GDI Lecture Series: Development NGOs’ dependence on home government funding with Professor Lauchlan T. Munro

On Wednesday, 16 February, Professor Lauchlan T. Munro gave a lecture entitled ‘Too close for comfort, relatively speaking? Development NGOs’ dependence on home government funding in comparative perspective’ . You can listen to the lecture in full or watch the live stream below read more…

Climate change research based on Dhaka slum showcased at Rich Mix London

Dhaka is on the front lines of climate change, but what does that mean to the people living in its slums? Research into urban climate change resilience, led Dr Joanne Jordan to team up with the University of Dhaka to produce a Pot Gan, a form of interactive indigenous performance theatre, to encourage slum dwellers, researchers, practitioners and policy makers to reflect on the day to day realities of living with climate change in low-income settlements in Dhaka.

Dr. Joanne Jordan’s The Lived Experience of Climate Change project hit the road again recently to bring the stories from Dhaka slum dwellers to a standing room only crowd of 200 people at Rich Mix in east London.

True to the premise of the Pot Gan performances in Dhaka last year, the evening took on an interactive theme, with audience members actively engaging with the personal experiences of slum dwellers affected by climate change. read more…

GDI Lecture Series: Designing Interventions in Developing Water-Energy-Food Systems with Julien Harou

On Wednesday, 8 February, Professor Julien Harou, The University of Manchester gave a lecture entitled ‘Designing Interventions in Developing Water-Energy-Food Systems’. You can listen to the lecture in full or watch the live stream below read more…

Basic income beyond borders – a new mechanism for economic justice?

There’s been lots of discussion recently on the feasibility of introducing Universal Basic Incomes, so we were intrigued to hear that Laura Bannister and Sarah Methven, both Manchester alumni were running a conference to around the idea of doing this on a global, rather than national basis. Here’s their report back from the event last weekend:

Early afternoon last Saturday, the Deputy Mayor of Salford welcomed 130 people to the city’s oldest church for the sold-out first World Basic Income Conference.

The church sits among streets where centuries of boots have marched for workers’ rights, including the infamous ‘Battle of Bexley Square’, which inspired the best-selling novel and play Love on the Dole. This time people had gathered to discuss one of the world’s newest social justice demands. The conference was the first ever to examine proposals for a worldwide basic income, an idea which aims to fight extreme poverty and begin turning the tide on global inequality by directly redistributing money, proposed to begin at $10 per month for every adult and child worldwide. read more…

Free online courses on ‘Water Supply and Sanitation Policy in Developing Countries’

Our colleagues in the Alliance Manchester Business School have launched two Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs) on Water Supply and Sanitation Policy in Developing Countries, taught by Professor Dale Whittington and Dr Duncan Thomas. The courses will also feature Professor Diana Mitlin of the Global Development Institute.

Are these MOOCs free to take?

Both MOOCs will be free of charge for all learners who enroll. There are no prerequisites; both MOOCs are open for enrolment by everyone.

Global decisions and local realities: what drives sustainability standards, and who benefits?

By Aarti Krishnan and Dr Judith Krauss, PhD Researchers at the Global Development Institute

In an era when sustainability has become a buzzword, two key questions arise regarding sustainability standards in global production networks: what drivers underlie the adoption of sustainability standards, and what benefits do they entail for local producers? Looking at both Northern firms and Southern actors, we explore these questions through the cases of fresh fruit and vegetables in Kenya and cocoa in Nicaragua in a research project now published as a discussion paper by the United Nations Forum on Sustainability Standards.

Despite the countries being 8,500 miles apart and farming very different crops, we found considerable parallels between Kenya and Nicaragua: the cocoa and fruit and vegetable markets are primarily buyer-driven and Northern firms delineate what needs to be done to be ‘sustainable’, while grassroots actors (such as farmers) have lower agency and less space to negotiate the terms of sustainability. Different private-sector, public-sector and civil-society stakeholders hold different priorities: their commercial, socio-economic and environmental drivers were so varied as to be partly incommensurable. Lead firms’ push for traceability so as to safeguard food safety for consumers in the Global North took priority over communities’ interests in terms of safeguarding the long-term environmental viability of their cultivation and their socio-economic livelihoods. read more…

