Lose neither your hair nor your head: Six tips for starting the PhD journey

By Judith Krauss, post-doctoral associate at the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Doctoral College

How do you best combat the jitters of starting a PhD? With over a dozen new PhD researchers joining the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Doctoral College at the University of Manchester’s Global Development Institute, we called upon our existing PhD researchers to ease our new arrivals’ transition.

The formidable panel of Corinna Braun-Munzinger, Sally Cawood, Connie Kang, Lina Khraise, Virgi Sari, Ryo Seo-Zindy, Gaby Zapata Roman, Dani Malerba, Robbie Watt and Bala Yusuf kindly shared their much appreciated insights on the Do’s and Don’ts for the PhD journey.

Make sure you have a life to balance your work from the beginning. The PhD is a new step – unlike previous higher education, there are only a limited number of classes to attend, and most of the work will be self-directed. Consequently, it is easy to fall into unhealthy patterns of working long hours, which can become unproductive. As a result, taking breaks, distancing yourself from work, having friends who have no idea what a conceptual framework is (and frankly don’t care) is vital. But find your own path – you know best what can help you relax, and what can help you work more productively.

Whatever you do, share your thoughts and struggles – whatever you may be feeling, someone else will have felt it before you. Hopefully, that will help you avoid the fates of two of our PhD researchers: one lost all his hair in the first PhD year, and the other realised at one point that she had not talked to her husband for a week!

Data collection

Stay level-headed: it is absolutely normal if things do not go according to plan. As a result make sure you have enough flexibility to deal with inevitable delays, limited access to databases/interviewees, and take advantage of the unexpected opportunities which present themselves.

There is a fine line between making sure you answer your research questions, but also being responsive enough to seize unexpected opportunities. In all likelihood, you will have far more data than you need to write a PhD – the question then simply becomes: which PhD do you want to write?

There are likely to be opportunities to teach, support other research projects and reach out to the community through public engagement in the course of your PhD. Be selective. What you choose to take advantage of should also depend on what you aspire to do after the PhD, helping you develop skills extending beyond your PhD research (teaching, editing, publishing, conference organising, blogging, etc). Make sure your supervisors and other academics are aware of your preferences so they can let you know about suitable opportunities.

Working with supervisors

A PhD is not so different from project management– you have to realise that a PhD is your project, you are managing it, and you are calling upon the help of two trusted consultants (ie your supervisors) when you need their input.

There is a fundamental incongruence: whereas the PhD will be almost your sole focus, supervisors will have a myriad research, teaching, administrative, supervisory, etc, responsibilities. Make sure that you use your time with them well, go into meetings with a clear idea of what you need, and also respect their other responsibilities by not sending them a chapter to read one hour before your supervisory meeting. You need high-quality supervision for guidance, but ultimately, it is your PhD, and you have to write it: you cannot sit in your PhD defence and explain that you only did this because your supervisor told you to. This also means you may have to disagree with your supervisors occasionally. But remember, your supervisors want you to succeed!

Your PhD colleagues are your friends, in more ways than one. They can offer immediate help on things like literature to read or software to use, and most importantly, they will understand the ups and downs of a PhD better than anyone else. Make sure you reach out to PhD candidates outside of your own discipline as well. Everyone will struggle at some point –it is important to share those experiences, and to keep an eye on each other.

Finally, never compare yourself against others’ achievements. Each PhD journey is different.

The PhD experience

While the PhD journey can be trying, it is also important to appreciate it as a privilege: few have the opportunity to spend several years reading, writing and thinking about a topic they have chosen themselves.

Make sure you enjoy it!

A note on the new proposed welfare prediction method for Kenya’s cash transfer programmes

Dr Juan Villa, Honorary Research Fellow, Global Development Institute

During my PhD at the Global Development Institute, The University of Manchester my supervisor, Professor Armando Barrientos, would repeatedly say to me “Juan, you cannot end poverty without learning who the poor are.” Although simple and perhaps colloquial, this phrase summarises why targeting is an important element in the implementation of antipoverty programmes. Apart from measuring general figures on poverty, we truly want to know who those in poverty are to respond efficiently with antipoverty interventions in an environment of scarce resources.

The Government of Kenya is currently implementing four different cash transfer interventions targeted at individuals in poverty and grouped under the National Safety Net Programme (NSNP). The Hunger Safety Net Programme was introduced in four northern areas with support of the UK’s DFID; the Cash Transfer for Orphan and Vulnerable Children currently operates almost nationwide with the support of UNICEF; the Older Persons Cash Transfer and the Cash Transfer for People with Severe Disability (CT-PWSD) were created as national initiatives to protect households with different vulnerabilities. Although these interventions belong to the NSNP, currently they are implemented with independent targeting methods that try to predict household consumption expenditure. Coming back to what Professor Barrientos would say, these interventions intend to discover who the poor are but with different identification tools and four different views of poverty.

I worked alongside with the World Bank and the African Institute for Health and Development (AIHD) in Nairobi to develop a brand new targeting method that would replace those currently used by the four programmes. While it is common to find unreliable income or consumption expenditure information in developing countries, coming up with a new method would require the identification of individuals or households in poverty with a proxy of their welfare.

After reviewing several reports on current targeting practices, I noted that there was general dissatisfaction with the implementation of current methods. These methods were based on a prediction of an official measure of consumption expenditure that allows the construction of general poverty figures, with dramatic imputations of household auto-consumption (dominant in rural areas).

