Spotlight: Diana Mitlin, managing director of the Global Development Institute

What’s the current focus of your research?

My research focuses on the priorities of low income households in urban areas, looking at what’s happening and how things can be improved. I’m pretty obsessive about maintaining this focus so it doesn’t really change.

In terms of urban development, I don’t really look at what a city development strategy might look like from the perspective of the local government or businesses. It’s much more about how low income households and communities navigate development processes and power. In practical terms I tend to look at issues of tenancy, housing and the provision of basic services such as water and sanitation.

What research projects are you most proud of being involved with?

It’s a difficult question as I think most knowledge moves around getting tested out by other academics and professions. I think is really hard to attribute any specific changes to anything I have written. It’s only when you look back at it later that the broader impacts tend to be more visible.

Having said that, there was a paper I wrote in 2008 on co-production in development. This was then used by Shack/Slum Dwellers International, a network I work closely with, to help re-conceptualise the work and approach they were taking.

I’ve also done work around the upgrading of informal settlements and the approaches that social movements have used to advance grassroots development. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation subsequently came in with almost US$30 million of funding, to support the approaches and initiatives I’d been writing about and involved with.

What excites you most about the Global Development Institute?

The teaching and research that’s done within the Institute is both significant and influential. I think that we can shape the way that academics think through how development can best contribute towards a world that is more prosperous and just.

The Global Development Institute has been set up with a very clear direction – to addresses global inequalities in order to promote a socially-just world in which all people, including future generations, are able to enjoy a decent life. Collectively, we have a real opportunity to think through how to realise that ambition and make a positive contribution.

Within the Institute, we recognise that the world is rapidly changing. The barriers and differences between the Global North and Global South are breaking down. We need to understand how a bunch of academics sitting in Manchester can add value to development processes. This will involve more collaboration with existing communities, researchers and knowledge generators that we work around the world and will require additional collaborations to be established. It will be a hugely intellectually stimulating, but challenging task.

What are the main challenges facing the development sector at present?

To be frank – what’s not a challenge? It’s abundantly clear that our macroeconomic models are struggling to respond to the tests they are facing in the Global North, before you get anyway near applying them to the Global South. We don’t have a good grasp on how you maintain growth, let alone how to make it equitable.

The environmental challenges we’re facing are enormous. Do we have the right tools to achieve the ambitious targets the world has set itself? How do we adapt and mitigate against the effects of climate change in a way that’s pro poor?

There are a plethora of development programmes and interventions, many of which simply don’t work. Some programmes end up institutionalising disadvantage rather than addressing it. There’s a huge job to make sure that government and agency projects respond and align to the existing priorities of the people they’re trying to help.

What’s the one thing you always pack for fieldwork?

A pair of running shoes. On the last fieldwork trip I did with GDI students in Uganda, we even managed to form an impromptu running club, roping in some of our Ugandan hosts!

Imagining Solidarity Conference

On 19-20 May the GDI will be hosting a conference on ‘Imagining Solidarity: Visual representations of development in public campaigns’.

The aim of this conference is to explore the realm of the visual to examine how the complex relations of embodied, material encounter and engagement between people and visual campaigns shape discourses of development and forms of solidarity. It will seek to develop new theoretical insights into public and popular representations of development and forms of solidarity, to provide empirically grounded analysis of how ideas about solidarity are being imagined visually in public campaigns and charity adverts and to contribute to public debate and policy making on the use and impact of popular images.

The aim of this conference is to explore the realm of the visual to examine how the complex relations of embodied, material encounter and engagement between people and visual campaigns shape discourses of development and forms of solidarity. It will seek to develop new theoretical insights into public and popular representations of development and forms of solidarity, to provide empirically grounded analysis of how ideas about solidarity are being imagined visually in public campaigns and charity adverts and to contribute to public debate and policy making on the use and impact of popular images.

More specifically, the conference will address the economic, political and socio-cultural dimensions and implications of visual images promoting solidarities through addressing the following questions:

- What do visual images reveal about the production of emergent meanings and values around difference, otherness and inequality, that underpin ideas of development, through their depictions of people and places?

- How do visual representations combine economic imperatives with ethical responsibilities for development by evoking a visual language of care, interdependence and a common humanity?

- In what ways do public campaigns aimed at creating global solidarities suffuse everyday space and shape western public’s ethical disposition towards people overseas and foster the emergence of moral communities across distance and over time?

