The Hrishipara Daily Diaries project has been recording the daily money transactions of 70 low-income households in central Bangladesh, in some cases since May 2015. Bangladesh is famous for its microfinance banks (MFIs) and most of our ‘diarists’ have accounts with MFIs, so it is perhaps no surprise that we have recorded them taking more than 8 million taka’s worth of loans from MFIs, the equivalent of about a quarter of a million dollars at the ‘Purchasing Power Parity’ (PPP) exchange rate. Please see our publications page for other blogs about how diarists take and use loans.

Less well known is the fact that low-income households lend as well as borrow, and in this blog we will look at the phenomenon in more detail.

The big picture

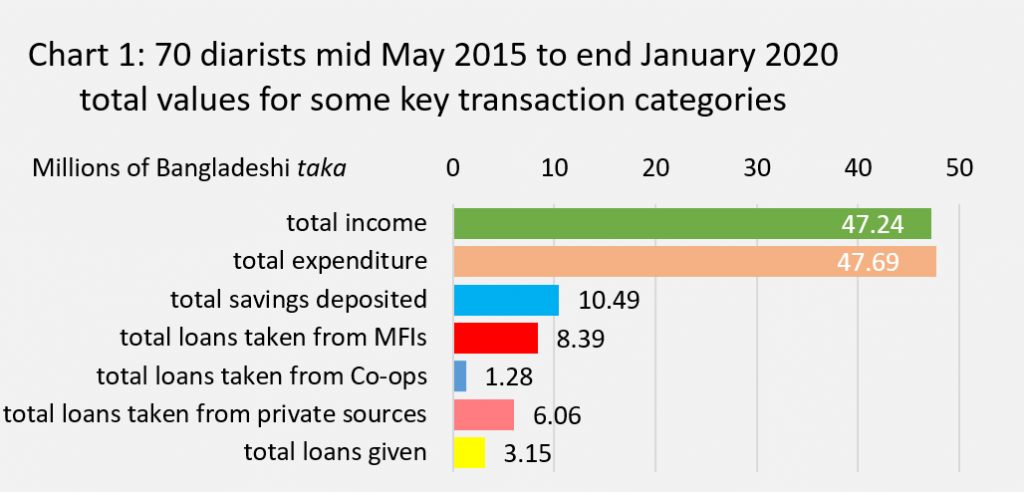

We begin, in Chart 1, with a comparison of some overall figures for the 70 diarists collectively for the period from mid-May 2015 to the end of January 2020.

Note: Diarists joined the project at dates between May 2015 and July 2017. Total income includes all earned income less business costs, including remittances from overseas and gifts. It does not include loans received or savings withdrawn. Private sources of loans include friends, family, colleagues, money-lenders and informal savings clubs.

Chart 1 places the diarists’ loans in the context of their total household economies. They deposited about 22% of their total incomes into savings accounts. This was more than they borrowed from MFIs (which was about 18% of income), but diarists also borrowed from Co-operative Societies and from private sources, so altogether they borrowed the equivalent of one-third of their total incomes. At the same time, they lent sums equivalent to almost 7% of total incomes, or more than one-third of the value of their loans from MFIs.

Note: In this blog, we will not examine the repayment of these loans nor the withdrawal of savings except to note that in total 16.8 million in loan repayments and interest were made on the total of 15.7 million borrowed; and diarists withdrew 10.3 million from their savings accounts.

How big are these loans?

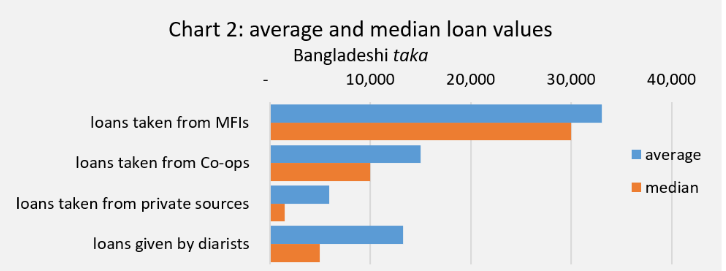

Chart 2 shows the values of the loans in the four categories. Ranked by loan size, whether as an average or a median, MFIs come top, followed by the Co-ops. The loans given by diarists are in third place, and the private loans they take fourth.

Showing both average and median values hints at the variability of loan values. The big and better-known MFIs (Grameen Bank, ASA, BRAC, and BURO) generally didn’t make small loans: a few loans of less than 10,000 taka (PPP$ 300) were issued by smaller MFIs, or by Grameen through its flexible ‘top-up loan’ system under which borrowers can refresh their loans before repaying them in full. The Co-ops are more willing to make smaller loans but don’t offer many bigger ones – they issued no loans above 40,000 taka in the period.

