To what extent are occupations shaped by the family’s educational record?

In early 2018 we published a blog called Bangladesh and Education: doing well, could do better. It was based on late 2017 data from the Hrishipara Daily Financial Diaries project, which has been tracking the lives of 70 low-income households in central Bangladesh since May 2015.

Today we return to the theme, partly to take advantage of a further two years of data, and partly to extend the discussion to look at the educational histories of households, and how that relates to the occupations of its current members.

More years in school

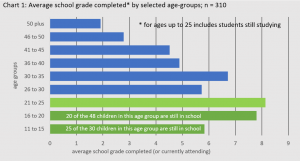

A chart in the earlier blog showed that teenagers in late 2017 were staying in school for very much longer than their parents had. For another view of that phenomenon, Chart 1 takes 310 family members of our current crop of 60 ‘diarists’, divided into 5-year-long age-cohorts, and shows the average school grade reached by the members of each cohort (by ‘family’ we mean members of the diarists’ households, and siblings about whom we have reliable information even though they no longer live in the household).

People now aged 46 or more were of primary-school age in or before the 1970s, the time of Bangladesh’s bitter war of independence, when the education system was in tatters. Grade completions improve with the next generation, but the really spectacular gains are made by those reaching their school years in this century. Youngsters between 11 and 15 years of age have on average already reached grade 6 and five out of each six of them are still in school.

Did you go to school, grandma?

We can also look at how grade-completion runs within families. Table 1 shows how having better-schooled grandparents and parents is associated, in our sample at least, with achieving higher grades. But these days having unschooled grandparents or parents does not debar someone from attending school: even people whose grandparents and parents were unschooled reached, or are studying in, grade 5.

Table 1: grade completed (or currently studied) by schooling of parents and grandparents

| Of 310 people over the age of 10: | average grade reached: |

| 46 people whose parents studied beyond primary level | 9.1 |

| 41 people whose grandparents had some schooling | 8.9 |

| 85 people whose parents had some schooling | 8.2 |

| 123 people whose grandparents never went to school | 6.3 |

| 85 people whose grandparents and parents never went to school | 5.1 |

| 149 people whose parents never went to school | 4.7 |

Schooling and occupations

How do family educational histories relate to occupations? We looked at three possible measures. First, is better grade-achievement among the ‘grandparent generation’ (the parents of the currently economically active family members) associated with families that follow more desirable current occupations? Second, how closely are the grade-completions of those currently active members associated with the desirability of the occupations they are following? Thirdly, are the youngsters of families with the more desirable occupations reaching higher grades at school?

To rank occupations, we avoided ready-made categories. Instead, we convened a small panel of local people and asked them to consider occupations and mixes of occupation typical of our diarist households and rank them by desirability. We left the panel to decide what constitutes desirability. Table 3 summarises their views, identifying five groups of occupation-types, by level of desirability.

Table 3: groups of occupation-types ranked by local measures of desirability

| Group | Occupation/income sources | Examples |

| Most desirable | Remittances; religious occupations; salaried and government employment; white-collar employment | Having a family member regularly remitting from overseas; Imam; farming one’s own land; medium-scale restaurant proprietor; schoolteacher |

| 2 | Other occupations with reliable regular income, especially if supplemented by remittances | Having a family member employed overseas; hospital orderly; established trader (saris, cattle); well-stocked single-proprietor shop; ATM guard; travelling tobacco salesman |

| 3 | Other kinds of reliable employment or self-employment | Motor or sanitation mechanic; skilled construction labour; driving one’s own e-rickshaw; bus driver |

| 4 | Skilled casual employment or self-employment | Barber (own premises); garbage recycler; bamboo craftsperson; cook |

| 5 | Part-skilled casual employment or self-employment (often ‘low caste’) | Shoe-repair; barber; boatman; fisher; TBA |

| Least desirable | Casual unskilled irregular employment or unemployment | Helping at market stalls; casual domestic labour; farm day labour; brick-breaking; unemployed |

The older generation and occupations

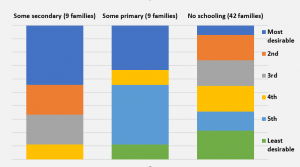

We first divided our 60 diarist families into three groups, based on the best school grade reached by anyone in the ‘grandparent generation’ (the parents of the currently economically active family members). Chart 3 shows the desirability of the occupations found in each group. This generation was largely unschooled, so the samples for the schooled ones are small. Nevertheless, none of the 9 families whose grandparents had some secondary education follow any of the two least desirable categories of occupation, and almost half of them follow the most desirable. But where there was no schooling only two families have the most desirable jobs. One of these families is a couple where both of them are government hospital messengers and enjoy regular salaries, bonuses, and a chance to earn tips. The other is a particularly entrepreneurial woman who trades saris, rears cows, and gets remittances from sons overseas.

We first divided our 60 diarist families into three groups, based on the best school grade reached by anyone in the ‘grandparent generation’ (the parents of the currently economically active family members). Chart 3 shows the desirability of the occupations found in each group. This generation was largely unschooled, so the samples for the schooled ones are small. Nevertheless, none of the 9 families whose grandparents had some secondary education follow any of the two least desirable categories of occupation, and almost half of them follow the most desirable. But where there was no schooling only two families have the most desirable jobs. One of these families is a couple where both of them are government hospital messengers and enjoy regular salaries, bonuses, and a chance to earn tips. The other is a particularly entrepreneurial woman who trades saris, rears cows, and gets remittances from sons overseas.