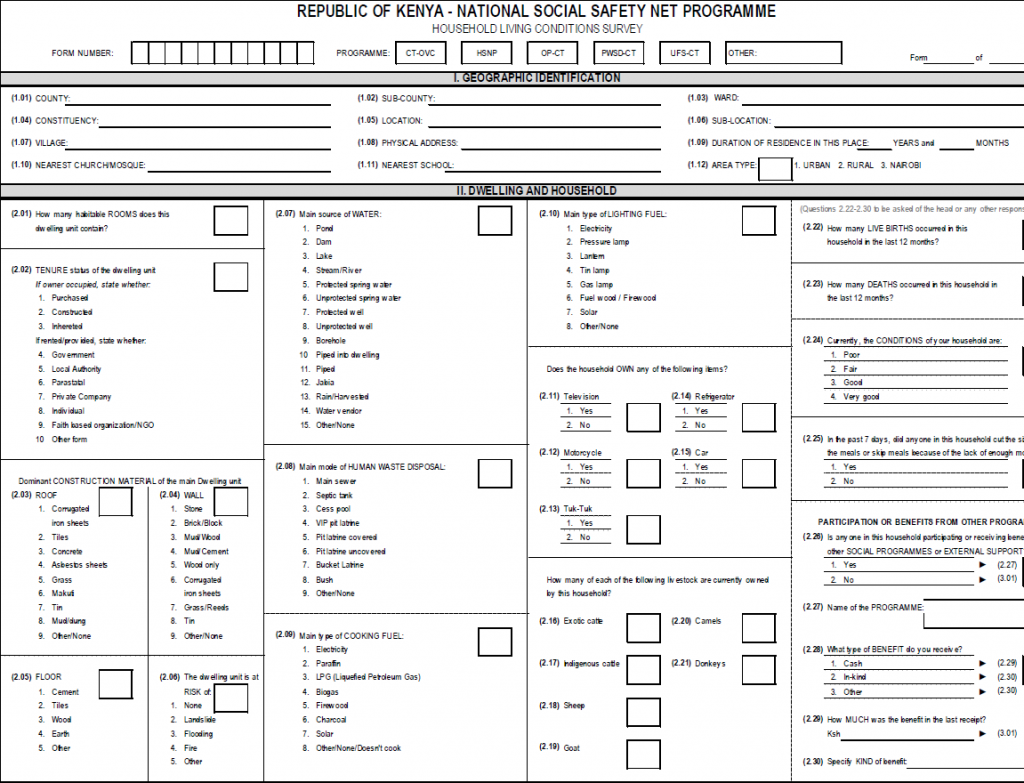

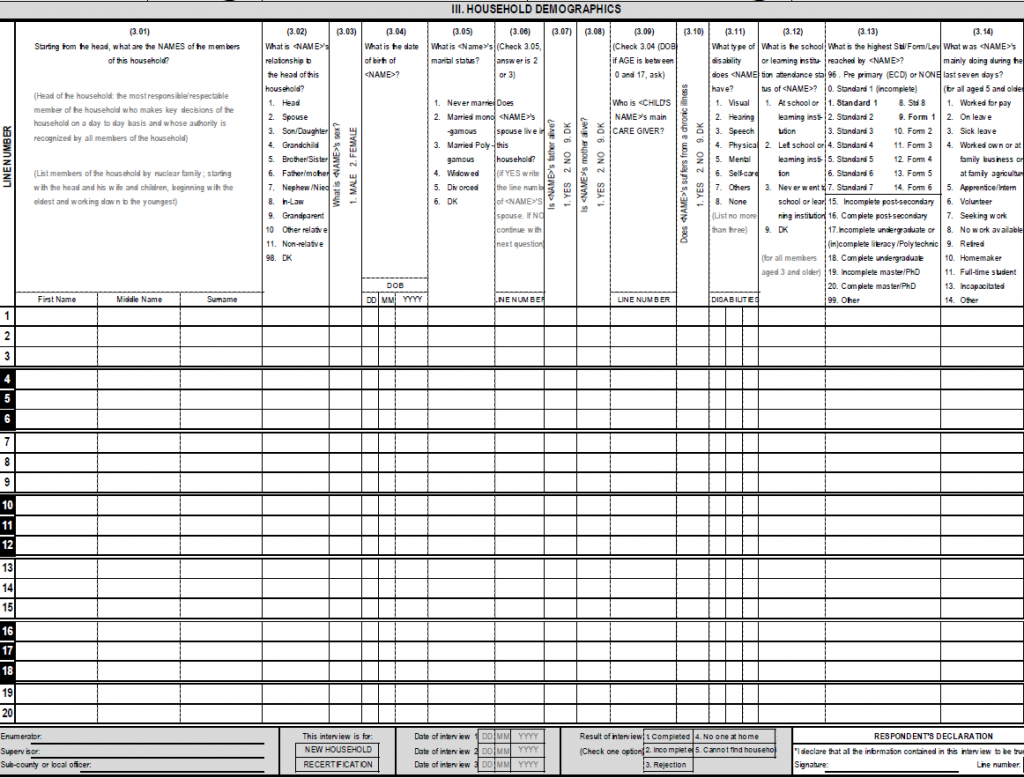

As we were more interested in targeting antipoverty transfers and not in measuring the national poverty headcount, I decided to apply different techniques that provide a proxy for household welfare bypassing the prediction of consumption expenditure. Based on the 2009 National Census data, I proposed a new questionnaire to collect the required information to generate a welfare score which is currently known as the Living Conditions Score (LCS). The LCS ranges between 0 and 100, with 0 being the household with the worst living conditions and 100 the household with the best in terms of dwelling materials, provision of electricity, water and sanitation, household composition and endowment of education attainment. The questionnaire is a two-sided form that can be filled out either manually on paper or with electronic devices:

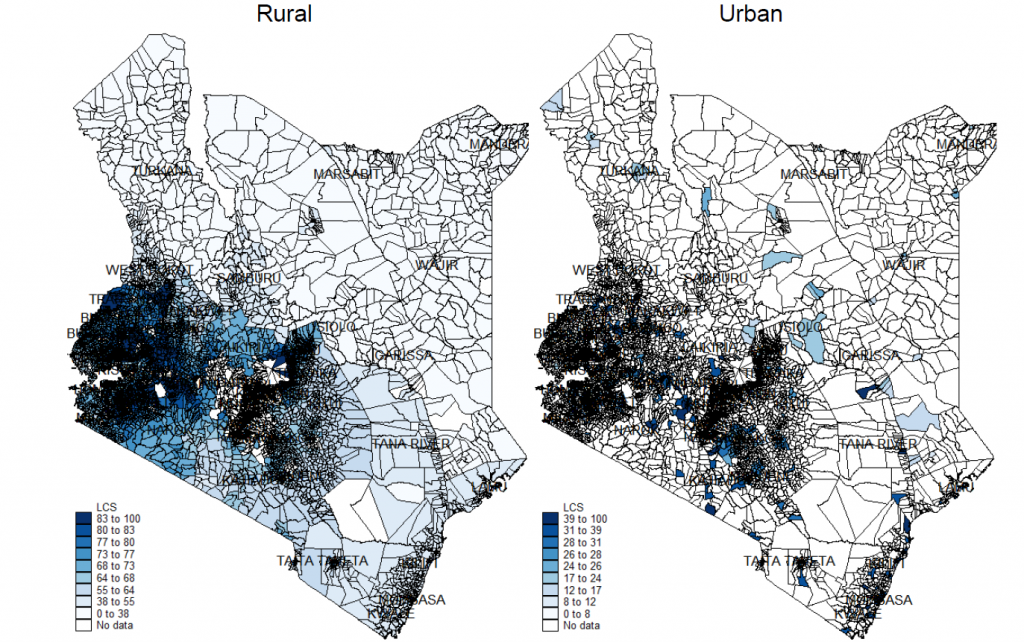

Given its censual nature, the resulting welfare score now allows the mapping of household welfare in Kenya in three geographic areas (Nairobi, rural and urban) with which the government can prioritise certain regions with acute poverty:

The technicalities of the LCS are shown in the paper cited below (or click here). The survey questionnaire and the LCS are being currently piloted by the Hunger Safety Net Programme with the support of AIHD in order to assess its reliability and adaptability with the community component of the targeting process at large. So far nearly 6,000 households have been surveyed with the new method and it is expected that by 2017 it can be adopted by the NSNP.

Several lessons emerged during the development of the new targeting tool for the NSNP. Firstly, the community component in the operation of the programme cannot be ignored. Communities are the most relevant actors in the implementation of the four cash transfer interventions of the NSNP and not allowing them participate in the targeting process with a reliable and objective proxy for household welfare might generate conflict and jeopardise the overall local operation of the interventions.

Secondly, the institutional arrangements are also important. The alignment of the four interventions to use the same poverty identification method was challenging at the beginning. Given the integration of the four cash transfer interventions into one single strategy, agencies and officials are prone to think that such merger could translate into the closing of some of them. After several clarifications the four interventions have agreed to unify their poverty identification methods.

- This blog is based on the working paper “A harmonised proxy means test for Kenya’s National Safety Net programme.”

Will the 2016 drought call time on southern Africa’s sugar fix?

By Professor Phil Woodhouse, Global Development Institute

Across southern Africa governments watch anxiously for signs that the forecast rains will arrive to break the 2015/16 drought that has devastated the region’s economy and left 40 million people, including 40% of the rural population in Malawi and Zimbabwe, facing food shortages that are set to peak next month. Even South Africa, normally a food exporter, is due to import 3.5 million tons of food in the coming months. The crisis throws into sharp relief the region’s need to drought-proof its agriculture, but also increases scrutiny on current investment into irrigation, which has been dominated by one crop: sugar cane.

The sugar industry in southern Africa has increased its output by two-thirds and the (irrigated) land it cultivates by almost 50% over the past 20 years. During this time, three South African companies have expanded their operations across the region where they now account for over 90% of sugar output. In a region where food production is vulnerable to drought, large-scale corporate control of land and water to produce a crop whose consumption is increasingly criticised on health grounds highlights the contradictory forces at work in contemporary African agriculture. An unprecedented collection of papers published this month by the Journal of Southern African Studies explores the dynamics of sugar cane production in seven countries in southern Africa and provides insight into the logic that drives the corporations, governments and local communities involved.

The sugar industry in southern Africa has increased its output by two-thirds and the (irrigated) land it cultivates by almost 50% over the past 20 years. During this time, three South African companies have expanded their operations across the region where they now account for over 90% of sugar output. In a region where food production is vulnerable to drought, large-scale corporate control of land and water to produce a crop whose consumption is increasingly criticised on health grounds highlights the contradictory forces at work in contemporary African agriculture. An unprecedented collection of papers published this month by the Journal of Southern African Studies explores the dynamics of sugar cane production in seven countries in southern Africa and provides insight into the logic that drives the corporations, governments and local communities involved.

While the collection bears out the specificity of different national contexts, some key factors stand out. First, the sugar industry offers to many African governments a tangible opportunity to develop modern agriculture and sophisticated industrial processing to deliver globally competitive products such as sugar and ethanol. Evidence from these studies questions the modernity and productivity credentials of sugar production in southern Africa, as elsewhere, not least in some of its labour practices. However, in pursuit of agricultural and industrial goals, governments make land and water available through special planning zones, protect their sugar markets from foreign imports and endeavour to build a constituency of support among rural communities through ‘outgrower’ schemes.

Second, the historical context is important. The rapid expansion of South Africa’s sugar companies across the region was possible by the liberation of South Africa’s businesses from the constraints of apartheid coupled with the budgetary pressure on neighbouring governments to divest themselves of loss-making sugar plantations. Yet such contexts change. The European Union market to which many southern African countries had privileged access has been reformed in the past decade and the South African sugar companies themselves are now the object of takeovers, including by European sugar refiners.