- What are the historical antecedents of representations of other people and places and how do they shape ideas and images of contemporary visual campaigns?

- How do different audiences respond to visual representations of solidarity and with what material, political and economic effects?

- What are the connections between these representations and development goals and outcomes?

Conference conveners:

- Uma Kothari (Global Development Institute, University of Manchester)

- Dan Brockington (Sheffield Institute for International Development, University of Sheffield)

The conference provides an opportunity to bring together academic researchers from various disciplines as well as producers of images and the organisations that use them to promote their causes.

It is free to attend but places are limited so please email uma.kothari@manchester.ac.uk and debra.whitehead@manchester.ac.uk if you are interested in participating.

Ramblings of an inquisitive traveller with a magicians hat: the PhD fieldwork experience

By Aarti Krishnan, PhD researcher, Global Development Institute

As clouds scudded across a beautiful crimson sky, I remember sensing a knot in the pit of my stomach. To be honest, it was the anticipation of going to an unknown country, but I do, however, recall blaming it on aeroplane food. It was my first time visiting Kenya and as the aeroplane finally landed, I remember feeling unprepared for what lay ahead despite, all the fieldwork preparation I had done, the journal articles and reports on horticulture farmers I spent months reading and the ideas I came with on it might be. Especially because Kenya was only known to me through reading published articles and what I saw on TV!

Isn’t that how many of us start out with fieldwork? Brimming with notions of what we believe could possibly be true. This partial certainty (it is short-lived as many PhD researchers will attest to) that our ideas may actually have some critical mass, comes from the fact that we gather extensive knowledge during our first reading year, albeit through secondary sources at the start.

I have always found it hard to place myself as a researcher on the development studies spectrum, like many others I too am multi-disciplinary. My work speaks to economists as well as economic and environmental geographers and therefore, I have been labelled by qualitative researchers as being a positivist and by economists as being a critical realist. Both research paradigms are tough realms to conquer! So I did what I thought was best and wore the only hat that I was sure of, the ‘practical one’, a passive critical realist that comes from meticulously scourging the internet for everything I could find on horticulture production networks in Kenya and formulating an educated hypothesis of the underlying drivers. Armed with that knowledge I began the process of extrapolating what I thought might help answer my research questions.

PhD Fieldwork #101- the blackhole effect: Stress and time pressures are something you sign on for when you begin a PhD. I came to Kenya looking for solutions to what I thought were complex, yet well structured questions. However, the more I learned, the less I knew. Halfway through my six months of fieldwork I ended up with a whole bunch of new and more convoluted questions than I had come with! It felt like I was floating in a blackhole with no sight of light!

PhD fieldwork #102- the sponge effect: I feel like I am always behind, and that I need to talk to ‘every stakeholder’ that is relevant however distantly to my research to get a holistic picture of what might really be happening. I did this by plunging into fieldwork, and like a sponge soaked up as much information and knowledge as possible, with hopes of wringing out the answers to my research questions.

PhD fieldwork #102- the sponge effect: I feel like I am always behind, and that I need to talk to ‘every stakeholder’ that is relevant however distantly to my research to get a holistic picture of what might really be happening. I did this by plunging into fieldwork, and like a sponge soaked up as much information and knowledge as possible, with hopes of wringing out the answers to my research questions.

PhD fieldwork #103- the Oceans 11 effect: Different researchers plan differently, some plan each day meticulously, with a detailed excel sheet, stylized fonts and highlights for different stakeholders and locations. While other researchers may want to take a more fluid approach and go with the flow. I began optimistically with the former, but ended up doing a bit of both. Planning in advance is all well and good, however the world does not dance to your schedule! I came to this realization after being stood up twice for the same interview in a matter of days. My advice – stay flexible, if you plan like in Oceans 11 … and it works, then you are definitely in a movie!

After interviewing a considerable number of stakeholders, I reached – what I think can be called a tipping point…where I had to make a choice about how I felt about my research and how actively I wanted to be part of it. Either I could decide to keep my practical passive hat on and continue to ‘listen’ but not really ‘hear’ what I was being told. Or I could allow the heartfelt discussions with the wonderful people I interviewed to really sink in and manifest itself in my work with a researcher-activist hat on. This mean meant actively seeking ways to create tangible positive outcomes for them. Both hats are very dynamic, but have their own pros and cons.

