Focusing on aid means we miss more effective ways to promote development

Over the last few years, UK aid has acted as a lightning rod for criticism as it has risen to meet the international target of 0.7% of GNI, while other government spending has been subject to significant reductions.

The Daily Mail in particular has aggressively pursued a campaign against the aid budget and mobilised 230,000 supporters to sign a parliamentary petition calling for the 0.7% target to be scrapped as they claim it results in “huge waste and corruption”. The petition was recently debated by a packed room of MPs, the vast majority of whom lined up to defend UK aid spending, highlighting the positive impact it makes around the world.

UK aid is some of the most closely scrutinised in the world, by various parliamentary committees and independent external bodies. The Department for International Development is a leader in aid effectiveness and transparency, which helps drive up the standards of less progressive donors. And while the £12 billion annual aid budget is certainly a significant sum, it represents just 16p in every £10 of government spending. Collectively, we throw away much more in food waste (an estimated £19 billion) than we spend in aid.

However, I’m concerned that the apparent fixation we have on the aid budget in the UK means we’re ignoring even more effective ways to help poorer nations.

The idea that development can be achieved largely through foreign aid alone has been discredited. Countries that have experienced significant improvements in the well-being of their population in recent years have largely achieved this through engaging with markets and international trade, boosted by the end of the Cold War, China’s return to the global economy and favourable commodity prices. The creation and diffusion of relatively simple technical knowledge about health, hygiene, nutrition, organization and technologies has also played an important role. While effectively given aid, provided in the right context can provide vital assistance to people in need, it cannot ‘create’ development for whole societies.

If the UK and other rich nations are serious about helping to catalyse development across the world, there are five key policy areas that require urgent attention, which I explore in depth in my new book ‘Should Rich Nations Help the Poor’:

- Reform international trade policies so that poor countries and poor people can gain a greater share of the benefits derived from trade.

- Recognize international migration as an element of trade policy and a highly effective means of reducing poverty.

- Take action against climate change (mitigation and supporting adaptation) and take responsibility for the historical role of rich nations in creating global warming.

- Reform global finance to stop the siphoning off of income and assets from poor countries to rich countries by corporations and national elites.

- Limit the arms trade to fragile countries and regions and carefully consider support for military action (budgets, technology and even ‘feet on the ground’) in specific cases, such as the successful Operation Palliser in Sierra Leone.

This holistic approach to global development is the type of response envisaged by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which the UK signed up to just last September. However a recent report by the cross-party International Development Select Committee of MPs was highly critical of the lack of any sort of joined up thinking across government on key aspects of the 17 goals

In strident tones, the report highlights “a fundamental absence of commitment to the coherent implementation of the SDGs across government.” Without a proper cross government strategy, they fear “it is likely that areas of deep incoherence across government policy could develop and progress made by certain departments could be easily undermined by the policies and actions of others.” A formal mechanism to ensure policy coherence across Whitehall is called for.

Many of the SDGs are inherently political, calling for reductions in inequality, improvements in governance and for gender equality. In many areas, national ownership by citizens and state are vital. However in other issues that go beyond aid, there’s a clear agenda for action by countries of the Global North. But it’s precisely these issues, such as international tax and trade reforms, which will be hampered without clear commitment and coordination across governments like the UK. If we continue to focus on aid alone as a proxy for development, it’s also these issues that won’t receive the attention they deserve from policymakers.

From climate change to spiralling inequality, given the challenges the world faces it’s both morally right and in our own self-interests for rich nations like the UK to help the poor. But if we’re unable to move beyond aid and properly consider the most effective ways we can help poor countries, we’ll leave a world to our children and grandchildren that’s more unstable, less secure and with more people mired in poverty than there needs to be.

