Since May 2015 we have been conducting a ‘financial diary’ research project in central Bangladesh in which we record, each day, all the transactions made that day by our ‘diarists’ (as we call our volunteer respondents). You can read more about the project on its website here. In this blog we explore the role of gifts in the households of our diarists.

Gifts received from outside the household

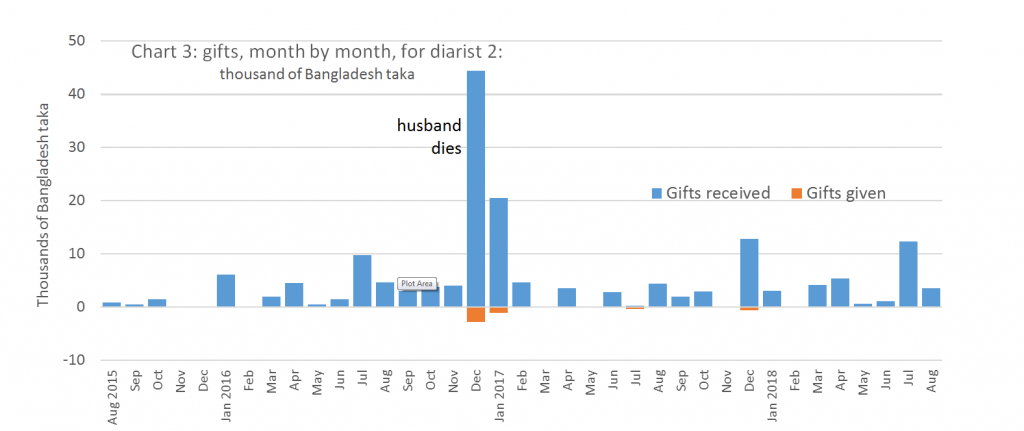

We have recorded just over a thousand transactions in which a diarist household has received a money gift from someone outside the household. This is a tiny fraction of the more than half a million transactions we have recorded, but the total value of these gifts is not negligible. You can get an idea of their scale relative to the economies of the receiving households in Chart 1, which shows the gifts our 72 diarists have ever received[1] as a proportion of their total income[2].

We have recorded just over a thousand transactions in which a diarist household has received a money gift from someone outside the household. This is a tiny fraction of the more than half a million transactions we have recorded, but the total value of these gifts is not negligible. You can get an idea of their scale relative to the economies of the receiving households in Chart 1, which shows the gifts our 72 diarists have ever received[1] as a proportion of their total income[2].

The total value of the gifts shown in the chart is 1.7 million Bangladeshi taka, or about $53,000 at Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) rates (which allow for the fact that a dollar buys more in Bangladesh than it does in the US). A thousand transactions over more than three years, amounting to more than $50,000 in value, provide enough data for us to start exploring the place of these gifts in the households of our diarists.

Taking all 72 diarists as a group, just over 5% of their income is composed of gifts, but as the chart shows the percentage varies sharply among the diarists, with some getting no gifts at all. In this blog we’ll look at who does the giving, and at how and when these gifts arrive. We’ll also look at what kinds of households are associated with high and low levels of receiving gifts and, perhaps most interestingly, at the impact they make on some of the recipients.

Who gives?

Who gives?

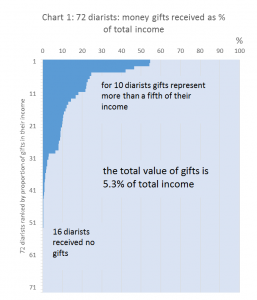

Chart 2 gives a breakdown of the sources of the money gifts we observed, by the total value of each category of giver. The importance of family links is very apparent: about three-quarters of all gifts, by value, are from family. Of these, the bigger share is from the wider family (cousins, in-laws, and the like) who contribute about twice as much as immediate family (parents, children and siblings). This suggests that low-income families often tap into the resources of better-off relatives, and our data broadly confirm this. Some of these gifts are given as general support to the recipient, and some for specific needs such as life-cycle crises like birth, death, marriage and ill-health.

Less than a quarter of all gifts come from outside the family, and their biggest sub-category is gifts from the general public, in which we include most religiously-based giving of alms, but also community contributions to events like marriages, funerals or prayer-meetings.