Against this shifting backdrop of international markets and corporate investment in agriculture, stability may seem a problematic concept. Yet, for southern African governments and rural land users perhaps the key trade-off has been between the stability and steady growth of demand for sugar and the volatility of markets for many alternative (food) crops. This year’s drought and the prospect of changing rainfall patterns associated with climate change suggest this trade-off may need further scrutiny. Sugar cane is a highly water-intensive crop requiring ten months or more of growth before harvest. Even if food is to be imported with cash earned from sugar exports, it is likely to be a very inefficient use of water if irrigation is to underpin the region’s food security. Yet, as these studies show, sugar production is a manifestation of many intersecting interests which reflect the historical and economic context of the different countries in southern Africa, as well as their contemporary political and economic dynamics. Efforts to bring about change must rest on an understanding of each local context.

Global Development Institute Lecture Series

The Global Development Institute Lecture Series brings together scholars involved in cutting edge research on international development. It aims to facilitate dialogue and discussion, providing a space for leading development thinkers to share their latest research ideas.

The Global Development Institute Lecture Series brings together scholars involved in cutting edge research on international development. It aims to facilitate dialogue and discussion, providing a space for leading development thinkers to share their latest research ideas.

The Lecture Series will begin on Wednesday, 12th October with GDI Executive Director David Hulme discussing his latest book ‘Should Rich Nations Help the Poor?’

Lectures will be held in Theatre B, Roscoe Building from 5.00 – 6.30pm BST.

- 12 October: Should Rich Nations Help the Poor? Professor David Hulme, Global Development Institute, The University of Manchester. Watch the lecture here.

- 26 October: The UK’s Post-Brexit Trade Policy: What about development? Professor Alan Winters, The Department for International Development, The University of Sussex. Watch the lecture here.

- 9 November: Capitalism and Conservation in the Age of Security: The Vitalization of the State Professor Elizabeth Lunstrum, York University. Watch the lecture here.

- 23 November: The Magic Number: 1.5°C or 2°C Limit on Warming. But, what does this actually mean for Least Developed Countries? Dr Saleemul Huq, Director of International Centre for Climate Change & Development and Senior Fellow at International Institute for Environment and Development. Watch the lecture here.

- 7 December: Bangladesh Confronts Climate Change: Keeping Our Heads Above Water Professor David Hulme, Dr Manoj Roy (Lancaster University) and Dr Joseph Hanlon (Open University). Watch the lecture here.

All the lectures will be followed by a Q&A.

The lectures will be livestreamed via Facebook Live. You can submit questions on Twitter using #GDILecture or in the Facebook Live comments section. The lectures will also be available as podcasts after the event. Find out more on the GDI website, Twitter or Facebook page.

Tracking the savings of poor households

Following on from David Hulme’s blog post Do you want to know how poor people really manage their money? Stuart Rutherford, an Honorary Research Fellow at the Global Development Institute, analyses the latest data from his fascinating financial diaries project.

The ongoing Hrishipara Daily Diary project collects data on the daily money flows of 50 low-income households living near a market town in central Bangladesh. Data collection started in May 2015 and we have published an ‘Interim Report’ covering some findings from the period up to the end of March 2016. In this blog we use more recent data to look at poor households’ savings patterns.

How poor are our ‘diarists’?

Using household net income as a measuring stick, we have categorized our 50 ‘diarists’ into four groups. The poorest have incomes which fall below the Bangladesh government’s ‘lower poverty line’ and we refer to them as extreme poor. Fifteen diarists (or about third of all diarists) are in this group. Another 7 diarists fall below the ‘upper poverty line’ and we call them very poor. Twelve more, our moderate poor diarists, have incomes up to double the upper poverty line and the remaining 16 enjoy higher incomes and we describe them as near poor. (The income figures include the value of produce farmed by diarists for their own consumption). The median income is 81 Bangladesh taka a day per person in the household, the Purchasing Power Parity equivalent of fractionally over US$2, not far from the World Bank’s ‘extreme poverty’ benchmark of $1.90.

Savings balances and savings flows

In the Interim Report we wrote about the savings and loan balances that our diarists hold in formal accounts at banks, insurance companies and MFIs (microfinance institutions like Grameen Bank, BRAC and ASA). What we found may surprise some readers. For example, we found that although MFIs were set up originally to lend to ‘the poorest of the poor’, in our sample the very poorest were the least likely to be using MFIs and in general the higher your income the more likely it was that you used MFIs. We also found that poor diarists who did use MFIs tended to use them more for saving than for borrowing. Overall, among all the diarists, savings balances were higher than loan balances. We concluded that it looked as if the MFIs have become the main receptacle for storing the savings deposits of a very large swathe of rural Bangladeshis, from the poor to the near-poor.

This analysis left many questions unanswered. Are diarists saving at other institutions besides banks and MFIs? What are their savings ‘habits’ – little-and-often or in occasional bursts, or seasonal? – and do these habits vary according to income level, or occupation, or some other characteristic? Who most likes to save? – we know that richer people tend to have bigger savings balances, but are they bigger relative to their income? And why do our diarists save?

Many of these questions are best researched by looking at the flows of income, expenditure, saving and borrowing, rather than looking at totals or balances. A strength of the financial diary methodology is that it reveals these flows in great detail and sets them in the context of the household’s economic, financial, social and even emotional life.

Going with the flow

To look more closely at savings flows, we take a sample of 44 of our diarists for whom we have complete transaction data for the six months from March to August 2016 (we have excluded six diarists for various reasons, such as their sending most of their earnings back to villages where we can’t tell how much of it was saved).