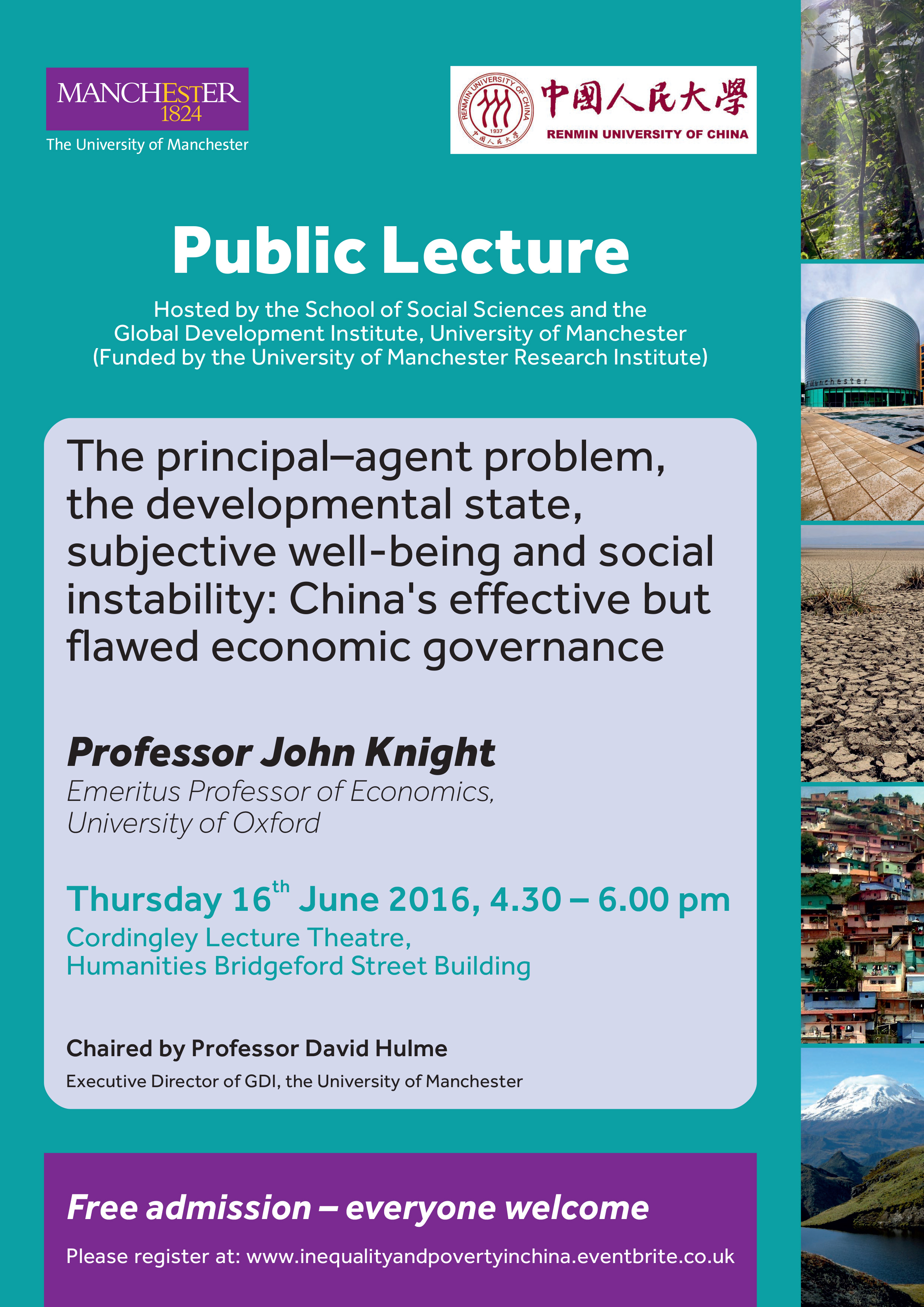

Listen | John Knight on China’s effective but flawed economic governance

Professor John Knight, The University of Oxford, recently spoke at the GDI on ‘the principal-agent problem, the developmental state, subjective well-being and social instability: China’s effective but flawed economic governance.’

Listen to the talk in full below

‘I feel trapped in limbo with my Syrian passport’

Luis Eduardo Pérez Murcia PhD researcher, Global Development Institute

The ongoing war in Syria has left millions of people in conditions of displacement either within or across national borders. Not all Syrian asylum seekers and refugees fled following direct threats and violence. As the experience of Noor illustrates, some left their country to pursue their professional and academic careers but then, because of dynamics of war, cannot not return.

This is the story of Noor, an international student who could not return to Syria because of the civil war. She is now hoping to be granted refugee status in the UK.