Trickles and bursts

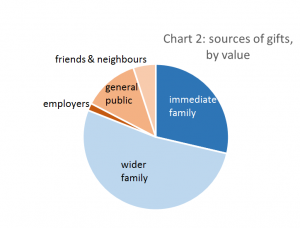

Alms-giving is associated with religious festivals, especially Durga Puja among the Hindus and the two Eids among the Muslims, and this gives rise to sharp seasonal peaks in this source of giving. No such seasonal rhythm can be seen in the data for the other forms of giving. At the level of the individual receiving household, gifts may trickle in as families seek to support the daily lives of those they give to, or may peak as crises occur. The case of the second-ranked diarist in Chart 1, whose gifts made up 54% of her income, is shown in Chart 3

Diarist 2, who we’ll call Shapla, is a woman in her mid 40s who breaks bricks by hand for a living[3]. She was widowed in December 2016: her husband had been a fisherman but had been sick and unable to work for many years. Both she and her husband were illiterate, but they put all five of their daughters into school, and four of them are now married and frequently give their mother cash gifts to help her raise the fifth daughter, now in high school. When her husband died the daughters increased their giving, but the local community also stepped in quickly and effectively, so Shapla was able to cover all the funeral expenses. Indeed, she had a surplus, which she used to improve her home.

It is often observed that gift-giving is reciprocal, with an expectation that the recipient makes a return gift later, or perhaps has already made a gift. For that reason we have included in chart 3 the gifts that Shapla has made to others. She had made some small charitable contributions at the time of religious festivals in late 2015, but during the year leading up to her husband’s death, when she was in very difficult circumstances, she made no gifts at all. Then she gave a gift of 2,800 taka to the priest who conducted the funeral rites, and soon after that gave 1,000 taka to her daughter on the birth of her child. On the anniversary of the funeral she gave another 600 to the priest and plans to do so again this year. But her gifts out are tiny by comparison with what she has received, and maybe her token ‘reciprocity’ is enough to satisfy her benefactors, and perhaps in her situation she will not be expected to make bigger gifts unless her fortunes change dramatically.

Who gets and who doesn’t?

One might imagine that Shapla – middle-aged, poor, illiterate, widowed and subsisting on unskilled casual labour – is typical of the diarists who have gifts as a big component of their incomes. And yes, another four of the top ten gift-receivers are somewhat like Shapla: women heads-of-household, no longer young, who get gifts mostly from adult children and their spouses. But the other five in the top ten include the top-ranked one, a sharecropper who unsuccessfully farms land belonging to his brothers, who subsidise him with gifts. There’s another sharecropper and a small-scale farmer. At rank 4 is a couple who own a failing snack-shop and get by with the help of a doctor in Dhaka for whom the woman used to skivvy decades ago. At rank 9 is an Imam, whose gifts come from his congregation.

At the foot of chart 1 are sixteen diarists who received no gifts in the time we have known them. This is not necessarily because they are among our better-off diarists, though some of them are: three of them live on remittances from overseas and are seen by the neighbours as rich, for example. But 10 of the sixteen are very poor, living in households with incomes of less than PPP$1.90 a day, putting them in the ‘extreme poor’ category. Among them are three illiterate young men who have migrated into our area from poorer districts elsewhere, seeking work, and who send virtually all their earnings home to their village families. The other 7 extreme-poor diarists in this group are local people with extended families, and it isn’t clear to us why they don’t get gifts.

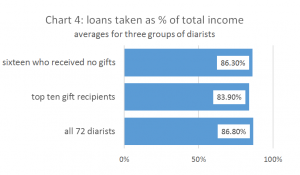

Borrowing can get you out of a problem, just as taking gifts can, so could it be that those who rely most on gifts are those that can’t get, or don’t want to take, loans? Shapla took only one tiny loan, and another of the top-ten took no loans at all. But others in the top ten took plentiful loans, and the same variation in loan-taking behaviour is true for the sixteen who took no loans. If we take the average values of loan taking, as Chart 4 does, we see that the value of loans taken (relative to income) is similar for gift-receivers and non-receivers alike.

Do these gifts help?