The values of informal loans – those given and those taken by our diarists – are quite different. There are a few big loans and a long tail of small and very small ones, some of them very small indeed. Our poorest diarist, for example, once gave a loan of just 10 taka (PPP 30 cents) to her nephew.

Note: So far, we haven’t recorded any repayment of the tiny loan to the nephew mentioned in the text. This alerts us to another important difference between private and MFI/Co-op loans: private loans are sometimes really gifts, disguised as loans to preserve the dignity of the recipient.

The borrowers and the lenders

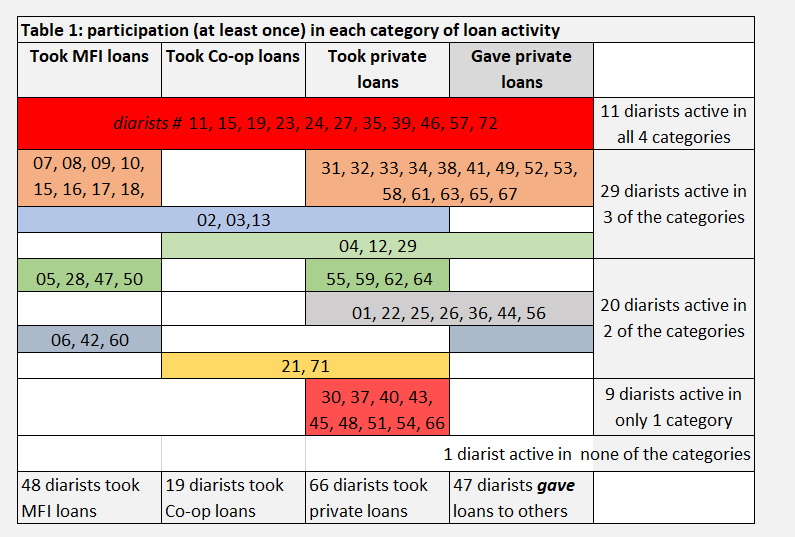

Who takes and gives all these loans? Table 1 explores.

Note: An astonishing 21 different MFIs serve our diarists. By contrast, there are only four Co-ops, and only two of them are reliable.

Big majorities of our 70 diarists borrow from MFIs and take and give private loans. More diarists borrow privately than take MFI loans but many do both. The nine diarists who were active in only one category took private (not MFI) loans. Almost as many diarists gave loans to others as took loans from MFIs: many did both. A majority of diarists were active in at least three of the categories.

Note: The categories are not as watertight as the table makes it seem. For example, more than half-a-million taka (PPP$ 15,000) in ‘loans from MFIs’ were ‘proxy loans’ – loans taken by our diarists not directly from the MFI but via an MFI client. Our diarists deliberately set this up, and the MFI loan went from the MFI via the ‘real’ borrower immediately to our diarist, so we categorise them as ‘MFI loans’ rather than private ones. In other loans, the money-trail is less clear and we have categorised them as ‘private loans’. Below, we also discuss cases where our diarists took MFI loans but immediately on-lent them to others.

Table 1 invites many questions, but in the remainder of this blog, we’ll focus on understanding who our diarists lend to, what kind of loans they give, and why they do it.

Who borrows from our diarists?

Table 1 shows that 47 of our diarists gave loans to others. By ‘others’ we mean people who are not members of the lender’s own household. This definition includes many close family members such as siblings and adult children living in other households, wider family members like cousins and in-laws, neighbours, work colleagues, and people with whom our diarists have business relationships. In virtually all cases the borrowers are known, usually well known, to the lenders. As lenders, our diarists are unlike the MFIs, who lend to any low-income household that accepts and respects the terms and conditions of their loans.

Low-cost loans

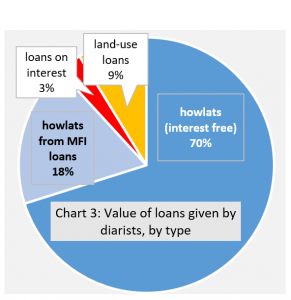

MFIs charge interest on their loans of around 26% a year with some, like Grameen Bank, somewhat cheaper. Diarists mostly lend in smaller amounts (chart 2, above) and you may have expected that their smaller loans would be given without charging interest. But this is true of most loans given by diarists, not just the smaller ones. As Chart 3 shows, most of the loans by value, as well as by number, were lent free of interest

Howlats (or dars) are interest-free loans. They don’t have fixed loan terms or repayment frequencies, but small ones are expected to be paid back quickly. They are the commonest form of informal lending all over Bangladesh.

Some howlats are sourced from MFI loans that the howlat-lenders take. Usually, the borrower agrees to repay the loan according to the strict weekly schedule imposed by the MFIs, and those repayments include the interest that the MFI charges. Borrowers sometimes make an additional payment, such as agreeing to pay some savings into the MFI customer’s MFI saving account along with the loan and interest payments.