Noor, which in Arabic means ‘light’, came to England as an international student in 2014. By the time she arrived, the conflict in her country was being represented internationally as the ‘Syrian crises’. Coming to England has for long been an aspiration for Noor. She spent many years learning English and gaining the academic qualifications necessary to be accepted at a British university. However, she recalls that when she was accepted by The University of Manchester she was concerned about whether or not she would be able to obtain a visa, having heard that visas for Syrians, even those who are sponsored students, were being rejected. Everything worked out fine, however and Noor was able to come to England and pursue her dream of studying at a British University.

By 2015, the conflict in Syria had worsened and was no longer being described by the international media as a ‘Syrian crises’ but was being referred to as the ‘Syrian war’. Opportunities for Syrians to obtain visas were limited and millions were trapped within Syria or were able to flee to neighbouring countries. And others made the hazardous journey and tried to reach Europe by crossing the Mediterranean Sea.

Despite the escalation of the conflict, as soon Noor finished her studies she returned ‘home’ as planned. However, after only one day home in Damascus it became clear to her that what had initially been referred by international media to as an ‘uprising’ and later as a ‘crisis’ was indeed a ‘war’. Noor realised that ‘home’ was no longer a safe place in which she could pursue her dreams and achieve her aspirations. When Noor returned to England to attend her graduation ceremony it crossed her mind that England, a place in which she had had such a wonderful and productive time, could become her next home.

Noor applied for refugee status and immediately shifted from being an international student to being an asylum seeker. While waiting for the Home Office decision, and despite having the financial support of her family in Syria, Noor has been moving from one place to the other in order to keep her expenses down.

Noor’s story tells us something about what and where home is and what it means. Noor herself says that ‘home’ is a tricky concept and one that is hard to define. Ultimately she says, home is neither my country nor the physical house I was living in Damascus. Home to me is more a feeling”. Having spent a significant part of her life living in other countries including France, Saudi Arab, Lebanon and England, Noor says, “I see life as a train station. I am always ready to move”. She experiences home as a mobile space. “I feel at home in a place I like. I think family is central for my understanding of home but home is also the place you feel you can contribute the most. I am volunteering as a research assistant and bringing support to refugees in the UK, so I think England could now be my home”. She stresses that she is an independent woman able to work and contribute to this society as do other refugees. She added “If I am granted permission to stay, I will work, I will pay taxes and I will do my best to contribute to this society”.

However, waiting for the Home Office concerning her status in the UK is not free of tension and she is anxious about the future. Noor told me “I feel trapped in limbo. I am not saying I feel in limbo living in England. I can make this place my home. What I mean is that I feel trapped in limbo with my Syrian passport. I cannot work or move anywhere. [] In order to feel at home I need papers. I need the permission to stay”.

Noor’s emphasis on the need of ‘papers’ to feel at home in England can be better understood if we consider the role of the symbolic value of material things in the process of home-making. I asked Noor if she had brought anything with her to England that reminded of her home in Damascus. In response, she recounted a little story. When she had left her home in Damascus to get a job in a neighbouring country, her mother had asked her if she wanted to take something with her to remind her of her family at home. Noor had looked at her belongings and chose an envelope. This is the same envelope Noor brought to England. It contains her academic diplomas, language test results, letters of reference and her passport. When asked why she chose the envelope she simply replied “that is what I am. Thus, that is what I need to make a home for myself in this country”.

Noor’s experience is only one of millions of Syrians who have fled conflict or who cannot return to their country because of the escalation of war. Having to make a new home away is an experience shared by many of the over 60 million people currently living in conditions of displacement across the world.

Today, in celebrating the Refugee Day, the narrative of Noor calls our attention that refugees, as Maja Korac stresses, are ordinary human beings living in extraordinary circumstances. They are just people like us trying to find a safe place to live in the world.

Will small development charities survive?

Yesterday the Global Development Institute’s David Hulme represented a research project run jointly by GDI and SIID (the University of Sheffield), at the Small Charities International Development Debate in the House of Lords. The research project is seeking to map and give insight into the operations of and relationships within the UK-based international development NGO (INGO) sector.

Hosted by the Foundation for Social Improvement (FSI), the debate was part of FSI’s Small Charity Week, and asked ‘will small international development charities survive?’ David took the affirmative, as did S.A.L.V.E. International CEO Nicola Sansom and SNP National Secretary and Westminster Spokesperson on International Development Patrick Grady. On the opposing team were campaigner, writer and consultant on NGO strategy Deborah Doane, and founder and CEO of Teach a Man to Fish, Nik Kafka. The debate was chaired by Bibi Van der Zee, Editor at the Guardian’s Global Development Professional Network.