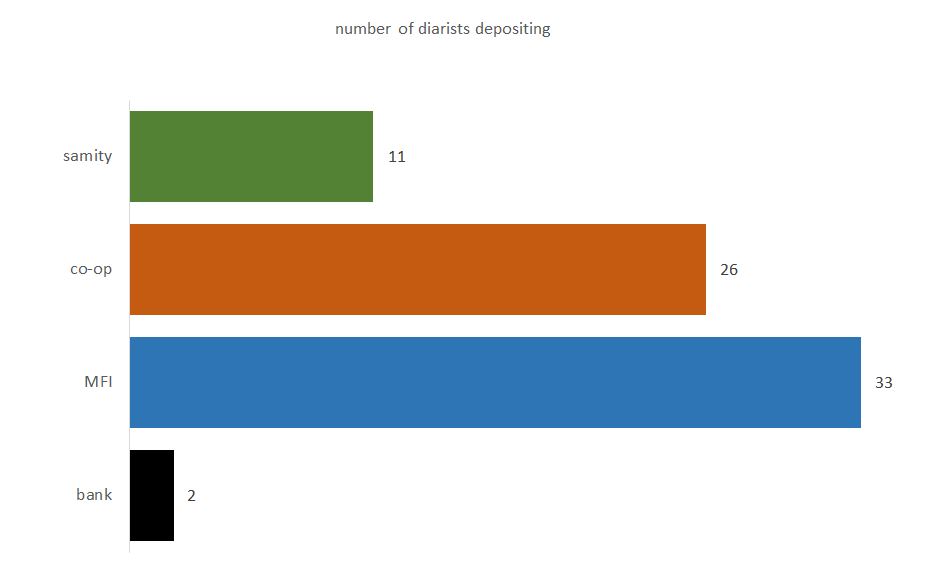

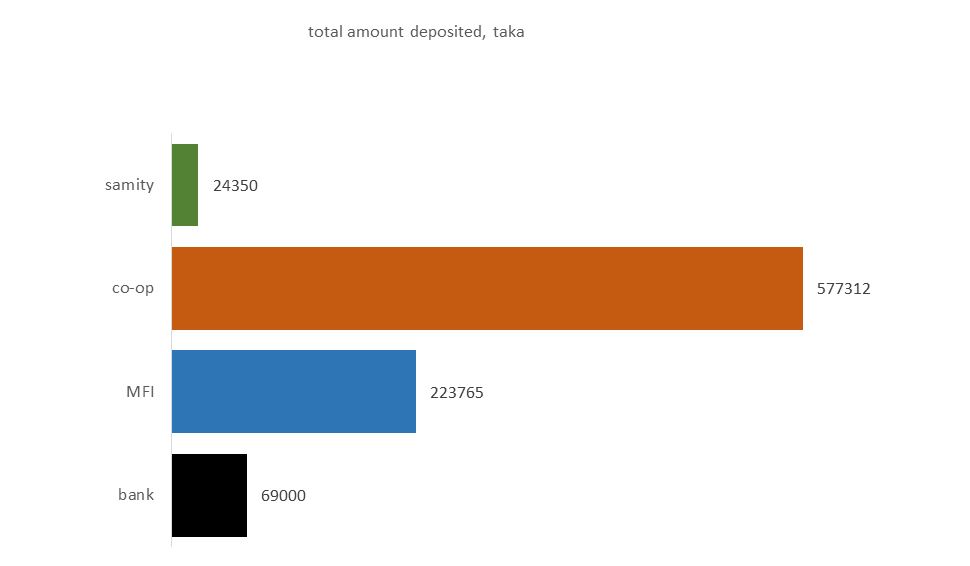

Records for these 44 diarists reveal two other popular places to deposit money besides formal banks and MFIs: the less formal local Co-operatives, and the informal village or occupational savings clubs, known in Bangladesh as ‘samities’. As the following graphics show, 40 of these 44 diarists deposited savings into one or more of these four options during the period. More diarists deposited into MFIs than in to any other destination, but the less formal Co-operatives came a close second, and the total amount deposited into these Co-operatives during the period was greater than any of the other options. Banks attracted only two depositors, and though a quarter of all diarists in the sample saved into informal samities, the amount they saved was small.

More diarists deposited into MFIs than in to any other destination, but the less formal Co-operatives came a close second, and the total amount deposited into these Co-operatives during the period was greater than any of the other options. Banks attracted only two depositors, and though a quarter of all diarists in the sample saved into informal samities, the amount they saved was small. Our diary records help to interpret these numbers. Generally speaking, the MFIs accept deposits only once a week, at a fixed time. The Co-operatives, on the other hand, take deposits at much more frequent intervals, and some send a collector each day to their clients’ homes or workplaces. Several of the samities take savings daily, but, being small entities based on the trust formed in a small community, they prefer not to handle large sums of money. All this suggests that being big enough to handle large sums, while at the same time nimble enough to collect deposits frequently, results in the most intensive saving.

Our diary records help to interpret these numbers. Generally speaking, the MFIs accept deposits only once a week, at a fixed time. The Co-operatives, on the other hand, take deposits at much more frequent intervals, and some send a collector each day to their clients’ homes or workplaces. Several of the samities take savings daily, but, being small entities based on the trust formed in a small community, they prefer not to handle large sums of money. All this suggests that being big enough to handle large sums, while at the same time nimble enough to collect deposits frequently, results in the most intensive saving.

Do savings rates vary with income?