I was able to talk to over 600 fruit and vegetable farmers from central Kenya, who told me their stories not only through my rather impersonal questionnaires, but through their actions. Every farmer I visited, shared the little they had with me, be it some of their precious export quality fruits, their humble and delicious lunch and tea at times. How could I not feel privileged?

After such moving interviews, I spent a few minutes looking at the last farmer I interviewed on day 125, unsure of whether I would be able to only wear my passive researcher hat anymore. On one hand, I wanted to finish my PhD on time, while on the other I also wanted to help the people I met in whatever small way I could. I just was not sure of the best way to do that. It is common knowledge that most PhD students are eternally broke!

After such moving interviews, I spent a few minutes looking at the last farmer I interviewed on day 125, unsure of whether I would be able to only wear my passive researcher hat anymore. On one hand, I wanted to finish my PhD on time, while on the other I also wanted to help the people I met in whatever small way I could. I just was not sure of the best way to do that. It is common knowledge that most PhD students are eternally broke!

I had spent almost six months absorbing stories of struggle and survival melded with stories of hope. At the end of fieldwork, I remember sitting amidst a beautiful mangrove, contemplating how I should feel at the very end…happy that I got the answers I came for? Sad that it is over? Content with what I had understood? Or more confused about what was really ‘real’? Should I have some greater more profound feelings that people feel at the end of difficult and stressful journeys? But I don’t remember feeling any of it. Instead I left Kenya feeling a bit anxious, still pondering how I could juggle my hats in a way that did justice to both my research and to the amazing people that I had encountered.

It took me a while after coming back from fieldwork to realize what Kenya had given me. It was an opportunity to tell two stories. One that was full of practical wisdom, the one that I knew is what a PhD thesis is meant for… while the other one that woke the activist in me, who wanted to make a difference no matter how small.

It was only after this roller coaster of an experience did I realize that a PhD is not just a piece of intelligent well researched work- that is meant to sit on shelf somewhere; it is like a piece of art that needs to be shared. The PhD fieldwork experience not only brought out the practical researcher in me but the activist one too- enabling me to take the middle ground and pen down their story wearing both my hats.

It was only after this roller coaster of an experience did I realize that a PhD is not just a piece of intelligent well researched work- that is meant to sit on shelf somewhere; it is like a piece of art that needs to be shared. The PhD fieldwork experience not only brought out the practical researcher in me but the activist one too- enabling me to take the middle ground and pen down their story wearing both my hats.

PhD Fieldwork #104- The dust storm effect: my fieldwork went by like a storm, starting slowly, with highs and lows, then speeding up and before I knew it I was back in the UK, seated on my familiar desk with a cup of coffee. That being said, fieldwork turned many stones. It motivated me in ways I didn’t know were possible… it offered me the promise that both my hats together would not only be enough for a PhD, but also lit up a path that might last me a lifetime. I went to Kenya with a single hat, and came back with at least two and a rabbit in both and who knows how many more hats are in store. So I guess I just want to remind fellow researchers out there to never underestimate the magic PhD fieldwork can bring!

Listen | Judith Heyer on Rural Labour Hierarchies

Judith Hayer, The University of Oxford, spoke as part of the Global Development Seminar Series. Her lecture examines data from a long-term study of villages north west of Tiruppur to compare manual and low-skilled employment options open to people who do not have Higher Education of any kind.