Speaking first, Nicola Sansom pointed out that small INGOs are risk-takers, have low overheads and develop and maintain strong networks. She also noted that increasingly affordable comms routes mean costs are less of a barrier to awareness-raising, and also make it easier for charities to exercise transparency with donors and other stakeholders. David also made a case for small INGOs’ capacity for networking and partnerships, pointing out that they play an important role in connecting complex debates at an interpersonal, community level and in diversifying ‘official’ development messaging and activity. He argued that plenty of donors are still looking to engage with small INGOs in their capacity as an important, active component of civil society. However, as the current SIID & GDI mapping research has so far shown, David acknowledged that the biggest 9% of UK NGOs receive 90% of all development spending, and that if small charities are to survive there exists a clear need for better distribution of funds.

The SNP’s Patrick Grady argued that small INGOs can and should survive, and therefore that they will. He emphasised that there will always be a desire amongst people at the grassroots to contribute to humanitarian causes, as donors and volunteers. He also noted that the larger INGOs often rely on smaller partners for actual, in-country project delivery, concluding that there is certainly a need for flexibility and adaptability as the development sector continues to change, but that its reforming will include big opportunities for small INGOs.

The opposition presented some convincing counterpoints, with Deborah Doane taking the stance that small charities are unlikely to survive in their current form. She made the point that NGOs and donors alike are feeling the financial pinch, and that, generally speaking, philanthrocapitalists tend to push small INGOs to operate as social enterprises not charities, and in so-doing undermine the charity model. She also noted a growing hostility toward donors on the part of recipients in the Global South, and a desire amongst the latter to take ownership of their countries’ development needs. She summarised by saying small INGOs won’t survive as they are today because of: the changing funding environment; the global assault on civil society; and the fact they’re ‘too damn authentic’.

Nik Kafka agreed that the current funding environment is not conducive to the survival of small charities; donors are increasingly ‘honing in’ on causes with very specific mandates (such as ‘educating girls in Uganda’), rather than more general approaches that allow for a wider range of small INGOs to benefit. He also argued that the costs of conclusively monitoring and demonstrating impact are rising. Similarly, while technology is generally cheaper now, it is still costly to purpose-build tools (like apps) that could improve operational efficiency; funds that small INGOs don’t tend to have. Conversely, he did make the point that while big INGOs may be good at securing donor support, they don’t always have the specialist knowledge needed for effective project delivery.

Ultimately, there was general consensus that there is a future for the small charity cohort, but that adaptability and an openness to working collaboratively are crucial. It was noted by FSI co-founder and Chief Executive Pauline Broomhead that networking is a strength for many small charities, but not all are as good at developing these connections into active collaborations and partnerships.

The debate provided compelling context for the SIID and GDI mapping project. Research is still in progress, but has produced interesting preliminary findings, including that:

1. Growth of the sector was most vigorous in the mid-2000s. But it is premature to view current (downward) trends as indicative of a long term decline in vigour of growth in numbers of organisations

2. The development sector is substantial, with expenditure equalling approximately 50% of current ODA

3. Distribution of expenditure is highly unequal, with less than 9% of organisations accounting for nearly 90% of expenditure (and 1% accounting for 50% of expenditure)

4. The sector has experienced growth generally, but the largest organisations experienced a dip in expenditure in 2012. Smaller organisations have experienced a decline in expenditure in recent years

5. Change in expenditure is highly variable, with the smaller organisations most likely to experience declines from one year to the next

More information on the project is available at on the Mapping Development NGOs website.

Small Charity Week was first established by the Foundation for Social Improvement (FSI) in 2010, to celebrate and raise the profile of the small charity sector. The week is one of a series of activities and initiatives to support and raise awareness of the hundreds and thousands of small charities that, every day, make a huge difference to vulnerable communities right across the UK and the rest of the world. Thank you to the organisers for their work, and what was a thought-provoking event!

Blog by Sarah Illingworth for SIID.

Should the UK abandon aid?

A petition organised by the Daily Mail calling for an end to the 0.7% aid spending target will be debated in parliament today after gaining 230,000 signatures.

