by Dr Gindo Tampubolon (Reader in Global Health, GDI) and Dr Elia Maggang (Honorary Fellow, Lincoln Theological Institute)

This year marks the mid-point of the decade and the global health initiative known as the UN Decade of Healthy Ageing. Led by the World Health Organization (WHO) in collaboration with other UN organisations, the Decade aims to improve the lives of older people, their families, and the communities in which they live. At the end of 2024, the WHO invited the University of Manchester’s Gindo Tampubolon and Elia Maggang to join a meeting of experts in life course and healthy ageing to examine progress towards such aims and advise on whether a mid-course correction is necessary.

The occasion prompted both academics to reflect on current evidence and the experiences of ageing in both high-income and developing countries.

In the past, we have investigated healthy ageing and cognitive ageing and mapped geriatric syndromes across England’s local governments. Our investigation has revealed critical inequalities. Health trajectories based on repeated measures of blood biomarkers over a decade in England show inequalities in healthy ageing trajectories along social class (Tampubolon 2015, 2016).

Furthermore, we drew a map of frailty, a clinical syndrome summarising blood measurements and performance measurements, such as grip strength. Among older people over 50 years in all 317 local governments in England, we showed inequalities in frailty along urban, rural, and coastal disparities (Sinclair et al 2022).

Evidence Feeding into Policy

Such research evidence has fed health policy in England, a high-income country. First, through regular reports produced by the Policy Research Unit on Healthy Ageing funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). Second, indirectly, through scientific articles that are then used in government documents. For example, the latest report from Professor Sir Chris Whitty as the Chief Medical Officer of England extensively discussed our map of the spatial disparity in frailty. Older English people living in rural and coastal areas are at a disadvantage in getting the care they need in time, risking the syndrome costing the country dearly (Whitty 2023).

In addition to policy reports and scientific articles, evidence also fed into policy through direct involvement in international health organisations, such as the recent meeting organised by the WHO. This adds a global dimension to the evidence on the experience of ageing worldwide.

If the social inequality of health trajectory or the spatial disparity in frailty is already visible in high-income countries, what is increasingly clear to the WHO is the imbalance between the experience and the evidence of healthy ageing around the world.

The older (65+) population in China alone, at 217 million, is more than double that of all European countries put together. But China is ageing five times more rapidly than France. In time, the rich countries got old before they got rich. For the rest, they will get old while not yet rich.

Experience and Evidence: An Imbalance

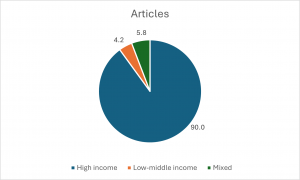

Yet most research evidence on ageing comes from the rich countries. To explore the imbalance between evidence and experience, we read the abstracts of all papers in the top three journals of gerontology and geriatrics in 2023, including Age and Ageing, the Journals of Gerontology (Series B Social and Psychological Science), and the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Together they publish research on healthy ageing and related topics. Out of 713 research articles, ninety percent focus solely on high-income countries, six percent on a mix of high and low-middle, and only four percent on low-middle-income countries. See the chart below.

Evidence of 713 research articles in top three journals of gerontology and geriatrics in 2023 by country focus (Age and Ageing, The Journals of Gerontology [Series B Social and Psychological Science] and the Journal of American Geriatrics Society) Source: Web of Science, Tampubolon and Maggang, Dec 2024

Action is needed to redress the imbalance between evidence and experience. This is because transferring the bulk of current evidence to explain healthy ageing experiences around the world falls short of good policy practice. For example, our recent article on ageing in China, focusing on the mental health of older people, strongly suggests that the historical experience of this population matters. Specifically, the victory of the communists against the nationalists in the country in 1949 matters for mental health and for physiological wear and tear sustained across the life course (also known as allostatic load) today (Li et al 2024a, 2024b). The historical event has led to selective mortality of the initial cohort and rendered the decades-long life course effect muted.

We call for mutual learning because older people around the world are participants in the initiatives to deliver health for all, including the UN Decade of Healthy Ageing.

Top image by RDNE Stock project.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Please feel free to use this post under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Full information is available here