By Aarti Krishnan and Dr Judith Krauss, PhD Researchers at the Global Development Institute

In an era when sustainability has become a buzzword, two key questions arise regarding sustainability standards in global production networks: what drivers underlie the adoption of sustainability standards, and what benefits do they entail for local producers? Looking at both Northern firms and Southern actors, we explore these questions through the cases of fresh fruit and vegetables in Kenya and cocoa in Nicaragua in a research project now published as a discussion paper by the United Nations Forum on Sustainability Standards.

Despite the countries being 8,500 miles apart and farming very different crops, we found considerable parallels between Kenya and Nicaragua: the cocoa and fruit and vegetable markets are primarily buyer-driven and Northern firms delineate what needs to be done to be ‘sustainable’, while grassroots actors (such as farmers) have lower agency and less space to negotiate the terms of sustainability. Different private-sector, public-sector and civil-society stakeholders hold different priorities: their commercial, socio-economic and environmental drivers were so varied as to be partly incommensurable. Lead firms’ push for traceability so as to safeguard food safety for consumers in the Global North took priority over communities’ interests in terms of safeguarding the long-term environmental viability of their cultivation and their socio-economic livelihoods.

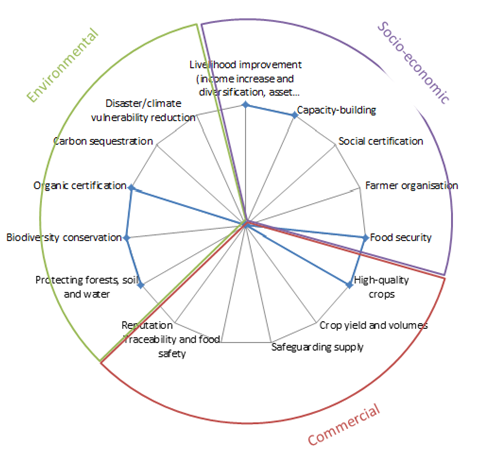

We used a ‘constellations of priorities’ model based on drivers shared by our stakeholders to systematically analyse the motivations contributed by the stakeholders, extending the scope of analysis beyond the oft-investigated lead firms to cooperatives and smallholders, so as to emphasise the agency of the latter.

So what do these asymmetrical priorities in production networks mean for smallholder farmers? Reasons underlying the adoption of sustainability standards are often framed suggesting that performing upgrades required within sustainability standards translates automatically into positive benefits for all actors involved. Literature distinguishes three types of upgrading: (1) social upgrading entailing empowerment benefits for smallholders and workers, (2) economic upgrading providing fiscal and commercial advantages, and (3) environmental upgrading, which concerns ecological advances. Our research endeavoured to unearth the extent to which upgrading economically, socially and environmentally could create local benefits for cooperatives and smallholders?

Distilling the insights from the two case-studies, the priorities of Northern private-sector stakeholders were palpable across the initiatives, with their corporate power helping them to imprint and project their drivers over and above other stakeholders’ priorities. This marked power asymmetry demonstrated that Southern communities’ interests were often overshadowed; for instance local value capture from certifications was low because the economic costs outweighed the price-premium gained by selling to Northern markets. This also questions the assumption that adopting sustainability standards automatically empowers farmers. It appears the private sector is motivated by consumer concerns in the North that prompt the proliferation of standards rather than understanding to what extent these seals have actually led to positive developments amongst those who need to comply with them.

“I do not know many of these sustainability standards, never mind what they mean. But if I buy something more expensive, I want farmers to benefit.” Responsive consumer, Europe

This poses a question – what is sustainable? The answer to that question is quite complex. Northern private firms need to negotiate markets, consumers and stringent public regulation, while Southern actors desire resilient livelihoods and environmentally viable local development. Overlaying power dynamics with divergent priorities suggests there will always be winners and losers, with Southern actors capturing less value, economically, socially and environmentally. But for how long can private firms from the Global North continue to impose their priorities? The ‘constellations of priorities’ model is a viable framework to systematise an analysis of the drivers of diverse stakeholders, providing agency to each stakeholder. This can be used to map the different dimensions across which priorities can converge to create win-win solutions. Ultimately, adopting a sustainability standard should lead to positive outcomes for all, leaving no one behind.

The full paper is available from the United Nations Framework for Sustainability Standards discussion paper series, with a Power Point summary available from here. All feedback most welcome! judith.e.krauss@gmail.com; aarti.krishnan-2@manchester.ac.uk