In his new book, ‘Should Rich Nations Help the Poor’, Professor David Hulme examines the increasingly polarised debates around aid. He concludes that while we must be mindful that aid spending alone won’t end poverty, effectively given aid is both morally right and in the self-interest of a rich nation like the UK.

In a new video, he argues that UK aid is some of the most well scrutinized in the world and that working in fragile states like Somalia or Afghanistan are inherently risky – but hugely important.

Buy Should Rich Nations Help the Poor? from Wiley for £7.49, using the discount code: PY724.

Should Rich Nations Help the Poor?

GDI Executive Director, Professor David Hulme, has written a short and accessible analysis of why and how rich nations should help poor people and poorer countries. The book is ideal for general readers and students new to Development Studies and is available from Wiley for £7.49, using the discount code: PY724.

GDI Executive Director, Professor David Hulme, has written a short and accessible analysis of why and how rich nations should help poor people and poorer countries. The book is ideal for general readers and students new to Development Studies and is available from Wiley for £7.49, using the discount code: PY724.

1.2 billion people still live in extreme poverty and around 2.9 billion cannot meet their basic human needs. We know that foreign aid is necessary, but not sufficient to end global poverty. Spiralling inequality and the growing impact of climate change on poor people threatens to derail the progress that’s been made over the last 25 years.

Hulme explains why helping the world’s neediest communities is both the right thing to do and the wise thing to do – if rich nations want to take care of their own citizens’ future welfare.

The real question is how best to provide this help. The way forward, Hulme argues, is not solely about foreign aid but also trade, finance and environmental policy reform. But this must happen alongside a change in international social norms so that we all recognize the collective benefits of a poverty-free world.

“David Hulme has provided an invaluable primer on why and how we should help the poor of the world. He rightly sees the key issues as climate change and inequality. In the end, we are all in this together, rich and poor alike.” Angus Deaton, Princeton University and Winner of the 2015 Nobel Prize in Economics

Global production networks and social upgrading: emerging research on a persistent challenge

Dr Rory Horner, Global Development Institute

In a global economy increasingly structured through global production networks, existing public and private governance approaches are struggling to promote improved labour conditions and sustainability, while new challenges are also emerging.

With this in mind, the Global Development Institute’s (GDI) Global production networks, labour and trade research group hosted a workshop earlier this month on “Global value chains and social upgrading”, to take stock of this field and to bring together a group of more than 20 emerging scholars to discuss their recent research on this issue. The workshop was generously funded by the Brown International Advanced Research Institute (BIARI) Alumni Research Initiative, as follow-up support to alumni – GDI’s Rory Horner and Rachel Alexander, GDI alumni Shamel Azmeh, Fabiola Mieres, Vivek Soundararajan and Annika Surmeier – of their fantastic two-week annual summer school which focuses on addressing global issues. The GDI also provided considerable support, with Manchester having led much of the growing field of research on social upgrading in global production networks, notably through the Capturing the Gains project.

In her opening keynote plenary on “Global value chains, market-making and the rise of precarious work”, Jennifer Bair traced cases of precarious work from New York city a century ago to contemporary Bangladesh to highlight how outsourcing through global value chains gives rise to challenging labour conditions.

Within global value chains, private governance has proliferated in recent years, and Greg Distelhorst, Judith Stroehle and Scott Sanders all sought to explore the impacts of, and limits to, compliance with private standards. Samia Hoque provided evidence from her recent collaborative paper on Bangladesh.

Gale-Raj Reichert’s work on the electronics industry, Vivek Soundararajan’s work on sourcing agents and boundary work and Annika Surmeier’s work on tourism presented further examples of labour challenges across a variety of sectors.

Fabiola Mieres provided an alternative notion to corporate-driven mechanisms through a notion of “worker-driven social responsibility”, while Matthew Alford highlighted public-private governance challenges in South African fruit. Indeed the challenges for both public and private governance was a recurring theme in the workshop discussions.

As public governance attempts at addressing social upgrading issues, international trade agreements are also now including social standards, as highlighted through Mirela Barbu’s work on the European Union’s Free Trade Agreements, and Shamel Azmeh’s presentation on the case of the Jordan-US trade agreement.

Prospects for social upgrading must consider gender, power, and embeddedness, as highlighted through Nikita Pardesi’s work on oil and gas in Trinidad and Tobago, Eleni Sifaki’s work on grape production in Greece and Judith Krauss’s recently completed doctoral research on sustainability challenges in the cocoa sector.

