by Jules Buckland, student in PPE

While the Labour government has committed an initial £1.8 billion to its flagship Warm Homes Plan, this policy offers little in the way of transformation, largely expanding upon mechanisms used over the last decade (such as the Energy Company Obligation and Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund). While previous and current efforts to improve the insulation of UK housing stock are often justified by projected health benefits, my analysis of that historical data suggests that without a change in strategy, new funding may fail to deliver in this respect.

Officially, the primary objectives of the government’s new Warm Homes: Local Grant are to tackle fuel poverty and deliver progress towards Net Zero 2050. This marks a significant departure from the 2021 Sustainable Warmth Strategy, which explicitly listed ‘health and well-being’ as a core vision and a primary outcome. In the new 2025 guidance, health has been demoted: it is no longer a numbered objective, but listed merely as a co-benefit that sits ‘alongside’ the leading goals of carbon and cost reduction. This policy shift reveals a critical blind spot. By prioritizing thermal efficiency, the policy relies on technical ventilation standards (PAS 2035) that mandate ventilation assessments. However, these standards often fail in practice when fuel-poor residents may block vents or seal draughts to conserve heat, creating a gap between modelled and actual indoor air quality.

Using a decade’s worth of Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) data, I calculated the average energy efficiency improvement for every Middle-layer Super Output Area (MSOA) in Greater Manchester. I then compared this to NHS data on hospital admissions for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), a severe respiratory illness often made worse by cold, damp living conditions.

The analysis produced an unexpected result: there was no statistically significant connection between the millions spent on insulation and any meaningful reduction in respiratory illness. While health benefits from housing upgrades may have a significant time lag, the complete absence of a trend suggests that current interventions are not merely delayed, but disconnected from the primary drivers of ill health.

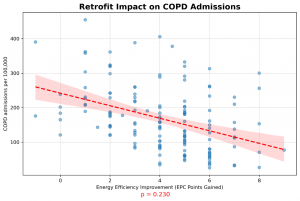

I visualized this using two graphs. When I plotted energy efficiency improvements against health outcomes, the result was a flatline—a scatter of noise with no significant upward or downward trend.

A scatter plot analysis of 151 Manchester neighbourhoods reveals no statistically significant relationship (p = 0.230) between energy efficiency gains (EPC points) and reductions in respiratory hospitalisations.

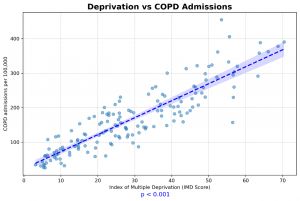

However, when I mapped COPD admissions against the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), a clear pattern appeared.

A scatter plot analysis of the same 151 neighbourhoods reveals a strong statistically significant correlation (p < 0.001) between deprivation (IMD Score) and respiratory hospitalisations, explaining 79% of the variation in health outcomes (adj. r2 = 0.788)

These graphs represent a statistical reality. Areas that saw significant energy efficiency improvements showed no corresponding drop in COPD admissions (statistically insignificant at p = 0.230). In contrast, an area’s level of deprivation explained a staggering 79% of the regional variation in respiratory illness.

Consider Harpurhey South & Monsall, where the median EPC is 71 (Band C). Despite meeting government standards, the area records 390 COPD admissions per 100,000—more than double the regional average. Its deprivation score is 70.4, placing it among the most deprived neighbourhoods in the dataset. This suggests the government’s plan was targeting the wrong variable. This raises an important question: why don’t these housing improvements translate into better health outcomes?

The government’s strategy assumed that retrofitting would directly lead to warmer homes and better health. However, the data from Greater Manchester suggests this mechanism is failing. Three factors appear to be responsible.

First, the policy relies on mismatched evidence. The core assumption draws heavily on the Warm Up New Zealand programme, cited as primary evidence in NICE Guideline NG6. However, that data was derived largely from uninsulated, timber-framed bungalows—a structural context vastly different from Manchester’s solid-brick terraces where moisture retention is a critical risk.

Second, fuel poverty means that residents often cannot afford the energy required to heat their newly insulated homes. A 2022 report by National Energy Action found that even in insulated properties, low-income households frequently ration heating to save money. If residents cannot afford to turn the heating on, the theoretical efficiency of the building fabric makes little difference to their immediate health outcomes.

Third, the policy ignores the well-established link between poverty-related stress and respiratory illness. The constant pressure of financial precarity is a significant non-environmental factor that impacts public health, a finding supported by numerous studies into the social determinants of health. The data suggests that these stressors are a much stronger predictor of poor health than the thermal efficiency of a building.

Of course, housing is not the sole determinant of respiratory health. The NHS has correctly identified respiratory disease as a clinical priority, channelling funding into Targeted Lung Health Checks and smoking cessation services as part of the NHS Long Term Plan. However, these medical interventions fight a losing battle if patients are discharged back into damp, mouldy environments. As the Marmot Review (10 Years On) emphasized, medical care accounts for only a fraction of health outcomes; the conditions in which we live dictate the rest. We cannot expect NHS spending to resolve respiratory crises caused by the very architecture of our homes. Without a housing policy that explicitly targets health outcomes, rather than just assuming them, we risk undermining these vital NHS investments.

However, this investment focus reveals a clear imbalance. While £1.8bn is allocated to retrofitting, the broader determinants of respiratory health receive comparatively little attention. Targeted air quality improvements in deprived areas, employment support programs, and expanded primary care capacity have not seen equivalent investment. The policy prioritizes the measurable (upgraded buildings) over the complex task of lifting communities out of poverty. In doing so, it addresses thermal efficiency while leaving the underlying drivers of respiratory illness largely untouched.

The analysis reveals a mismatch between the stated goals of the retrofit program and the outcomes observed in the data. The policy was designed as a technical intervention, but it is being applied to a complex socio-economic problem.

The £1.8bn Warm Homes Plan was justified partly by projected respiratory health benefits, but the data from Greater Manchester suggests this justification does not hold in areas of concentrated poverty. While insulation remains vital for meeting Net Zero targets, the evidence does not support treating it as a standalone public health intervention in high-deprivation contexts. If reducing respiratory hospitalisations is a genuine policy goal, the data points toward different interventions: heating subsidies to address fuel poverty, employment programs to reduce financial stress, and improved healthcare access. We cannot simply insulate our way out of health inequality; without addressing the poverty that underpins it, the “health dividend” will remain a theoretical projection rather than a lived reality.

Top image by Muhammed Zahid Bulut.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole

Please feel free to use this post under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Full information is available here.