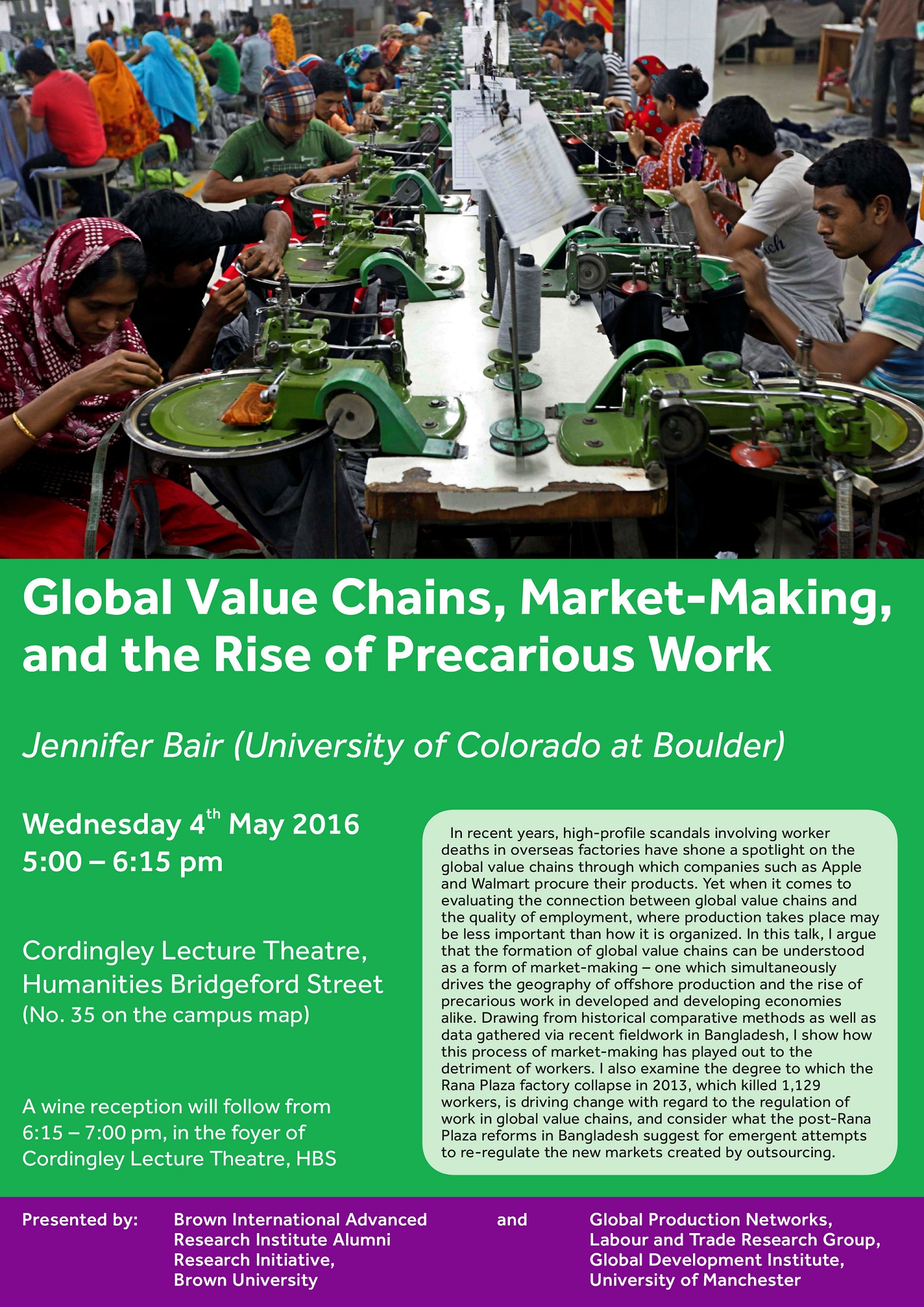

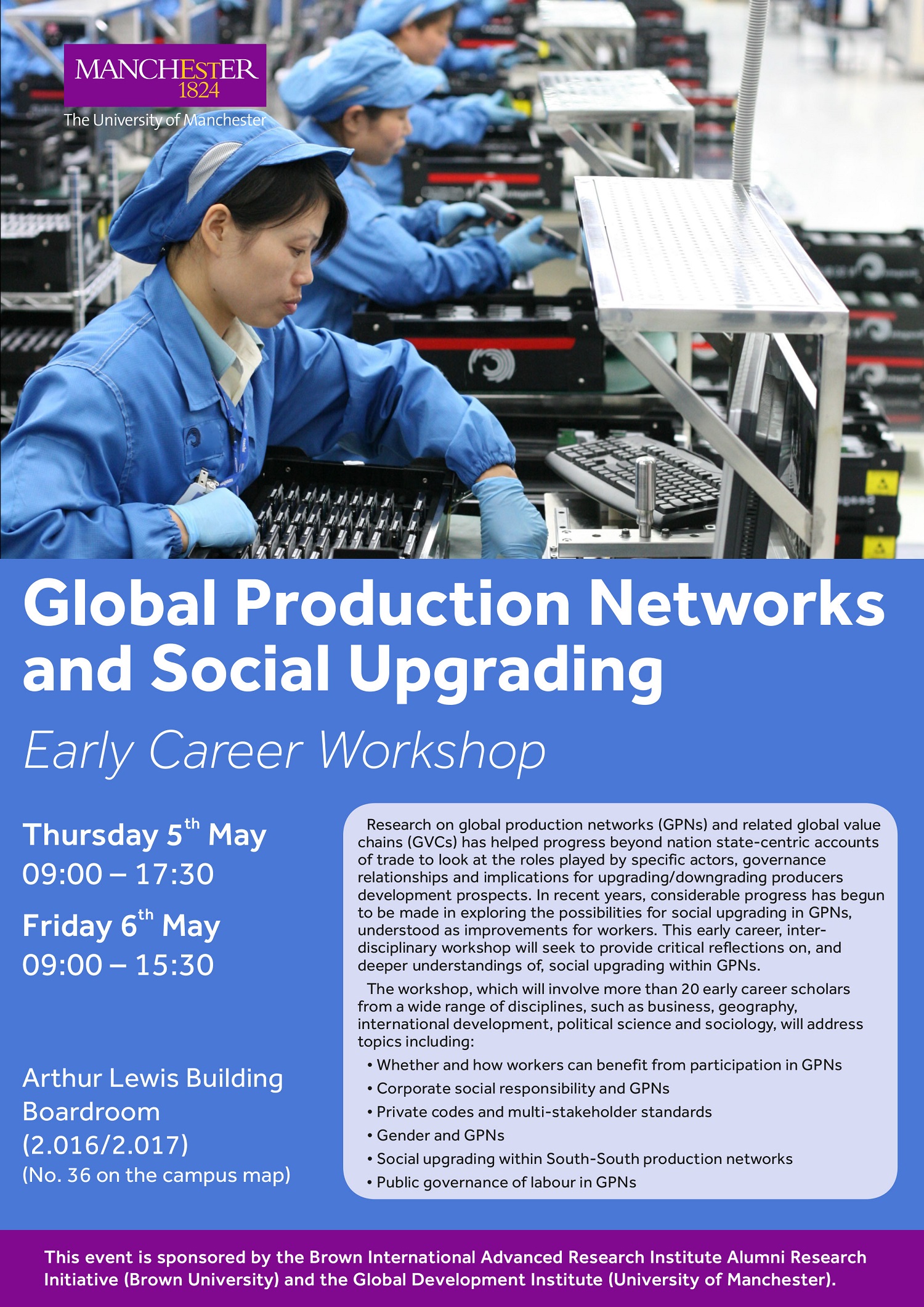

Workshop on ‘Global production networks and social upgrading’ 4 – 6 May

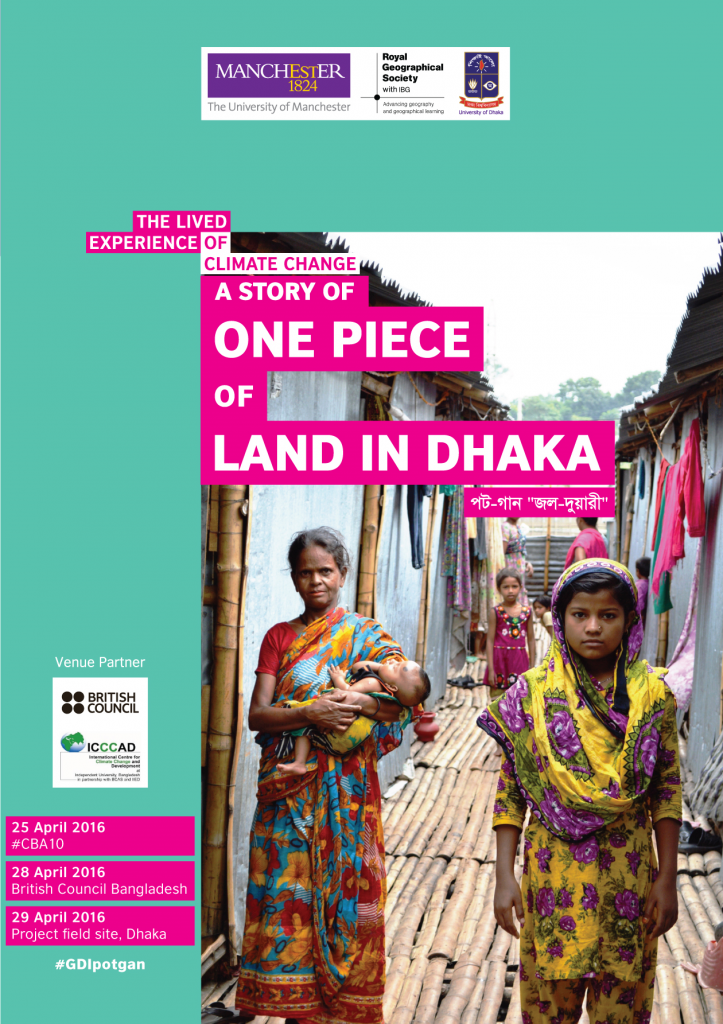

Innovative new research reveals the lived experience of climate change in Dhaka through a Pot Gan Performance of ‘Jol-duari’

Climate change intensifies the exclusion suffered by the poorest, but what needs to be done to support the people of Bangladesh to respond to one of the biggest environmental and development challenges of the 21st century?

