by Dr Gindo Tampubolon, Reader in Global Health

A series of six scientific assessments by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports with increasing confidence that global warming poses major risks to the earth and its people. What is equally clear is millions of people do not trust the fact.

The assessments have been diligent in documenting and refining the consequences of global warming to nations and citizens, their well-being, livelihoods and health. Heat exhaustion, for instance, puts older adults at risk of heart failure, while increased awareness of climate change has been linked to a rise in common mental health issues such as anxiety.

However, nations vary in their exposure to the risks with some places even gaining increased agricultural productivity. Nations vary in their vulnerability.

I use a report on personal anxiety from 113,000 teenagers and adults aged over 15 in 108 countries in 2020 to examine whether there is significant variation in rates of anxiety and whether this relates to trust in science. Specifically, before being asked about trust, they were informed that a working definition of science is ‘the understanding we have about the world from observation and testing, by people who study Planet Earth, nature and medicine among other things.’

Perhaps trust in science correlates with personal mental health, irrespective of personal attributes such as incomes. People who trust that there are major risks may be more anxious than those who distrust the science. This is especially true given the scientific consensus that an effective response to global warming requires worldwide systemic change that extends far beyond adapting individual habits.

Materials

My source is the latest Wellcome Global Monitor report, which I have used in previous research to examine the relation between inequality and trust in science. Now, I turn my attention to links between anxiety levels and trust in the scientific fact that global warming is a major risk. The anxiety question was devised by a team of experts from around the world, including the World Health Organization, while the trust question has had a precedent. Again, the question about anxiety was prefaced by a working definition that ‘extreme anxiety or depression means a person being so anxious or depressed that they could not continue with their regular daily activities as they normally would for two weeks or longer.’ This elicited a yes/no response.

I enrich this source with national vulnerability to global warming risks, an index for each nation produced by the German Institute of Labor Economics or IZA. Other attributes include gender, education and incomes, allowing us to answer questions such as “given similar attributes such as incomes or literacy, to what extent does an individual’s trust in science affect their levels of anxiety?”

I applied multilevel models to understand people’s anxiety levels in the context of the vulnerability of their country of residence to climate risks.

Results

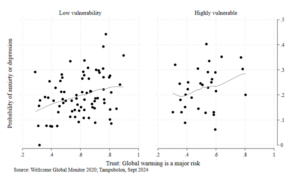

I begin by plotting (the averages of) anxiety on trust in the scientific fact; split at the median into low (left plot) and high vulnerability (right plot) nations (Figure 1). The trellis plot shows that in all nations more trust in the scientific fact correlates with higher anxiety. Moreover, in highly vulnerable nations, this relation is shifted and tilted upwards. For the same average trust, adults in vulnerable countries are more anxious (compare trust at 0.6). Then, for the same amount of increase in trust, adults in vulnerable countries get more anxious by a higher amount (compare as one moves horizontally from 0.4 to 0.8, the attendant vertical shift is larger in highly vulnerable countries). This hints at a complex interaction, warning against ignoring the distinction across country vulnerability.

Figure 1. Country correlations between anxiety and trust in science that global warming poses major risks; countries are distinguished along vulnerability level s – from 113,460 adults aged over 15 in 108 countries.

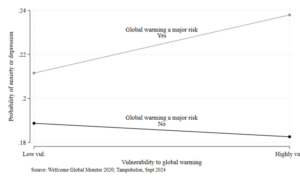

Furthermore, the data reveal a novel insight, once subjected to modelling to explain the probability of anxiety in terms of trust that global warming poses major risks. I plot below the predicted probabilities of personal anxiety and trace those who trust separate from those who distrust, and compare people in nations highly vulnerable to the risks and in nations low in vulnerability (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Marginal plots of probabilities of personal anxiety for combination of trust or distrust in the science, and the context of nations (vulnerable or not); controlling for age, gender, education, income and employment status – 113,460 adults aged over 15 in 108 countries.

The nearly flat bottom line shows the probabilities for adults who distrust the science, disagreeing with the statement that global warming poses major risks. Adults who dissent from global warming being a major risk show only tiny differences in probability of anxiety irrespective of where they live, whether in highly vulnerable places or not. Adults with a different belief from the scientific fact are hardly influenced by their context. It makes no difference to them whether their nations are highly or less vulnerable to global warming consequences. Their national vulnerability does not influence their personal anxiety.

The top line, climbing north-eastward, shows the probabilities of anxiety or depression for adults who trust the scientific fact that global warming poses major risks. Importantly, they are susceptible to the context of the nation where they live. Their national vulnerability influences their personal anxiety – so much so that the bottom and top lines form a clear, sharp wedge. Adults who trust the scientific fact of the risks of global warming report higher probabilities of being anxious to begin with (in less vulnerable places). But if they live in places highly vulnerable to global warming risks, their probabilities increased even more. The result is in highly vulnerable nations, there is a wide chasm in the associations between the scientific fact and anxiety.

This interaction has never been shown before – that is, under global warming the contextual and personal factors interact in complex ways to drive personal anxiety. The magnitude of the interaction is also remarkable: it doubles the initial difference in probabilities of anxiety between those who trust and distrust that global warming poses major risks.

A counsel of despair?

At first glance, this result poses an inconvenient message. Adults distrusting the science are less anxious throughout, irrespective of whether their context is highly vulnerable. For the sake of better mental health, distrusting science is convenient – the bottom line suggests. This is clearly a counsel of despair.

The wedge, not just the bottom line, points to a better alternative. Even among adults who trust that global warming poses major risks, low levels of nation vulnerability go with better mental health. Therein lies hope. Improving country responses to mitigate and adapt to climate change, thus reducing nation vulnerability, could nurture better mental health for all citizens. This of course requires effective global responses such as those related to loss and damage.

Granted, this does not promise to eliminate the difference in anxiety between the top and bottom lines. After all, the stock of greenhouse gases has been accumulating in the atmosphere since the industrial revolution and it is the stock not the flow which determines the risks today. Moreover, personal mental health is driven by more than what I consider here. In sum, the data say that global action designed to reduce nation vulnerability, e.g. by helping developing nations to adapt, mitigate and receive compensation, holds a promise of better mental health all round.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Please feel free to use this post under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Full information is available here.

Photo by Malcolm Lightbody on Unsplash