The challenges for better social outcomes in GPNs also go beyond labour. Anke Hagemann explored the impact of participation in GPNs on urban areas, while Rachel Alexander demonstrated the difficulty UK cotton-garment retailers face in promoting sustainability in their extended supply networks from India.

At the same time, new challenges for social upgrading emerge. The growth of transnational online labour markets within “virtual production networks” warrants growing attention as Alex Wood highlighted. Now more than ever, in today’s increasingly multi-polar global economy with growing South-South trade, social upgrading must also be considered beyond end markets in the global North. Jinsun Bae’s work on Myanmar’s garment industry, Corinna Braun-Munzinger’s work on corporate social responsibility in China and Natalie Langford’s work on social standards and tea production in India all made this case.

Workshop participants received detailed feedback and had opportunities to discuss their work with leading scholars in this field – Jennifer Bair (University of Colorado-Boulder), Peter Lund-Thomsen (Copenhagen Business School) and Andrew Schrank (Brown) as well as Manchester’s own Stephanie Barrientos, Martin Hess, and Khalid Nadvi.

With continued challenges for both private and public regulation of labour and sustainability issues in the global economy as well as new challenges emerging, the debate must continue. Look out for the research of these emerging scholars we hosted at GDI as it pushes this conversation forward.

Motorbike scheme breaks cycle of unemployment in Tanzania

An innovative ‘revolving motorcycle project’ set up by the Tanzanian Federation of the Urban Poor and supported by an academic at The University of Manchester is helping a group of young men in Arusha find new opportunities.

Dr Nicola Banks, of the Global Development Institute (GDI) has been working in Arusha, northern Tanzania, researching the social impacts of youth unemployment. After seeing first-hand how young people were struggling to earn a living, Nicola decided to do something to help.

Youth unemployment is a big problem in Tanzania. In the low-income community where Dr Bank’s research is based, around 70% of young men lack stable jobs.

One of the most popular ways for young men to earn a living is by becoming a Piki Piki (motorbike taxi) driver. But most drivers do not own their own motorcycles outright, instead spending a majority of their weekly earnings on renting their vehicles. This can cost around 6000 Tanzanian shillings a day (£1.85), leaving the drivers with very little money to live on, let alone save for longer term goals.

Dr Banks, an ESRC Future Research Leader at GDI, learned about the value of revolving loan funds through being exposed to the work of Shack/Slum Dwellers International whose Tanzanian affiliate, the Tanzania Federation for the Urban Poor, supported by the NGO, Centre for Community Initiatives is involved with her research. It was easy to share the idea with a local Piki Piki driver who was struggling to save money for university.

She said: “My research in Arusha shows above all that life is incredibly tough. It is an ongoing struggle for young people. I was lucky enough to meet an inspiring young man called Bakari who was well educated, very hardworking and had grand plans. But I was frustrated after the meeting as I knew unless there was a radical change in his life, there wasn’t going to be anyway he could meet those plans.”

Working with the SDI Federation in Tanzania and another NGO Tamasha Vijana who specialise in participatory development with young people, Bakari and some of his fellow Piki Piki drivers designed a revolving loan fund drawing on the capacities of the organized urban poor especially the women’s federation leadership. SDI’s experience with revolving loan funds has developed from its commitment to community empowerment and the first schemes were designed by women pavement dwellers living in Mumbai in the 1980s. Such designs can be understood as blending asset transfer programmes, traditional savings groups and social enterprise models. They are now illustrating a new and innovative model for working with young people in Tanzania which builds on similar schemes elsewhere in east Africa such as motorcycle group in Jinja recently visited by GDI students on fieldwork.

Along with Executive Director of the GDI, Professor David Hulme, Dr Banks personally donated the group’s first motorcycle. Now the project is up and running, the group has purchased their second motorbike and are close to buying their third. Long term, the scheme has the potential to triple the take-home income of the drivers, allowing them to plan and invest for the future.

Dr Banks said: “The concept of the savings group is simple. The first member receives a motorcycle and puts the 6,000 shillings usually spent on rental into a group savings account instead. Once there is enough money to purchase a second bike, two drivers then save until there is enough to buy a third and so on.