Dr Joanne Jordan from the GDI spent months in the slums of Dhaka talking to 646 people in their homes, work places, local teashops and on street corners to understand how climate change is linked to many other problems experienced in their ‘everyday’ life.

Joanne’s study set out to understand how land tenure influences climate change impacts and in turn how land tenure can influence strategies for enhancing climate resilience in a Dhaka slum. The research found that some adaptation strategies that could enhance the urban poor’s resilience to climate change are limited by land tenure arrangements. Limited access to resources and assets can trap the urban poor in locations that have a high vulnerability to floods.

One slum dweller explains their limited ability to access land with low flood risk: “The water came up to my waist, our houses drown? Where can we go? The more water, the less the rent. The rent is low here. The owner is going to raise the land, but the rent will go up. This will not help me. We will move somewhere else. We are poor, wherever we can get cheap rent, we move there.”

With the research completed, Joanne teamed up with the Department of Theatre and Performance Studies, University of Dhaka to explore the findings through a ‘Pot Gan’; a traditional folk medium, featuring melody, drama, pictures and dancing. This project aims to create a new and modernised form of Pot Gan moving towards a documentary drama. Performances will be used to build awareness of how climate change affects the lives of those living in Dhaka slums.

Dr Joanne Jordan said “Communicating the research findings is important for building awareness and action on climate change. The live performance of the Pot Gan allows me to present my research in an entertaining way that encourages audiences to actively engage with the research material. Most importantly, it gives an insight into the lives of the urban poor who experience climate change by highlighting their personal experiences.”

The collaboration between Dr Jordan and the University of Dhaka has resulted in the Pot Gan being developed as part of a Master’s course unit on ‘Theatre for Development’. The director of the Pot Gan, Mr Ahasan Khan said “Theatre for Development is important for our students to learn about crucial global issues, such as climate change and to utilise traditional modes of indigenous theatre, such as Pot Gan, to foster a new dimension for story-telling. But, in order to revitalise the practice within modern society, we asked ourselves: what will be the form of Pot Gan in the 21st century? We used projections and digital print photographs instead of the traditional practice of hand-drawing the backdrop canvasses for the show. We are excited to present this experimental work.”

Performances of The Lived Experience of Climate Change: The Story of One Piece of Land will take place:

- 25th April 2016 at 6:30pm. The 10th International Conference on Community-based Adaptation to Climate Change.

- 28th April 2016 at 7:00pm. British Council Bangladesh, Dhaka.

- 29th April 2016. Within the community that provided the insights for the research.

These performances will form part of a documentary to be screened to both international and national audiences.

You can follow updates on twitter using the hashtag #GDIpotgan

Project Funders

This project was financially supported by the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) with an Environment and Sustainability Research Grant, The University of Manchester Humanities Strategic Investment Research Fund and the School of Environment, Education and Development Research and Impact Stimulation Fund.

Listen | Nicola Banks on youth poverty in Arusha, Tanzania

The Global Development Institute’s Dr Nicola Banks spoke about her latest research into youth poverty in Arusha, Tanzania. The lecture looks at what the experience of urban poverty means for young people and their social and economic development, highlighting the need to look beyond these narrow indicators to understand what it means to be young and poor in a city context.

You can also read Nicola’s blog post: Tackling Youth Unemployment in Arusha: From Knowledge to Action.

What are the ESID findings on Ghana?

So the Effective States and Inclusive Development (ESID) team are back in Manchester following a great week in Ghana. It was a hot and steamy 30 degrees in the vibrant city of Accra and during a brief power cut we realised how thankful we were for the AC! Debate and discussion on the politics of development in Ghana was heated and Ghanaians were particularly engaged in the pressing issues affecting their lives and livelihoods. These included public sector reform, structural transformation, natural resources, education and health.

