Barnaby Joseph Dye, University of Manchester

Ghana reformed its electricity sector by the book but has lurched from blackouts between 2012 and 2015 to a glut of energy which costs government about 5% of GDP. Fitch ranks the energy sector as the biggest driver of national debt. How did this happen? It’s a classic case of implementing the “standard reform model” – a one-size-fits-all approach – that ignores a country’s political realities.

Ghana is not alone in reforming its electricity sector as it was a key requirement of the “good governance agenda” of the 1990s, nor is it the only country where reforms have caused crises. Rwanda and Mozambique are other examples.

The governance agenda pushed by multilateral development institutions such as the World Bank had a number of pillars on which the reform of the electricity sector rested.

They included:

- independent regulation

- transparent tariff setting

- independent power producers

- splitting a utility into independent generation, transmission and distribution entities.

The case for these reforms was that competition and the “right” institutions would create efficiency and allocate capital effectively. Ultimately it would bring down power production costs while meeting the needs of consumers.

Ghana introduced independent power producers in 1998, adding to its state-owned utilities. It also created two regulatory bodies. They are the Energy Commission, which licenses independent power producers and advises government, and the Public Utilities Regulatory Commission, which approves power purchase agreements and sets tariffs.

But these mainstream “solutions” didn’t work. My recent paper looks into the reasons. I argue that the common political drivers behind the crises of under-supply and over-supply are under-appreciated, and that mainstream approaches to improving electricity policy made these crises worse. As the case of Ghana shows, the standard reform model can increase opportunities for distorting the electricity system.

Ghana’s power crises

Ghana’s move from blackouts to a financial crisis caused by too much power can be traced back to 27 August 2012, when a small group of pirates triggered the first of two major power crises in the country.

Attempting to escape from the Togolese navy on a captured oil tanker, the pirates left the ship’s anchor trailing. It snagged on the West African Gas Pipeline, which transports Nigerian gas to Togo, Benin and Ghana. This sparked a major fuel shortage, which combined with drought to plunge the country into four years of electricity shortage and frequent grid shutdowns.

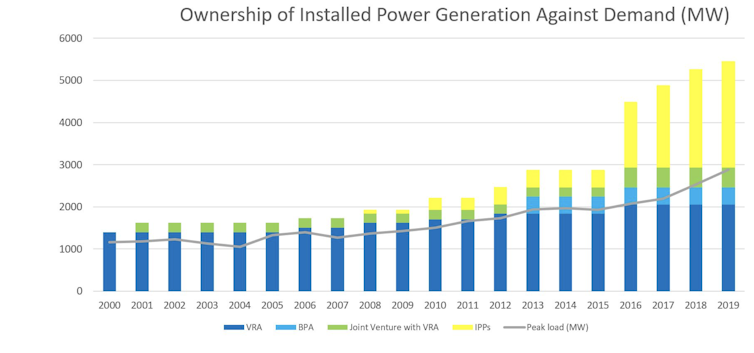

This crisis of shortage was quickly replaced with one of overabundance. Ghana went into a power plant construction overdrive, resulting in generation capacity equalling twice the country’s demand by 2018. The installed capacity, according to the Energy Commission of Ghana, is 5,083MW, almost double the peak demand of 2,700MW.

This increase in generation capacity came from take-or-pay contracts. The government’s distribution utility must pay private electricity companies typically for 90% of the power they make available, regardless of whether it is used. Ghana’s large imbalances in supply and demand leave the utility with a hefty bill, reaching an annual deficit of US$1 billion. Ghana’s has renegotiated power purchase agreements with six of the independent power producers, a deal that the Minister of Finance Ken Ofori-Atta says will save government US$13.2 billion over the duration of the agreements.

Political competition

The break in the gas pipeline was an immediate trigger. But it was fixed by 2014.

The length and depth of Ghana’s shortage crisis can only be explained by “following the money” and the political drivers behind Ghana’s fiscal issues.

Ghana has two dominant political traditions that have contested power since independence. They are now aligned under the New Patriotic Party and National Democratic Congress. Competition between the two is fierce in Ghana’s swing regions. There’s also competition within each party, resulting in regular reshuffling of senior figures.

These political struggles are expensive, requiring the distribution of benefits to supporters and the employment of numerous party foot-soldiers. Back in 2016, researchers found that MPs on average needed GH₵389,803 (about US$85,000) to contest elections and these costs will have increased since then. Such costs encourage corrupt deal making and more legitimate rent seeking that benefits affiliated companies and donors. Equally, politicians feel they must back popular policies, such as low electricity tariffs, and ensure government programmes like electrification are targeted at supporters.

Ghana’s power cuts came because the government and state utilities did not buy alternative imported light crude fuel and gas. That fuel could not be bought because of the national budget deficit in 2012 following that year’s election. Additionally, the governments of the National Democratic Congress and the New Patriotic Party have intervened to lower tariffs, or prevent their increase, despite the process being officially independent.

The intensity of party-political competition also partly explains the oversupply financial crisis. In the run up to the 2016 election, power shortages were continuing and the government seemingly panicked, signing 32 private-sector power generation contracts. To do this, it overrode the role the experts, regulators and semi-independent utilities are supposed to play in planning electricity generation.

On top of this electoral pressure was the role of ideology. The increase in electricity was justified on the assumption that it would translate into industrialisation and growth. The business environment, structural barriers and international competition were disregarded.

The result is that Ghana has to pay for power it can’t sell, plunging the energy utilities into debt.

Misplaced mainstream solutions

Mainstream prescriptions for solving such electricity crises do not appear to address these political drivers. If anything, they exacerbate them.

In Ghana, independent tariff setting and the procurement of power from private companies did not follow the official market logic or legal rules on the separation of political power. Political incentives, electoral pressures and ideological instincts overwhelmed such formal structures.

Market-based reforms made the crisis worse, enabling rapid procurement of private plants and the bypassing of expert planning. The oversupply crisis would almost certainly have been impossible without private-sector procurement.

It’s therefore necessary to abandon the assumption that market logic, privatisation and formal regulation provide the best answers to electricity sector crises.

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.