We assess the poverty-level of our diarists using various measures[4]. For example, we calculate daily per-person income and consumption levels, in PPP$ terms, and get numbers we can compare with standards like Bangladesh’s national poverty line, and the ‘$1.90 a day’ benchmark widely used in international comparisons as the upper limit for extreme poverty. About a quarter of our diarist households fall into the extreme poor category.

We assess the poverty-level of our diarists using various measures[4]. For example, we calculate daily per-person income and consumption levels, in PPP$ terms, and get numbers we can compare with standards like Bangladesh’s national poverty line, and the ‘$1.90 a day’ benchmark widely used in international comparisons as the upper limit for extreme poverty. About a quarter of our diarist households fall into the extreme poor category.

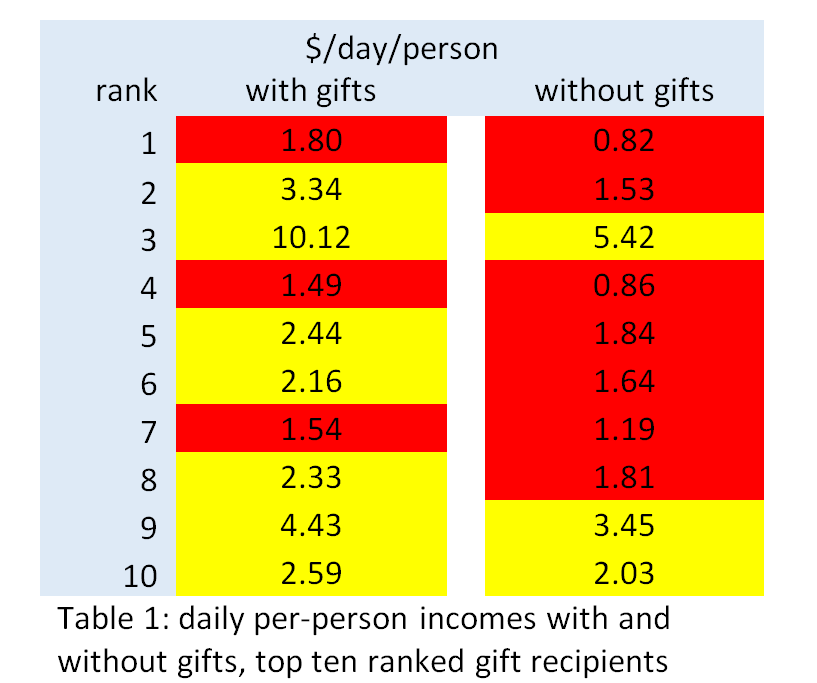

Among the top-ten ranked recipients of gifts, three are currently ranked as ‘extreme poor’, coloured red in the ‘with gifts’ column of Table 1. Were they not to have received those gifts, another four diarists would have joined them in the extreme poor category (and the already extreme-poor three would have plunged into abject poverty).

The simple ancient tradition of family and community-based help through cash gifts is an excellent and sustainable counter-poverty measure. Too bad it covers only a minority of our diarists.

References

- Diarists joined the project at different dates, and a small number have been dropped

- By income we mean inflows of money other than financial inflows (loans received and savings withdrawn): in the case of income earned from businesses we use the net income after deducting business costs from revenues (in our case, this principally means deducting the costs of buying stock from sales revenue).

- Bangladesh has almost no stone, so bricks are burnt and then broken to provide aggregate for concrete.

- See: Poverty measurement using data from the Hrishipara daily financial diaries

Stuart Rutherford,

October 2018

The Hrishipara Financial Diaries Project is currently being funded by the UNCDF SHIFT Programme based in Dhaka Bangladesh, and we are grateful for their support.

The Hrishipara Financial Diaries Project is currently being funded by the UNCDF SHIFT Programme based in Dhaka Bangladesh, and we are grateful for their support.

Read more analysis based on the Hrishipara Diaries:

- How are Digital Financial Services used by poor people in Bangladesh?

- What the poor spend on health care?

- How the poor borrow?

- What do poor households spend their money on?

- Tracking the savings of poor households

- When poor households spend big

- When poor households spend big part 2

- Poverty measurement using data from the Hrishipara daily financial diaries