“Once all six members of the savings group own their own bike they continue to save until a seventh motorcycle is bought. This motorcycle is passed onto another savings group for the process to start again, potentially making it a scalable and sustainable business model.”

Bakari said: “I have always struggled with my life, but life always goes on. I have never stopped struggling and that is why I joined this project. But now, in my community, I am a role model. I am confident, I am no longer afraid of life. My life is my own responsibility, and not that of anyone else.” These sentiments echo those of the Federation who believe that development will be secured through self-reliant projects that build the strength of the community and enable them to engage with the government to get the infrastructure and services they need to advance their needs and interests. And this includes seeking more capital to replicate schemes such as this through the Federation’s loan fund, Jenga.

Every year an estimated 800,000 young men and women enter the labour market in Tanzania. These include school and college graduates and people who have migrated to urban areas from the countryside. The University has produced a short film about the scheme, its impact on the community and its potential for the future.

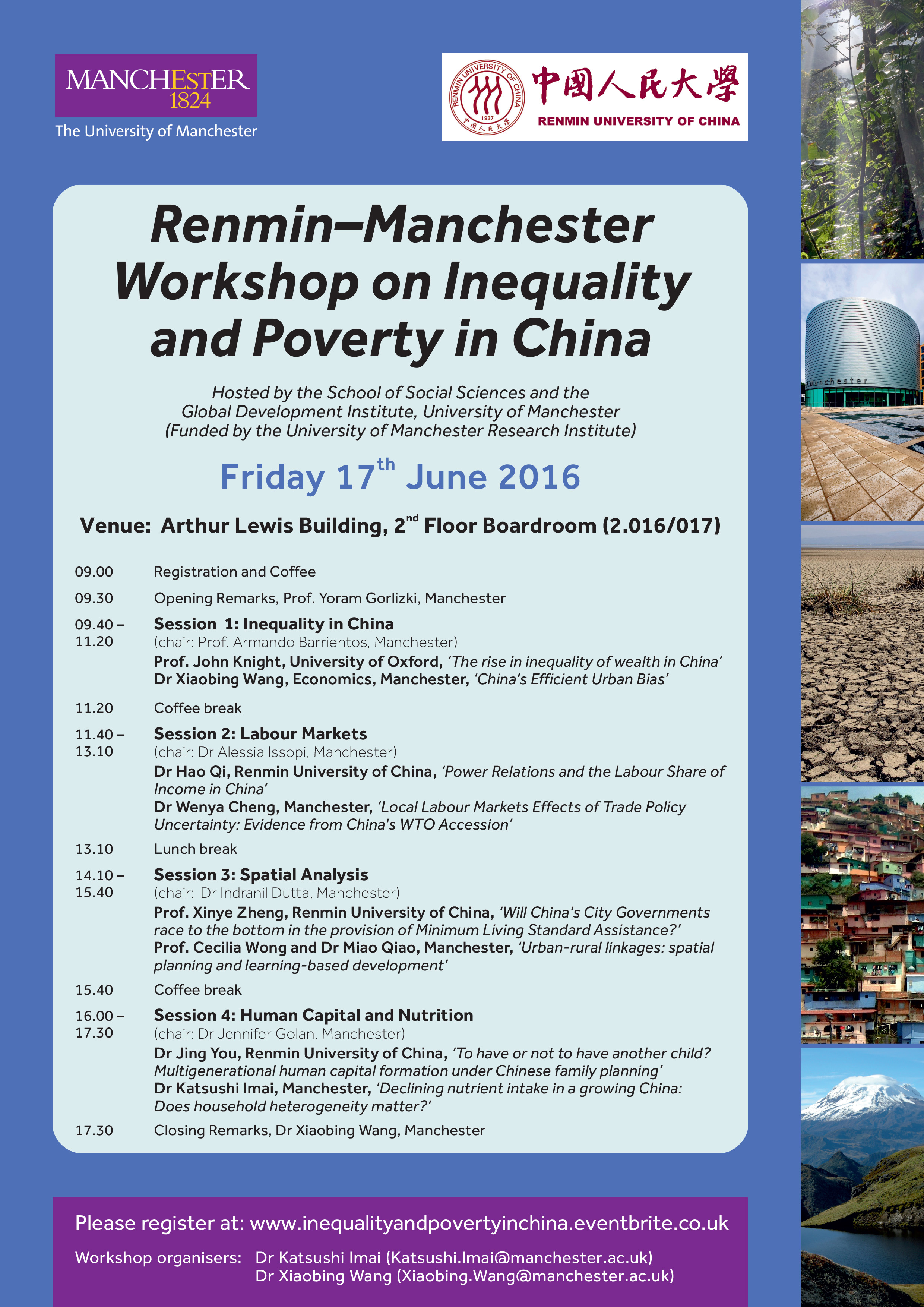

Renmin–Manchester Workshop on Inequality and Poverty in China

Will consumers change the world? A GDI masterclass with Tim Bartley

Corinna Braun-Munzinger, PhD researcher at the Global Development Institute

Does it make you feel good to know that all coffee sold at the university cafeteria is fair trade certified? Did you feel less comfortable about buying that £3 T-shirt when you saw the media reports about 1100 workers dying in the Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh a few years back? And have you ever stood in the supermarket wondering if it is worth paying double the price for organic tomatoes? If your answer is yes to any of these questions, then you seem to be what Tim Bartley and his co-authors call a ‘conscientious consumer’.

During a Masterclass organised jointly by the Global Production Networks, Trade and Labour research group and the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Doctoral College, we (a bunch of PhD students and academics passionate about finding out how to address sustainability in global production) had the chance to discuss with Tim his new book “Looking behind the Label”. In the book, the authors describe that sustainability labels such as fair trade or organic have seen a boom in the US and in European countries over the past years. They show how conscientious consumption relates to some individuals’ postmaterialist values, as well as to a number of wider societal factors, such as the structure of the retail sector – for example, it is easier to buy fair trade chocolate if your regular supermarket stocks it than if you have to go to a special ‘one-world shop’ to get it.