Working with our fantastic hard working partners, CDD, we held an intense few days of events at GIMPA, UGBS, The World Bank and ISSER. We also attended a packed schedule of appearances on Ghana’s TV and radio and at one point we were right across Ghana’s airwaves. Discussion and debate continued into the evening and some of us are now vowing to stick to lettuce after consuming copious amounts of the heavyweight specialities banku and fufu.

The week was also a vital opportunity to get feedback on our research. We based our presentations and discussions on four briefing papers and from discussions and questions were able to consolidate our findings. These can be divided into four key areas:

- Competitive clientelism has undermined the long-term vision and capacities required for structural transformation in Ghana, including short-termism, electoral imperatives, and patronage. The problem is not competition itself, but that in Ghana everything is up for competition. Systemic changes may be required, for example going past the winner-takes-all model. However, our focus is on how democracy can be safer for development in Ghana. Our research shows how you can navigate the political space that you have. There’s a need to take advantage of the democratic dividend that is civil society, the media space, etc., the commitment to being rule-bound around elections.

- There needs to be a balance between top-down capacity and bottom-up accountability. Neither is robust enough to work without the other in the context of Ghana’s competitive clientelist political settlement.

- Our evidence on ‘what works’ suggests that there is a strong case for approaching the promotion of state capacity in Ghana with a more realistic agenda of supporting ‘pockets of effectiveness’ in a range of key areas. There needs to be coordination and coherence in the full sector to get the best out of these pockets of effectiveness.

- Coalitions need to mobilise around these pockets of effectiveness. Given the extent to which Ghana’s governance problems flow from the constraints that its political settlement places on elite and non-elite players acting collectively to resolve binding constraints, the role of coalitions that can bring together the ideas and agency of multiple stakeholders is critical. These coalitions need to combine top-down and bottom-up, informal and formal, political and bureaucratic.

Read the four briefing papers on Ghana

This blog originally appeared on the ESID website.

What is politics, commodification and capitalism? Tania Li visits the Global Development Institute

By Judith Krauss

What is politics? A loaded question which might draw any number of diverse and partly conflicting answers. Yet if you were indeed going to open this particular can of worms, it would be extremely helpful to have Tania Murray Li available to offer her perspective.

The Global Development Institute (GDI) did just that this week, inviting the Professor of Anthropology from the University of Toronto to give a Masterclass on ‘What is politics?’ and a public lecture on ‘Commodification, capitalism and counter-movements’. The high level of interest from staff, students and the general public in Tania Li’s visit evidences the breadth and depth of her contributions.

Two of her best-known ideas include ‘rendering technical’, which means framing problems and their solutions in a way that lends itself to technical fixes without addressing root causes, and the ‘will to improve’ capturing a host of social development aspirations. Her reflections, drawing particularly on ethnographic research in Southeast Asia, resonate with scholars and practitioners in anthropology, geography, political economy, development studies and beyond.

Given her diverse work, the Masterclass brought together postgraduate researchers and staff from GDI and beyond whose research interests are just as multi-faceted as the person they had come to exchange with, ranging from mining and CSR to youth activism in Ethiopia. It was the second Masterclass organised by the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Doctoral College, following a previous exchange with Branko Milanovic on inequality and its links to migration.

Given GDI’s focus on communicating research to stakeholders, Tania Li’s thoughts on the interface between researchers and practitioners, outlined in a 2013 paper in ‘Anthropologie et développement’, proved of particular interest. She identified three types of engagement between anthropological research and development practitioners, ranging from research in the service of big D development programming via an outright critique of such programmes, to an in-depth engagement with small d development, historically specific conjunctures and political struggles. The conversation raised questions such as whether pressures to ‘render technical’ may limit a priori the types of problems and potential solutions considered, the matter of framing research in the language of or delineation to certain stakeholders, and also yielded a wider engagement with issues of researcher positionality.

This question of researchers’ role and the politics of research proved another key interest for the early-career and postgraduate researchers assembled, with questions arising on insider-outsider relationships between researchers and stakeholders and managing expectations. Tania Li drew on her diverse experience in interacting with a broad range of stakeholders to emphasise the difference between critical engagement and passing judgement, highlighting the importance of contextualising stakeholder situations and thus engaging in critical, but non-judgemental analysis. A second key insight she raised, drawing also on David Mosse’s work, was the need to remember that taking a step back to write analytically about stakeholder behaviour is inherent in the research process and in scholars’ function of thinking critically. Howeverit also creates a distance which neither researchers nor interlocutors may have anticipated.

