GDI at the Development Studies Association Conference

The Global Development Institute is helping to convene seven panels at the annual DSA conference in September. The focus of the conference is politics in development.

For full details of each session and to proposed a paper, click on the title.

Power, politics and digital development [Information, Technology and Development Study Group]

Convenors: Richard Heeks (University of Manchester), Mark Graham (University of Oxford), Ben Ramalingam (Institute of Development Studies)

The panel will cover the broad intersection of power, politics and digital development including both directionalities – the impact of power and politics on design, diffusion, implementation and outcomes of ICT application; and the impact of ICT application on power and politics – and their mutual interaction.

Challenging media representations of refugees and exploring new forms of solidarity

Convenors: Tanja Müller (University of Manchester), Uma Kothari (University of Manchester)

This panel explores the diverse representations of the current movement of refugees into Europe. Through an examination of the politics of representations the panel explores the extent to which representations have the potential to create spaces of resistance and forge new forms of solidarity.

The politics of public sector transformations

Convenor: Pablo Yanguas (University of Manchester)

The public sector remains an inescapable component of development. Moving beyond the limited agenda of public sector reform, this interdisciplinary panel addresses public sector transformation as a contentious and transnational process of organisational and political change.

China and the rising powers as development actors: looking across, looking back, looking forward [Rising Powers Study Group]

Convenors: Khalid Nadvi (University of Manchester), Alex Shankland (Institute of Development Studies), Jennifer Hsu (University of Alberta)

The emergence of China and fellow ‘rising powers’, such as Brazil, India, South Africa and Russia, is having a profound impact on international development. This panel examines the multiple interrelated ways in which rising powers are (re-)shaping international development trajectories.

The politics of the migration-development nexus: re-centring South to South migrations [Migration, Development and Social Change Study Group]

Convenors: Tanja Bastia (University of Manchester), Kavita Datta (Queen Mary)

This panel aims to re-frame the migration-development nexus from the perspectives of regional South-South migrations and interrogate the potential for a more expansive migration-development nexus which extends beyond financial and economic priorities to consider wider political concerns.

Global production networks and the politics and policies of development

Convenors: Rory Horner (University of Manchester), Matthew Alford (University of Manchester), Fabiola Mieres (Durham University)

Global value chains and production networks constitute the backbone of global trade and are subject to attention by both policymakers and political contestation. This 2 session panel explores the economic, social and environmental challenges of GPNs and their developmental policy ramifications.

Beyond the ‘new’ new institutionalism: debating the real comparative politics of development

Convenors, Kunal Sen (University of Manchester), Sam Hickey (University of Manchester)

The panel addresses how politics shapes economic/social development through a focus on the findings of the Effective States and Inclusive Development research centre. The presentation of the findings will be followed by a discussion of their implications for rethinking the politics of development.

Would increased migration reduce global inequality?

By Daniele Malerba

Inequality is a topic of major interest nowadays, with recent reports showing that the richest 62 individuals possess more wealth than the bottom half of the global population. But this attention has not always been there.

One the main drivers of this new “inequality movement” has been the recent recession, coupled with the stagnant incomes of the middle classes. But Branko Milanovic, one of the pioneers of this movement, discussed also the importance of data improvements in the recent trend of inequality analysis.

During a masterclass with PhD students at the Global Development Institute, he argued that the increased availability of household level data has been impressive. This is especially true for Africa where the coverage rate increased by more than 20% in the last 20 years. Current advancements in the availability of data also includes: fiscal information to complement household surveys, the use of top incomes in inequality estimates (as they are not represented in common household surveys) and information on inequality of wealth. Improvements in the amount of information available is also helping to develop new fields of inquiry, such as the concept of inequality of opportunities as opposed to inequality of outcomes, the decomposition of inequality and growth, and historical inequalities.

Moreover, the increased coverage of data and the effects of globalisation, has enabled the study of global inequality, the inequality between all individuals in the world, regardless of country. In his public lecture, Milanovic, who has been assembling data from different countries in order to build a global income distribution, explained his findings and the policy implication for some of today’s main issues, such as migration and the future of the middle class.

Inequality between and within countries

To better understand global inequality, it is important to separate it conceptually it into inequality within nations and inequality between nations.

Inequality within countries, measured by the national Gini coefficients, increased in most nations between 1988 and 2008. The increase was mainly driven by market inequality (wages and returns from financial assets), which was cushioned by the use of redistributive capacity to make final disposable income less unequal.

More interestingly Milanovic pointed out that the majority of countries experiencing increasing inequality, such as the US, might be on a second Kuznets curve. On the other hand countries like Brazil (and many other LACs) and China are still moving along the first Kuznets curve. Their experience of decreasing inequality is the result of increased spending on social transfers, reduction of the education premium and minimum wages.