During a Masterclass organised jointly by the Global Production Networks, Trade and Labour research group and the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Doctoral College, we (a bunch of PhD students and academics passionate about finding out how to address sustainability in global production) had the chance to discuss with Tim his new book “Looking behind the Label”. In the book, the authors describe that sustainability labels such as fair trade or organic have seen a boom in the US and in European countries over the past years. They show how conscientious consumption relates to some individuals’ postmaterialist values, as well as to a number of wider societal factors, such as the structure of the retail sector – for example, it is easier to buy fair trade chocolate if your regular supermarket stocks it than if you have to go to a special ‘one-world shop’ to get it.

Tim Bartley and colleagues also go on to question whether conscientious consumerism is a good thing to improve social and environmental sustainability of production. On the one hand, it may show that people are more aware and put pressure on brands and retailers to improve sustainability – but on the other hand, conscientious consumerism could actually be counterproductive if it distracts from other options of political engagement or obscures governments’ responsibility for some of these issues. So there are two ways of looking at the rise of conscientious consumption.

The great thing about the book is that it does not stop there, but brings together the discussion on conscientious consumers with an analysis of the effectiveness of sustainability standards and labels used to certify the products that conscientious consumers buy. For example, does it actually make a difference for conserving the rainforest if you buy a roll of toilet paper with the Forest Stewardship Council label printed on it? To answer that question, the authors draw on case studies in food, paper, garments, and electronics. They show how sustainability standards and their effectiveness are strongly influenced by the specific characteristics of sectors and products, but also by the agendas of different actors involved in shaping these standards. Overall, their conclusion is a weak defence of conscientious consumerism: Conscientious consumption can make a difference sometimes and under some conditions. But it is certainly no panacea, and additional ways need to be found to address persisting unsustainable models of production in the global economy.

Many of us researchers in the Global Production Networks, Trade and Labour research group work on issues closely related to Tim’s book. Many of us have first-hand experience of trying to make sense of sustainability standards in food, garments or electronics in our PhD research and beyond. Coming together with Tim in a small masterclass setting was a great opportunity for each of us to raise burning questions, get feedback and discuss in an informal setting with a leading expert in the field.

Going beyond the book, participants in the masterclass seemed particularly interested in exploring the roles of Southern consumers and emerging Southern sustainability standards, as well as the interactions between private standards and domestic governance on working conditions global production. Conveniently, Tim is currently working on another book on transnational governance that digs deeper into several of these aspects… expect more in 2017. We were fortunate enough to get an outlook on this project – and another opportunity to ask questions – in Tim’s afternoon lecture at GDI. In case you missed it, listen to the podcast below.