The income earners

The income earners

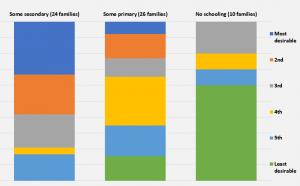

For Chart 3 we ran a similar analysis, this time focusing on the average school grade achievements of currently economically active adults over 15 years old.

As expected, the association between schooling and occupations is stronger for this group. The sample of families where none of the active adults are schooled is small, but more than half of them have the least desirable jobs (mostly in casual labour) and none has reached the upper two levels of desirability. By contrast, the secondary-school level families don’t work in the least desirable jobs, and they dominate the most desirable category, where regular remittance income from family members working overseas is common. As the foot of the first column shows, there are better-schooled families with unattractive jobs, such as one rather submissive man who, though he reached secondary school, works as a waiter in a tea-stall.

Occupations and the grades achieved by today’s youngsters

Occupations and the grades achieved by today’s youngsters

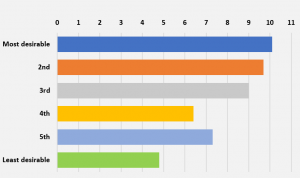

We saw in Table 1 that the more schooling parents have, the more schooling their children get, and in Chart 3 that people with more schooling hold more desirable jobs. It might follow that children in families with more desirable occupations reach higher school grades before quitting school. We checked that assumption by looking at today’s youngsters up to the age of 20 who have already left school, to see how the grades they reached line up against the occupations followed by their parents. Chart 4 suggests that the assumption holds. Note that children currently still in school are not represented in this chart, and in their case, the families with the least desirable occupations may be catching up somewhat.

Incomes and occupations

Incomes and occupations

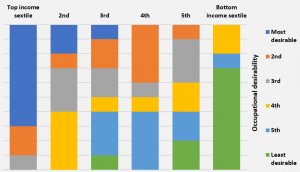

When the panel ranked occupations for us they didn’t focus exclusively on incomes. They also thought about respectability, about white-collar versus blue-collar, about the employer (the government evidently ranked high), and it seems they thought highly of regular income from family members overseas. To see the effects of this, we mapped occupational desirability against income, using six ‘income sextiles’ derived from our complete records of all transactions made by the households in the year to end September 2019. The results are shown in our final chart, Chart 5, and we show the incomes in Table 4. If it was the case that the desirability of occupations was determined wholly by the incomes produced, then we would expect to see, in Chart 5, that the column on the left (the families with the highest incomes) would be wholly dark-blue, signifying that they all have the most desirable occupations: and the right-hand column would be wholly light green. In fact, there is considerable mismatching. Several families with jobs only 4th -ranked for desirability, for example, get incomes in the second-highest sextile. They work in sectors like the construction trades and driving the new battery-driven rickshaws where wage growth has been strong recently: but these jobs are still not seen as very desirable.

Table 4: the six ‘income sextiles’, using income in the year October 2018 to September 2019 International $s (US$ at a rate that recognises that $1 buys more in Bangladesh than in the USA)

| Highest income sextile | 10 households with a median income of $10.92 per person per day: we describe them as ‘near poor’ |

| 2nd income sextile | 10 households with a median income of $4.21 per person per day: we describe them as ‘upper poor’ |

| 3rd income sextile | 10 households with a median income of $3.61 per person per day: we describe them as ‘medium poor’ |

| 4th income sextile | 10 households with a median income of $2.91 per person per day: we describe them as ‘poor’ |

| 5th income sextile | 10 households with a median income of $2.30 per person per day: we describe them as ‘very poor’ |

| Lowest income sextile | 10 households with a median income of $1.37 per person per day: with incomes of less than $1.90 pp pd they can be described as ‘extreme poor’ using World Bank guidelines |

Conclusions

The school grades that our diarist family members achieve is related to the grades their grandparents and parents reached. In various ways, school grade achievement is positively associated with the desirability of the occupations followed by our families. In the eyes of local people, the desirability of a job is determined only in part by the income it produces: other aspects also play a part.

None of these findings are startling, but the Hrishipara diaries provide us with a rare opportunity to present concrete evidence for them, anchored in the context of the real lives of low-income households over an extended period of time and researched day-by-day in extreme detail.

The headline news remains that school-grade achievement is advancing extremely rapidly and the generation born in this century are set to spend much longer in school than their parents and grandparents. The bet that families are placing by putting their children through more and more years of schooling may be paying off.

All fieldwork for the Hrishipara Daily Diaries Project is now being funded by L-IFT. We gratefully acknowledge their invaluable support

All fieldwork for the Hrishipara Daily Diaries Project is now being funded by L-IFT. We gratefully acknowledge their invaluable support

Stuart Rutherford

November 2019

Read more analysis based on the Hrishipara Diaries:

- Hrishipara daily financial diaries: Tracking transactions, understanding lives part 1

- How are Digital Financial Services used by poor people in Bangladesh?

- What the poor spend on health care?

- How the poor borrow?

- What do poor households spend their money on?

- Tracking the savings of poor households

- When poor households spend big

- When poor households spend big part 2

- Poverty measurement using data from the Hrishipara daily financial diaries

- Receiving Gifts in Low-Income Households

- Managing income volatility