Inequalities between nations, which is usually conceptualized as looking at differences between country’s mean incomes, has decreased in the past 20 yearsmainly due to growth in Asian countries. Despite this, some facts remain striking. The figure below shows, for example, that not only is the mean income in Denmark’s remarkably higher when compared to a group of African countries; but there is also no overlap between the income distributions. This means that the poorest group in Denmark is richer than the richest group in Uganda (excluding billionaires which are not represented in household surveys). Similar patterns can be found comparing many rich and poor countries.

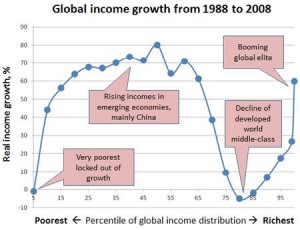

Finally, what if we look then at global inequality as a whole? First of all 1988-2008 was the biggest reshuffling on incomes since the industrial revolution. Decline in global inequality was accompanied by four main features: the large gains captured by the top 1% of the global distribution, the growth of the Asian middle-class, the “zero-growth” of the middle class of many western states such as the US, and the stagnant incomes of the bottom of the global distributions. The second and third points brought the emergence of what Milanovic calls the “global middle class” who earn between $10 and $100 US dollars a day. The size of the rising Asian middle class also meant that the global median income has been rising at a faster rate than the global mean income.

Secondly, the major driver of inequality is still location (between countries), meaning the country where you are born largely determines your income. As shown previously using the example of Denmark and African countries, the poorest group in one country might be richer than the richest group in another country. This is a change from 1850, when inequality was more prevalent between class (within country inequality) and location, representing Marx’s “world of classes”. The projections for the future, with the rise of Asia suggest the continuation of the current trend of diminishing importance of the location component, which might translate into further reduced global inequality (as well as structural change of the inequality decomposition).

The implications for migration

Milanovic outlined a number of policy implications that could reduce global inequality. The first possible solution is to increase growth in poor countries (and their mean incomes). The second tool is migration.

When people migrate from poor to rich countries their income increases. Given the importance of the location as a determinant of inequality, the gains are potentially large. In addition to this, the costs associated with travelling are reducing, meaning that labour supply is increasingly being globalized – in a way that hasn’t happened previously.

Does this mean advocating for growth in the rate of migration from poor to rich countries? Milanovic proposes trade-offs between migration and citizenship rights; this means allowing intermediate cases of partial citizenship, in order to mitigate migration flows. Regardless of the specifics, his proposals suggest one important thing: we need to get serious about global inequality and its consequences.

You can listen to Branko Milanovic’s lecture ‘Globalization, migration and the future of the middle classes‘ in full here:

Watch | Uma Kothari ‘Is water safer than the land? Public perceptions of Syrian refugees and the power of a warm welcome’

Professor Uma Kothari’s lecture was part of ‘Your Manchester Insights’.

Listen | Branko Milanovic on globalisation and the middle classes

Professor Branko Milaonvic spoke at the Global Development Institute on ‘Globalization, migration and the future of the middle classes’.

Branko is a leading scholar on income inequality. He is Presidential fellow at City University of New York, Visiting Presidential Professor and Senior Scholar in the Luxembourg Income Studies Center. He previously served as Lead Economist in the World Bank’s research department. He is the author of The Haves and the Have-Nots: A Brief and Idiosyncratic History of Global Inequality, as well as numerous articles on methodology and empirics of global income distribution and effects of globalization.

Call for Abstracts: “Big and Open Data for International Development” workshop

Big and Open Data for International Development workshop

Tuesday 12 July 2016, Centre for Development Informatics, University of Manchester, UK

This is a call for abstracts/presentations on big and open data for international development, with an initial deadline of 30 April 2016.

In recent years, there has been growing activity around the “data revolution” in international development including formation of the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data. As ever-more and ever-faster data is available about trends, patterns and processes, then related decision/action systems will be significantly affected. Growth in research in this field has been slower and much remains to be done, particularly in bringing a socio-technical perspective to the creation, processing and use of new forms of data in development.

The aim of this workshop is to share socio-technical, socio-organisational and critical research on “data revolution” trends: most notably big data and open data. We hope the workshop will shape a future research agenda and form the basis for future research partnerships.

The following timeline will be observed:

- 30 April 2016 – prospective presenters to submit an abstract of 200-400 words outlining their proposed presentation to: cdi@manchester.ac.uk

- 8 May 2016 – presenters to be notified of response to abstract

- 8 July 2016 – draft papers (desirable but not essential) to be circulated to workshop participants

- 12 July 2016 – workshop in Manchester for presentation and discussion of papers

If you have any queries prior to abstract submission, do please ask.