Loans on interest comprise only 3% of the value. Some are traditional ‘paddy loans’ in which a borrower takes a loan to invest in farming and repays the principal along with an amount of paddy, at harvest time – though nowadays, as in most of our cases, they pay this interest in cash rather than paddy. Others are loans for businesses or urgent family matters and are charged interest by the month: often the asking rate is 5% or 10% a month though in practice most lenders settle for less.

Land-use loans, known as rehan or kot loans, are a traditional way of swapping cash for the right to farmland. The lender (our diarists in the cases we are discussing) makes a cash loan to a landowner. No interest is charged, but the lender has the right to farm the land until and unless the loan is repaid in full. The authorities discourage rehans, but they remain popular and can be of use to both parties. Borrowers prefer it to outright sale of land as a way to solve family emergencies as they can still hope to get their land back eventually. Lenders get access to farmland at less cost than buying it and without having to worry about paying rent.

Meet the lenders

Sketches of a few diarist lenders will illustrate the range of reasons why they lend, where the money comes from, and what the loans get used for.

Diarist 38 – we’ll call her Jasmin – is raising three children and has built a new house from remittances sent by her husband who works in a car-wash in Dubai. Remittances are the income source of the diarists who lend most money, and Jasmin has lent more than 108,000 taka (PPP$3,000). They are all howlats, the smallest 60 and the biggest 50,000 taka given to her sister’s husband to help him to get a job overseas. Most of the howlats went to relatives like him. Jasmin and her husband are from poor farming families but the Dubai job puts them now in the top income quartile of all our diarists, around PPP$10 per person per day. Watch the video to hear what she says.

Hossein, diarist 10, is illiterate and his household is in the lowest income quartile, earning less than PPP$2 a day per person (making them ‘extreme poor’ by World Bank calculations). He breaks bricks by hand (to make aggregate for concrete) and does faith-healing. He gives a few howlats but despite being poor also lends on interest. He makes ‘paddy loans’ (see the previous section) to a farming friend, and repeats the loan each year, successfully. Hossein, then, is a sort of moneylender, but his moneylending hardly constitutes an occupation. He does it with just one partner who likes having a reliable repeat lender with whom he feels on good terms.

Diarist 15, Izzat, is a tailor, and his household is in the second income quartile (upper-poor by Bangladeshi standards). He lends a bigger proportion of his income than any other diarist bar one. Most of his lending is related to his working status. He’s an independent tailor but lacks a good location to attract custom, so his sewing-machine is in a busy shop that sells lunghis (loin-cloths). Lunghis have to be sewn before they can be worn, so the shopkeeper likes having Izzat on hand as ‘his’ tailor, and doesn’t charge him rent for the space hE is using. But there is a well-understood pecking-order between the two men, so when the shop-keeper asks Izzat for howlats, Izzat feels obliged to lend. To fund these howlats Izzat borrows from an MFI – but doesn’t pass on the interest cost to the shopkeeper. The shopkeeper repays the howlats (which he uses to pay his shop rent) in daily sums of 200 taka. Izzat tolerates the arrangement, though it does put him in the odd position that, despite being one of our biggest diarist lenders, he lends at a loss.

The elderly Asraf (diarist 19) is a farmer who has recently opened a small restaurant in the market. His is a very large three-generational household and over the years we have tracked a wide variety of their borrowing, saving and lending. When he lends he does so with a very clear purpose: to strengthen his wider family through land ownership. This is why he gave his brother-in-law a large howlat to help him buy farmland.

In short

Most of our 70 diarists lend as well as borrow. Diarist households with income from jobs overseas are among those who lend the biggest amounts, but diarists from all levels of income lend and are among those who lend most as a proportion of their income. They may lend from their own savings, or from loans that they take from MFIs and then on-lend to others. Though some make loans on interest none of them lends as a business – they are not ‘moneylenders’ in the sense of people who derive a living from lending. A big majority of the money they lend is lent interest-free. They lend small-to-medium amounts of money in interest-free ‘howlats’ to their family, friends and neighbours and these loans may be used for any number of purposes. But most of their bigger loans are directed at strengthening family economies – so they go to cousins or nephews to help them get jobs overseas, or to brothers or in-laws to buy or lease-in land for cultivation or to start or maintain a business. Such loans form an important part of their strategies for family development.

Stuart Rutherford

February 2020

still photographs by the author; videos by Kalimullah and Shamol

with thanks to the diarists for their patience: their names are disguised

All fieldwork for the Hrishipara Daily Diaries Project is now being funded by L-IFT. We gratefully acknowledge their invaluable support.

All fieldwork for the Hrishipara Daily Diaries Project is now being funded by L-IFT. We gratefully acknowledge their invaluable support.