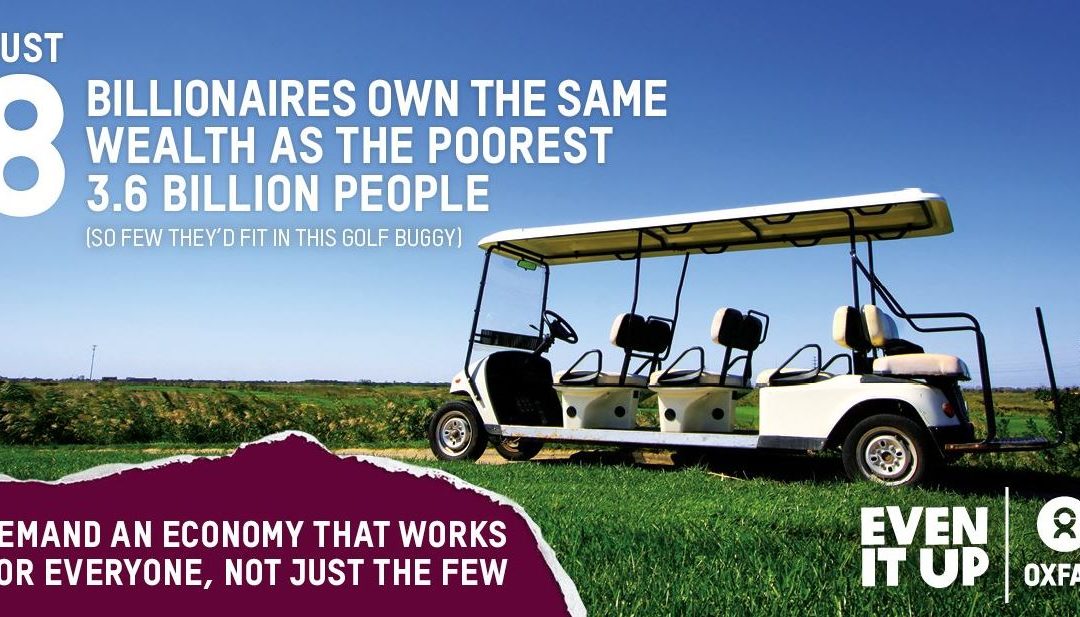

The inequality circus: another year, another set of misleading numbers

Following on from Rory Horner’s review of Oxfam’s recent report ‘An economy for the 99%‘, Tanja Müller presents a different view. This post was first published on Tanja’s blog.

No doubt, global inequalities are a serious issue, and they are getting worse in many ways (even if not exclusively so). And, Oxfam seems to have decided a long time ago, it always pays to put a sensationalist twist backed up by numbers on things. Of course Oxfam is not alone here in this area of so-called ‘post-truth’ politics. Remember the Brexit campaign slogan that suggested the UK would send £350m a week to Brussels – and that this sum could in future be invested into the NHS? It later turned out, the ‘Brexiteers’ knew very well this claim was wrong but found it a useful propaganda devise, as it ‘got people talking’, and in this case voting.

The same attempt to grab attention by whatever means seems true for the now yearly ritual of an Oxfam report released shortly before the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos. A couple of years ago, the report made headlines with the claim that 85 people owned as much as the poorest half of the world’s population, this then dropped to 80 and subsequently to 62 people in 2016. In the recent Oxfam report it dropped to eight people. Certainly a number that will get people talking, this new catchphrase that the world’s eight richest billionaires have as much wealth as the 3.6 billion people who make up the poorest.

For quite some time the way Oxfam comes up with its calculations – which are based on data from Forbes and the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report – have been heavily critiqued (some would say by people who have no interest in addressing the underlining problems of global inequalities, but I think that is a rather cheap shot). And indeed the numbers are quite controversial and often misleading, not least in terms of what is actually being measured and compared as wealth. Then there are those who point out that many of these super-rich in fact give vast percentages of their fortunes away to good causes. In doing so, they show civic responsibility and help make the world a better place in ways party politics can or does not do – while at the same time, one should say avoiding tax payments. I do not support this argument in any way as I have argued elsewhere, as it undermines democracy and any form of political accountability to recruit those who became rich through a system based on global exploitation and tax avoidance to fix the system. But does this justify the hyperbole in the way the state of global inequalities is being represented by Oxfam and the like?

Then there are those who think the controversy over data calculations does not really matter, as the important message is that inequality has reached highly unsustainable levels, and thus the yearly ritual of a new Oxfam catch-phrase headline is a welcome reminder of that state of affairs. Fair point in some ways, as argued thoughtfully by my colleague Rory Horner in a wider piece that reflects on a different economy.