Anita Greenhill, Richard Heeks, Jaco Renken, Pedro Sampaio

Centre for Development Informatics, University of Manchester, UK

We acknowledge funding support for this workshop from the Alliance Manchester Business School and Global Development Institute of the University of Manchester

Uganda field trip by GDI students

Some of our Master’s students are currently on fieldwork in Uganda. This video, of the March 2015 trip, gives an insight into their visit.

Last year three of our students also wrote blogs about the fieldwork they carried out. You can read them now.

Listen | Tomas Frederiksen on corporate social responsibility in the mining sector

Dr Tomas Frederiksen spoke last week as part of the Global Development Seminar Series. Tomas discussed whether corporate social responsibility in the mining sector can deliver development.

Listen to the talk:

The Global Development Seminar Series brings together scholars involved in cutting edge research on international development. It aims to facilitate dialogue and discussion, providing a space for leading development thinkers to share their latest research ideas

Find out more about the other seminars in the Global Development Seminar Series.

Do global value chains lead to forced labour?

Malaysia is a country which has experienced tremendous economic growth from the 1970s onwards, moving to upper-middle income status in the mid-1990s (Felipe 2012). One of the key industrial sectors that led its transition out of an agrarian society to an industrial one was the electronics industry. Malaysia was one of the first developing countries that inserted itself into the vast global value chain of the electronics industry.

Malaysia was one of the earliest locations where multinational corporations established offshored factories in the country’s free trade zones in the early 1970s. This led to a creation of a set of domestic firms, which specialised as suppliers of parts and components to a large number of multinational corporations in the country. While there was significant growth and some upgrading during the 1980s, the industry and importantly domestic firms have experienced stagnation since the late 1990s. The electronics industry in Malaysia has been unable to upgrade further and move up the global value chain (in value added terms) for many years (Rasiah et al 2015). Critically, it faces competition with new production locations such as Viet Nam and India.

A major reason behind the failure of the electronics industry in Malaysia to grow further is its deep embeddedness in the global value chain. Malaysia entered the electronics industry global value chain with very little domestic capability of its own. Rather, the industry was created with an excessive openness to foreign investment and multinational corporations. Multinational corporations did not only bring production to Malaysia, they also brought with them a set of interests, which were taken up by the Malaysian government as policies, to maintain the industry as low cost and labour intensive.

One of these policies has been the maintenance of low wages in the industry. As the Malaysian economy grew and wages rose during the 1990s, domestic workers were no longer interested in the low paid factory jobs offered by multinational corporations in the electronics industry. The solution to this problem, which was backed by large multinational corporations with large factories in the country, was an influx of low paid foreign workers. Today, foreign workers are a significant feature of the electronics industry in Malaysia. While there are no exact numbers, there are estimates that up to 60% of the workforce in large factories are foreign workers (personal interview 2015). The majority of these workers hold temporary contracts and are hired by labour agencies, which are poorly regulated and whose networks are not transparent (Simpson 2013).

The demand for low paid workers, has also, tragically, led to a high incidence of forced labour (Verite 2014). In its damning report, which was commissioned and funded by the United States Department of Labor, Verite (2014) found that a third of the 501 workers it interviewed were in a situation of forced labour. This report raises serious questions about how an upper middle-income country which hosts major electronics firms with global reputations, such as Intel, Hewlett-Packard, AMD, and Motorola (note: the report does not name which firms were found to have forced labour), has found itself in a situation of forced labour amongst its foreign workers. It also raises questions of how global value chains are implicated in the incidence of forced labour.

For Malaysia, there are various factors at play. An excessive openness to foreign investment has led to the inability of domestic firms to upgrade in the electronics industry. The large and significant presence of multinational corporations has essentially led to a crowding out of domestic innovation and capabilities. More significantly, multinational corporations in Malaysia are interested in maintaining the production location as low cost and labour intensive as possible (Raj-Reichert 2016). While this would normally contradict with characteristics of an upper middle-income country, Malaysia has, however, artificially maintained low wages with the influx of foreign workers (Malaysia is reported to have the largest number of foreign workers in South-East Asia (The World Bank 2013)). This is being done through a network of labour agencies that are poorly regulated, largely non-transparent, and which have historical roots of informal worker recruitment dating back to the 1970s (Chin 2002).

The combination of a fast paced order and delivery schedule of the electronics industry global value chain and government policies, that have failed in innovative upgrading and that have resorted to maintaining a large multinational corporation dominated low cost labour intensive industry, are significant factors which have led to forced labour in the electronics industry in Malaysia.

References:

Chin, CBN (2002) The ‘host’ state and the ‘guest’ worker in Malaysia: Public management and migrant labour in times of economic prosperity and crisis, Asia Pacific Business Review, 8 (4), 19-40.

Felipe, J (2012) Tracking the Middle-Income Trap: What is it, who is it, and why? Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series.