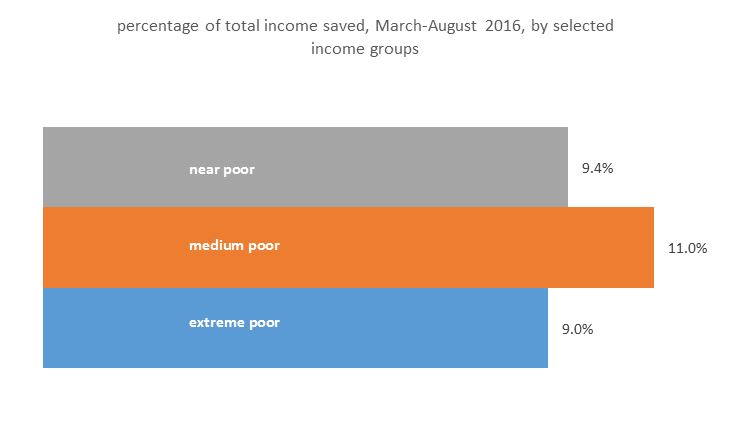

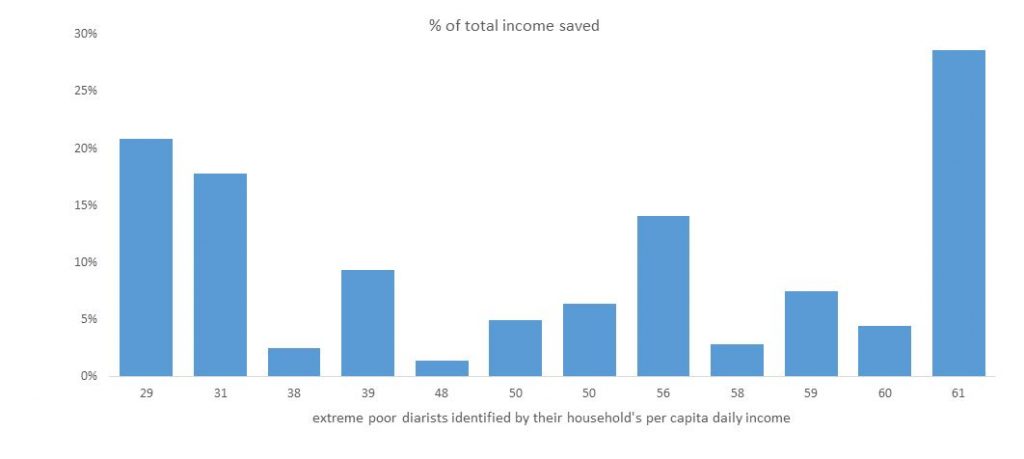

The next graphic shows the saving rates (the proportion of total income deposited into the four destinations noted above) for the six-month period 1 March to 31 August 2016, by selected income class (we have omitted the very poor class because the sample size is small).

What stands out is that our extreme poor diarists, despite their income poverty, save about the same proportion of their income as do the much better-off near poor.

Within these categories, though, the behaviour of individuals varies. Our last graphic shows the percentages of total income saved by the 12 extreme poor diarists in this sample. The poorest of all (on the extreme left of the graphic) is an illiterate widow who does odd jobs for market shopkeepers for a living and feeds herself and, for part of the time, her teenage daughter on an income of less than 75 cents (PPP) a day. By avoiding debt, by living extremely modestly, and by being determined, she manages to save 25 cents most days into a Co-operative and in that way saved one fifth of her total income during the period. Why does she do it? She tells us she isn’t saving for a particular expenditure, but to protect herself from illness, old age and misfortune, and to provide a better life for her daughter – including as a good a marriage as she can arrange for her. Such reasons for savings are the most commonly heard among our poorer diarists.

Why does she do it? She tells us she isn’t saving for a particular expenditure, but to protect herself from illness, old age and misfortune, and to provide a better life for her daughter – including as a good a marriage as she can arrange for her. Such reasons for savings are the most commonly heard among our poorer diarists.

These brief notes suggest that the propensity to save is common to all levels of poor households, but the rate of savings depends on a mix of factors: the savings opportunities that are available, the way in which savings is collected, and the specific circumstances and personality of the saver. Financial diaries are perhaps the best way to explore these issues in great detail.

Any reader who would like to grapple with the Hrishipara data can get them from the author at write.ser@gmail.com.

Sharing perspectives on labour standards and labour laws in rising powers

Many in Western countries think of emerging economies such as China and India as places with weak labour standards where workers are being exploited. This ignores changes on the ground in many ‘rising powers’ countries, such as China, India, South Africa and Brazil, which have seen systematic reforms in labour laws and codes as well as an emergence of voluntary corporate social responsibility (CSR) standards over the past decade.

A workshop held in Cambridge at 5-6 September 2016 brought together researchers from two projects under the ‘Rising Powers and Interdependent Futures’ programme with practitioners and experts to discuss these trends. Stimulating discussions over the two days not only drew on diverse perspectives across academic disciplines but also allowed policy-oriented exchange between academia and practice.

To investigate the complex changes in labour regulation and CSR in the rising powers, the two projects combine very different disciplinary and methodological approaches. From a law and economics perspective, researchers on the ‘Law Development and Finance’ project at the University of Cambridge explore trends in public labour regulation based on the Centre for Business Research (CBR) Labour Regulation Index, a unique quantitative dataset that documents labour laws in 117 countries over the period 1970 to 2013. The data first of all shows that labour regulation in rising powers is becoming increasingly strict. Another finding that may be surprising for some is that stronger regulation does not necessarily lead to losses in employment and productivity, but can improve economic performance.

Coinciding with these reforms in public regulation, the project on ‘Labour Standards and Global Production Networks’ at the University of Manchester finds an emergence of voluntary standards and local norms around CSR in China, India, South Africa and Brazil. Researchers from Manchester draw on qualitative methods and case study analysis to understand how these local CSR standards interact with state regulation and with global labour standards set by international organisations and Western multinational companies. Discussions during the workshop highlighted the very different understandings of CSR across rising power countries. They also underlined the need to take into account the different ways in which CSR interacts with public regulation in these countries.