But I beg to differ: language does matter, and so does hyperbole, and populism from the left or for a supposedly good cause is as destructive as populism form the right. It does destroy trust and the propensity to understand real-life problems based on facts, rather than on emotional appeals, and in doing so fosters the echo chamber of one’s own beliefs. In an interview an Oxfam spokesperson blames global inequalities for the rise in contemporary populism – but seems oblivious to the fact that the way its own message comes across is as populist and in many ways misleading.

Which begs the question, why does Oxfam continue to do this? One of its spokespeople told a German newspaper when queried about data calculations that the numbers in themselves did not matter, what was important was the scandal of inequality. But is there no other way to engage with that scandal and build a campaign around it than to use sensationalist numbers, however dodgy they may be? Of course there is, but that would be less flashy and not stick so easily, and ‘get people talking’ in the same way, presumably. Oxfam is, one should also say, by no means the only body who sees grave dangers in increasing global inequality – even publications like the Economist have issued warnings about it for some years now. Maybe, a cynic might suggest, it is the need to stand out in the crowd (and ensure its continued importance) that drives the annual Oxfam ritual? Slogans, in particular when based on imprecise facts, have hardly ever made the world a better, or indeed a more just place.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Staff Spotlight: Dr Tomas Frederiksen

Dr Tomas Frederiksen is a Lecturer in International Development at GDI and also one of our alumni. He is co-investigator on the ESID natural resources project, focusing on particular on the interactions between political settlements and corporate social responsibility at multiple scales in Ghana, Peru and Zambia.

What made you want to work in development originally?

I decided very early on that I was a global citizen, interested in problems globally, and very aware that I had certain life chances just by dint of where I was born. I didn’t think that was right, and I wanted to travel. So I did a degree based around looking at those problems, and went on from there.

I did my undergraduate degree in Development and Geography at Sussex University. I then worked in development in Denmark for a year and southeast Europe for four years, involved in youth policy and youth organisations. You can only get so far in an organisation without a postgraduate degree, so I came to The University of Manchester to do a Master’s in Poverty, Conflict and Reconstruction, followed by a PhD in Geography, and then did a postdoc at the University of Toronto for a year.

Call for papers: World on the Move: Migration, Societies and Change

30 October – 1 November 2017, Chancellors Conference Centre, Manchester

30 October – 1 November 2017, Chancellors Conference Centre, Manchester

The University of Manchester’s Migration Lab invites proposals for papers, workshops, exhibitions and performances which respond to the theme of ‘migration in the context of uncertainty and change’. For submission guidelines and information please visit the Migration Lab website.

Deadline for paper submissions: 30 April 2017

About the Conference

The conference will provide an arena for discussion, debate, and the development of future research projects. Plenary sessions from world-leading migration researchers, panels, and workshops will create spaces for the development of sustainable networks and relationships across the academic, policy, not-for-profit and media sectors. The first day will be a half day policy and politics event where distinguished speakers from policy, activist, NGO and media backgrounds will debate the question ‘How is Brexit Britain responding to a world on the move?’. read more…

From one President to another: David Hulme on Trump’s first week in office

David Hulme, Executive Director, Global Development Institute

This blog originally appeared in the Development Studies Association bulletin.

Starting the year with a moan (or perhaps a rant) did not feel like the sort of thing a ‘President’ (of DSA) should do. But now Donald Trump is my fellow-President (though his outfit is much bigger than our Association) and the social norms of what is expected of presidents are being contested. Do only ‘losers’ opt for courtesy, civility, transparency, respect, honesty, even-handedness…not sexually harassing people? I had hoped that his progressing from candidate to President-elect to President might change the rhetoric – what a sucker I am!

Listening to President Trump’s inauguration speech I was amazed to hear that the US is pretty much a failed state – it is a scene of ‘carnage’; an evil government has been denying its citizens access to basic health care; it is over-run by criminal immigrants; and, to protect itself it will need to do ‘what works’…torture foreigners. Populist national leaders, and Republican presidents in the US, seem to need a climate of fear to legitimate their ideas and themselves. But Trump has taken this to new peaks – life for the citizens of the US in 2017 sounds like a dystopian movie: take your pick – New York as Independence Day, Chicago as The Hunger Games, or Los Angeles as Divergent. Thank goodness we do not live there. It sounds like we should be sending survival packs to the US (but, that is no joke given how many homeless people I saw on the streets of Washington DC in December). Almost anything that is good in the US in the future will be due to Trump’s personal capacity to bring stability to this ravished land. (Forget that Obama provided Trump with a growing economy, national financial stability, rising employment and tens of millions of poor citizens with access to health care). read more…