Cornwall, as people responded to socio-environmental pressures on housing, fishing, and flooding. So too in New Orleans, where people say there’s no place like it, where a man said:

“If another catastrophe happened, worse than Katrina, the only thing I’m gonna do is leave. But then I’m gonna come back and rebuild my house. Because I love my area. It’s worth saving.”

Where resilience is about rootedness, then for me it is about soul; it is about the intangible sense of a deeper significance, almost spiritual or animist, that inheres in people, places, things.

Resourcefulness – the head or the hands of resilience

Prof Katrina Brown adds a third component to her vision of resilience: resourcefulness, which one might also describe as capability. Resourcefulness goes beyond resource access, and moves further than assessment of the state of individual or community assets, which tends towards a reductionist and economistic view of resilience. Resourcefulness is about the ability to overcome challenges and difficult situations, which brings attention to people’s qualities, characteristics, and agency. These are the decisions and crafts performed by the head and the hands of resilience.

While ‘resourcefulness’ helps Prof Brown with the alliteration of a triple-R, the concept of capability might be more effective here. Resourcefulness aligns rather too closely with ideas of entrepreneurialism. Indeed, the example given in the lecture was about (small-)business decisions and the generation of money in an African context. Likewise, we can hear about resourcefulness for corporate leaders in the Harvard Business Review, where tips include ‘lean on your staff’ and ‘do more with less’. If the objective is to avoid neoliberal framings, resourcefulness might not be the right word. Capability, by contrast, respects agency and conjures a long lineage that links to important ideas of human development and distributive justice.

Theatre – the drama of resilience

Concerns aside, Prof Brown provided a human-centred and agency-centred view of resilience by which we can understand rapid changes and responses within dynamic socio-ecological systems. This was an embodied analysis, where the audience could sense people with hearts, heads, hands and a soul in distant locations acting as powerful, as resourceful, as rooted. Impressively, Prof Brown’s project is much more than academic analysis: it is also creative and theatrical.

Rather than just dealing with intellectual concerns, Prof Brown has brought resilience thinking to the cultural domain of community theatre, enacted as participatory drama, in Kenya and in Cornwall. The hope is that engaging on an emotional level may encourage transformational forms of change that can help people to deal positively with the challenges they face in particular places.

We were told of women holding the microphone in Kenya to discuss a fishing community’s changing relationships with the sea. The role-play deliberations and laughter of the theatre setting gave rise to women’s voices, as they asked for education for girls, in a place where females are not ordinarily heard. While in Cornwall, forum theatre deployed traditional song and verse, and local terms and language, to engage participants in emotions of empathy and grief. This activity helped people to come to terms with the devastation wrought by severe storms, and to renew a resolve for collective action.

In a similar fashion to Dr Joanne Jordan’s work, which has involved participatory theatre exploring the lived experience of climate change in Bangladesh, Prof Brown has provided a cultural means of exploring the difficult implications of profound change, looking towards transformative solutions, while giving voice to more typically marginalised and excluded people. That is the kind of resilience that I cannot feel cynical about; I left the lecture feeling altogether more optimistic and inspired.

Prof Katrina Brown and colleagues have an article accepted for a forthcoming (2017) special issue of Ecology and Society, which will also be entitled ‘The Drama of Resilience’. I, for one, plan on reading.