Following from the lively exchange around labour reforms, academic researchers and practitioners arrived at the question: How can we bridge the gap between academia and practice better and more often? One key lesson was that closer academia-policy interaction could result in better ‘co-production’ of research, and in ways that might have greater impact. Discussions revealed, however, some challenges around the current debate on the wider impact of academic research. For instance, often practical impact is difficult to measure for a single researcher or piece of work, but becomes clearer for an entire body of literature that changes thinking and policy-making. Another challenge is that communication channels may not be conducive to academic research informing policy, e.g. if academic papers only draw conclusions for the literature, or if media interviews are cut too short to allow a researcher to communicate a differentiated idea. Some of the ideas for moving forward were to highlight policy conclusions also in academic journals and to foster links between media and academics that have become weaker over the past years.

For more details, please refer to the publications from the two projects:

- output from the Manchester project on the Rising Powers website

- output from the Cambridge project on the Rising Powers website and on the University of Cambridge website

This post first appeared on the Rising Powers blog

What matters most for improving the prospects of low-income and disadvantaged people?

We asked the participants of the DSA conference this question at the GDI stand last week, and gave them four options: politics, institutions, economic growth, or something else?

Although a blind vote might have made the results fairer, the winner is not particularly surprising considering that the conference theme was “Politics in Development”. Institutions had a brief surge on day two of the conference, but politics pulled ahead to win at the end. One of its supporters was GDI’s Executive Director David Hulme:

https://youtu.be/YVTuqVVlCDY

GDI’s PhD researcher Daniele Malerba chose economic growth, but differentiated his answer by low- and middle-income countries.

https://youtu.be/N8Po0ZE1KrY

The “Something Else” answer also had its fair share of support, led by Duncan Green who advocated for ‘social norms’:

https://youtu.be/b0PuYDUUeWc

All of these three factors (and many others) clearly matter, and most are intertwined with each other, but as a thought exercise, what matters most? What do you think?

GDI at #DSA2016 asked: what matters most for improving the prospects of low-income and disadvantaged people?

— Global Dev Institute (@GlobalDevInst) September 23, 2016

Reflections from the DSA: current issues, next goals and policy relevance in poverty research

Daniele Malerba, PhD Researcher, Global Development Institute

The 2016 DSA conference, themed around politics in development, involved an incredible number of interesting panels (and more than 600 delegates!). I was very pleased to present in the one focusing on “Poverty dynamics: shame, blame and responsibility”, which also had a strong focus on multidimensional poverty. The panel, running almost all day on Tuesday (chaired brilliantly by Keetie Roelen from IDS), was divided into three sessions, each covering a different sub-topic: discourse, measurement and social protection.

I was very pleased to present on this panel for many reasons. One of them is that the conference was held in Oxford, the hometown of the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI, developed by OPHI), giving a romantic element to the event – yes, researchers also have feelings… But more important was the relevance of the topics discussed. Rising inequality, especially in high-income countries, is increasing vulnerability to poverty. As the abstracts of the papers are available in the conference program I will not go into the details of the presentations but want to reflect on the main points discussed and what needs to be done next.

Current issues: definitions of poverty, long-term objectives and responsibility

Throughout all the presentations (and in other panels I attended) three extremely linked themes caught my attention as fundamental to the theme of the panel. The first is the definition and measurement of poverty. Do we conceptualize poverty as monetary or as multidimensional? If we consider the latter, what are the dimensions to include? This is not a new issue. But it is of increasing importance now with the widespread use of direct antipoverty policies in developing countries. Some of them (such as conditional cash transfers, CCT, or integrated poverty reduction programmes like the Chile Solidario) focus on the accumulation of human and physical capital. These programs align closer to the multidimensional definition of poverty and have a longer term vision. On the other hand, unconditional cash transfers address poverty more as a lack of income. It is clear that the conceptualisation of poverty drives policies.

This distinction is a preamble for the second point of interest. Decreasing long term (vulnerability to and) poverty does not imply just temporarily filling temporary income gaps alone. There has to also be a focus on transformational and productive aspects which can create benefits and payoffs also in the long run. Examples include increased education, which brings higher labour market outcomes and earnings, or investment in agricultural machinery which leads to higher output – both typically seen as components of CCT or integrated programmes. This does not mean that unconditional cash transfers cannot achieve these goals as well: for example, higher lump sum transfers are associated with more physical capital accumulation. Any poverty alleviating policy should take these long term goals into account. It is worth noting that some of these transformative dimensions (such as learning quality) are difficult to measure or the data is not available. This is the main reason for their exclusion from indicators such as the MPI.

Thirdly, the responsibility cannot be given to a single person or a single actor. If transformative effects of antipoverty policies need to be achieved, all agents need to play a role. If a CCT programme has the effect of increasing school enrolment, but the school infrastructure is poor and the teachers are absent or of poor quality, how can children improve their education? The objective of CCTs and other human development antipoverty policies is human capital accumulation so final outcomes (learning, health status) should be the ones that matter the most, compared to intermediate goals (school enrolment or visits to health clinics). Responsibilities should be then shared among the agents responsible for the supply-side services (such as infrastructure) as well as the recipients.

https://youtu.be/N8Po0ZE1KrY

What comes next: better data, social and geographical poverty traps, and the need for complementary interventions in antipoverty policies

Given these core issues, what can and should be done? Firstly, improve data quality and its collection frequency, to improve poverty estimations and to include additional relevant dimensions (such as test scores or individual learning outcomes).

Secondly, the goals of antipoverty programs need to take into account the geographical and social poverty traps where many poor people are located. This is important not just because the normalisation of poverty is a big danger for many social groups and geographical areas, but also because the concentration of the poorest in disadvantaged clusters entails more structural policies to address vulnerability and poverty. This is important for development as a whole, as we see that the majority of the global poor now live in specific pockets in middle income countries – and not in low income countries. And despite growth and available resources at the national level, they still remain poor and are excluded from the development process.