Tania Li’s public lecture, drawing especially on her latest book Land’s End , emphasised the need for critical reflection especially on all assumptions habitually associated with commodification, capitalism and counter-movements. Illustrated vividly through examples from two decades of ethnographic research in Sulawesi, Indonesia, she challenged the audience to engage critically with what commodification, capitalism and counter-movements actually mean and to what degree they constitute new phenomena. For instance, she emphasised that commodification, the purchase and sale of e.g. products, land or labour, is not at all a recent invention.

However, the difficulty arises when such exchanges are no longer voluntary transactions from a position of autonomy, but become compulsory for survival in the absence of any alternative. This distinction, drawing partly on Wood and Brenner, is highly relevant in differentiating commodification from involuntary forces often inherent in capitalist relations.

She vividly supported this distinction using her ethnographic research in communities living in mountainous areas in Sulawesi. Over a 20-year period, as land resources grew scarcer and pressure increased to make the most of existing plots, she witnessed first an increasing shift from food production to cash-crop cocoa cultivation and then a process of land concentration in the hands of the most capable farmers, leaving many now landless families struggling to find alternative livelihoods. Finally, she highlighted that bottom-up counter-movements against land commodification would be predicated on the presence of social organisational structures which are unlikely to exist everywhere:. actual counter-movements tend to be top-down to accommodate privileged land access vested elite or colonial interests.

Tania Li’s inspiring Masterclass and public lecture doubled as imperatives never to stop engaging critically and questioning one’s own and others’ assumptions, a call worthy of application throughout academic life and beyond.

The next Global Development Seminar is Wednesday 20 April, on ‘Understanding youth poverty in Arusha, Tanzania: Capturing economic, social and psychological dimensions’ with Dr. Nicola Banks and you can also see a full listing of our events.

Finding the business case for CSR

This post critiquing an article in Harvard Business Review article caught my attention recently. I’m catching up on old reading here but this article rehashes the perennial debate about ‘the business case for CSR’. The HBR article basically argues we’re asking too much of CSR if we’re asking it to make money:

“There is increasing pressure to dress up CSR as a business discipline and demand that every initiative deliver business results. That is asking too much of CSR and distracts from what must be its main goal: to align a company’s social and environmental activities with its business purpose and values. If in doing so CSR activities mitigate risks, enhance reputation, and contribute to business results, that is all to the good. But for many CSR programs, those outcomes should be a spillover, not their reason for being.”

The response of CSR consultant Richard Hardyment is that “This is dangerous talk” and accuses HBR (not the authors, oddly) of “winding back the clock”. That if such arguments are entertained seriously all the good work of those arguing that there is a business case would be undone. If nothing else, this demonstrates a lack of conviction that the business case is a solid one that can stand some testing and scrutiny. One of the best (titled) articles on the subject makes the argument that the fact that the business case has been debated for so long (they survey decades of research) without conclusive evidence being presented only further undermines the argument for its existence.

There is a quite remarkable volume of literature about whether CSR initiatives make money or not, and the response summarises many of the arguments, but in my experience, the business case is a central if difficult to quantify argument. And when I say central, many think that, without it, CSR initiatives in the mining industry are pretty much dead in the water. However, things are a little more complex than a simple black/white argument.

In Aseem Prakash’s pioneering work on companies going ‘beyond compliance’ in the US pharmaceuticals industry, such policies were often adopted without a clear business case being presented. In my own research in the mining industry, the language of ‘risk’ fills this gap between fuzzy, complex social world and hard numbers on the balance sheet. If you have to give away a massive mine as BHP did with OK Tedi in 2001 then CSR initiatives (and tailings management) were clearly a sensible investment. If you can get away without doing this and skirt the potential high costs of conflict, then there’s not really a ‘business case’. It’s not black and white and cannot be given a final answer, however much we may wish one. The ‘business case’ remains quite elusive and in David Vogel’s words, “niche”.

The tone of the response seems a little hysterical to me and stirs up my skepticism about whether there is something of the emperors new clothes about the universal push for CSR. The question of whether there is a business case is a perfectly legitimate one to be asked by any scholar (even those who choose overblown article titles like ‘The Truth About CSR’). That it is an uncomfortable one for those who’s livelihoods depend on it should surprise no one.

This post was first published on Tomas’ Mining and CSR blog.