Raj-Reichert (2016) ‘How global value chains contribute to the middle-income trap: a case study of the electronics industry in Malaysia’, Presentation at ‘The Political Economy of the Middle-Income Trap: Towards “Usable” Theories in Development Research” 24 February 2016, King’s College London.

Rasiah, R, Crinis, V, and Lee, H-A (2015) Industrialization and labour in Malaysia, Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy¸ 20 (1) 77-99.

Simpson, C. (2013) ‘An iPhone tester caught in Apple’s supply chain’, Bloomberg News. http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/2013-11-07/an-iphone-tester-caught-in-apples-supply-chain#p1 (accessed 9 September 2015).

Verité (2014) ‘Forced labor in the production of electronic goods in Malaysia: A comprehensive study of scope and characteristics’. Amherst: Verité.

World Bank (2013) Migration and remittance flows: Recent trends and outlook, 2013−2016, Migration and Development Brief 21, Migration and Remittances Team, Development Prospects Group (Washington DC).

Gale Raj-Reichert is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the Global Development Institute.

Corruption and its role in development

The use of public office for private gain benefits a powerful few while imposing costs on large swathes of society. Transparency International publishes an annual Corruption Perceptions Index which measures the perceived levels of public-sector graft by aggregating independent surveys from across the globe.

OECD countries appear less in the top 25 which is largely formed mainly of failed states, poor African countries and nations that either were once communist or are still run along similar lines. Comparing the corruption index with the UN’s Human Development Index (a measure combining health, wealth and education), demonstrates an interesting connection. When the corruption index is between approximately 2.0 and 4.0 there appears to be little relationship with the human development index, but as it rises beyond 4.0 a stronger connection can be seen whereby corruption at this level impacts negatively on development. As development experts, we should be interested in this dynamic.

The work done by the Effective States and Inclusive Development research centre investigates what political contexts are needed for development to succeed. Transparency International looks specifically at sectors where we should be shining a light to ensure transparency of action, objective and lack of corruption and that progress or action doesn’t work against development goals.

Corruption in Defence and Security is Dangerous, Wasteful and Divisive:

- Public trust: Corruption erodes the public’s trust in the armed forces and, in some cases, can undermine trust in the government as a whole.

- Government integrity: The government exists to serve its people, and defence and security establishments to protect them. When defence and security establishments are corrupt, the integrity of the government is undermined as leaders abuse the power entrusted in them for personal enrichment.

- Economic impact: Corruption is costly and a waste of a country’s scarce resources as defence and security are expensive areas of a national budget, even when conducted with integrity.

- Threat to security: Corruption is a danger to security and anti-terrorism policies, even contributing to regional and international instability.

- Peace keeping: A critical element in the conflict resolution and/or immediate post-conflict phase is the role of the military and a compromised defence force impacts a country’s ability to restore peace.

The need for transparency in the pharmaceutical industry:

- Provision of services: Corruption weakens the quality of services and in some cases can deny access to healthcare

- Economic impact: Corruption in the sector has a corrosive impact on health, negatively impacting public health budgets, the price of health services and medicines, and the quality of care dispensed.

- Knowledge is power: There is a knowledge gap between the providers and users of healthcare, leaving patients subject to the knowledge they are provided by healthcare providers, suppliers, and regulators. This inequity of information is open to exploitation for private gain, opening possibilities of corruption.

- Temptation: The volume of funds involved in the sector provides incentive for private gain. Due to the high number of people involved in decision making, and the often bureaucratic nature of the pharmaceutical and health sectors, it is susceptible to individual discretion and regulatory capture.

Find out more about Transparency International’s work in defence and the pharmaceutical industry and listen to the full lecture here:

Britain in the EU and the importance for development

Last week, I added my name to letter calling for the UK to remain in the EU. You can read the letter, signed by leading development experts, in The Guardian newspaper.

I, and my peers signing the letter, believe that for UK development agencies, the EU membership is essential to tackling global problems.

We know that the UK is global leader in development and leaving Europe would set us back as well as diminish our ability to influence European responses to development. Being part of Europe is a practical way to extend our influence and tackle global problems and so EU membership is vital to the UK’s ability to tackle global challenges, specifically cooperation within the EU will be essential to tackling the humanitarian emergency in Syria, the migration crisis, and the wider issues of peace, security and development in the Middle East and north Africa.

Simon Maxwell, the former director of the Overseas Development Institute who helped to organise the letter, said: “The signatories to this letter represent the UK’s global leadership in international development. As practitioners and advocates in international development, our strongly held view is that the EU needs UK heft and engagement to achieve its global goals – and that the UK multiplies its impact when it works with and through the European Union.

“We now urge the huge numbers of people who support development work in the UK, locally and nationally, to give the EU’s role in international development the profile it needs as we campaign to remain in the EU.”