Finally, antipoverty programs, especially the ones looking to have a transformational effect through, for example, investments in human capital, need to be complemented by supply side programs through coherent policy architecture, such as ensuring that school enrolment is complemented by good quality teaching. A positive example from Brazil comes from “Brasil Sem Miseria”, a programme launched in 2011 which takes a holistic approach to poverty eradication. This programme complements pre-existing direct antipoverty transfers (such as the well-known CCT Bolsa Família) with other policies related to the supply of good infrastructure or labour force policies.

Reflecting on these last two points in particular, I was wondering if we need to push for a second wave of impact evaluations for many social policies. Most of these policies are implemented at a national level and what we usually know is the overall impact, when information and analysis of the local mechanisms might be more insightful.

In fact, an average positive effect of a program could also be the result of high positive impacts in some areas and low, or even negative, ones in other locations. And it is of fundamental policy relevance to understand what drives these different impacts. Following the last Nobel price winner in economics Angus Deaton, should we not move beyond average effects of these policies and look at deeper and important causal mechanisms?

The problem with inequality in developing countries

By Caroline Boyd, Addressing Global Inequalities #ResearchBeacons Campaign Manager

Inequality and climate change: Two new and pressing challenges to global development which, together, form a heady mix for researchers, governments and NGOs striving to address global inequalities.

Professor David Hulme’s recently launched book, ‘Should Rich Nations Help the Poor?” prominently features these two issues. The challenges around the inequality element in particular are further reinforced in a recent Policy Brief by Professor Stephan Klasen – a research collaborator of the Global Development Institute and the University of Manchester’s Chronic Poverty Research Centre with particular expertise in gender, chronic poverty and poverty measurement.

What do we know about the rising inequality in developing countries?

Since the 1980s the rising inequality within developing countries has been a key factor in the increase in social and political instability, making it no surprise that reducing inequality became a new goal within the Sustainable Development Goals.

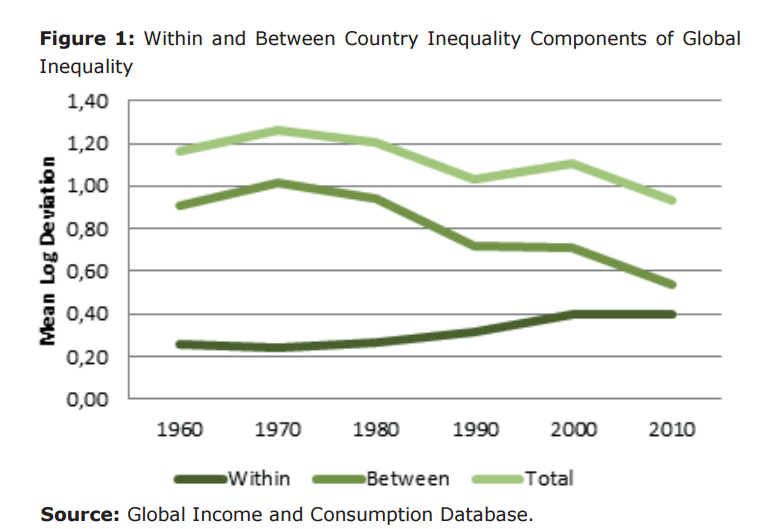

Stephan Klasen comments that within-country inequality is responsible for the sharply rising share of all global inequality. Through the decomposable inequality measure (seen below) an underlying trend shows that between-country inequality has been falling since the 1970s whilst since 2000 the marked improvement in higher growth rates in many poor African countries also contributed to falling inequality overall. In contrast, in-country inequality has been rising substantially since 1980 and – if estimates for the top 1% were also included – the rise in overall inequality would be even faster.

So what does this mean for the world?

In harmony with the views of Professor Hulme’s book, Stephan Klasen clearly states in his latest policy brief that one of the biggest changes of recent times in terms of inequality is that we now live in a world where it matters nearly as much for your economic fortune if you are born rich or poor within a country as it matters whether you are born in a rich or poor country. This is a situation which means we should rightly be concerned about the rise of within-country inequality and the huge impact this type of inequality is having on lives and on the wider global inequality picture.

“We now live in a world where it matters nearly as much for your economic fortune if you are born rich or poor within a country as it matters whether you are born in a rich or poor country”

– Stephan Klasen

And this is where policymakers come in. These new inequality trends are not related to unchangeable economic forces. They depend to a great extent on the policy choices by governments. This means there is scope and opportunity for more a pro-active inequality reducing agenda. One which Stephan Klasen argues should be developed and led by the countries in question and one which, as David Hulme argues, other richer countries can and should support.

- Read Stephan Klasen’s full PEGNet Policy Brief titled “What to do about rising inequality in developing countries?”

- David Hulme’s book, “Should Rich Nations Help the Poor?”

- Addressing global inequalities – one of our five #ResearchBeacons of excellence

“Mobile Technology for Agricultural and Rural Development in the Global South” Workshop, 20th October, The University of Manchester

The “Mobile Technology for Agricultural and Rural Development in the Global South” Workshop, will be held on 20th October 2016 at The University of Manchester. An initiative of the Centre for Development Informatics (CDI) at the Global Development Institute (GDI), University of Manchester, UK in collaboration with CABI (Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International).

The aim of the 20th October 2016 Workshop is to share research and practice on current trends in “mobile technology for agricultural and rural development in the Global South”: specifically to bring together researchers from diverse disciplines and practitioners with experience of implementing mobile applications and agriculture information systems in differing country contexts. We hope the workshop will shape a future research agenda and form the basis for future research and practitioner partnerships, as well as contributing to an edited book publication.

Read the preliminary list of speakers. If you have any questions please contact: richard.duncombe@manchester.ac.uk