Moving up the ladder: How does India do in social mobility?

By Kunal Sen, Professor Of Development Economics & Policy, Global Development Institute

By Kunal Sen, Professor Of Development Economics & Policy, Global Development Institute

A question of long-standing interest among social scientists is the degree to which an individual’s status in society is determined by the position of one’s parents. In egalitarian societies, where you are in the social and economic status ladder should not be principally determined by your parent’s income, educational level or occupation. Social mobility research has been concerned with intergenerational occupational mobility, but much of this research has concentrated on advanced market economies. However, this question is of crucial importance in the developing world, and especially in emerging economies which have undergone modernisation as they have opened up to the world economy in recent decades.

Together with my co-authors Vegard Iversen and Anirudh Krishna, I look at this question in the context of India, a country which has witnessed rapid economic, political and social change since the 1980s. Using a nationally representative data-set – the Indian Human Development Survey of 2011-2012, which has detailed information on the occupations of fathers and sons, we find a relatively high degree of social mobility among urban residents in India, with around 26 per cent of sons whose fathers were in the lowest occupational class – construction workers and other labourers able to achieve the highest two occupational classes – clerical workers and professionals. However, the degree of social mobility is far lower in rural India – only around 10 per cent of the sons of fathers in the lowest occupational class could achieve the highest two occupational classes.

More disturbingly, we find significant differences in social mobility by social group in India – Dalits (or Scheduled Castes) and Adivasis (or Scheduled Tribes) are the most disadvantaged social groups in India, with high rates of poverty, and these two social groups see very low rates of social mobility as compared to forward castes in India. For instance, only 11 per cent of Dalits and 9 per cent of Adivasis whose fathers were in the lowest occupational class could achieve the highest two occupational classes, while 25 per cent of forward caste individuals could. This suggests that barriers to occupational mobility still persist in India’s most disadvantaged social groups in spite of widespread affirmative action programmes and intense political mobilisation of these groups since independence.

We also find that for India’s historically disadvantaged communities, the high risk of a sharp descent in the occupational ladder, where the son ends up in the lowest occupational class when the father is in the highest two occupational classes, is between 3.5 and 4 times higher than it was in Victorian Britain. In contrast, for a forward caste son residing in urban India, the sharp descent risk is on par with the corresponding risk in Victorian Britain. Finally, we find striking parallels between upward mobility prospects and sharp descent risks in India and China, two societies which differ greatly in terms of their social and political structures as well as their rates of economic and social development. Reversing these trends in the world’s two most populous countries is essential for greater equality of opportunity and a fairer society in China and India.

David Hulme looks ahead to the DSA Conference in September

David Hulme, Executive Director, Global Development Institute

I am just back from Japan – a delightful visit with colleagues in Nagoya and Tokyo. The only cloud, in a very sunny week, was hearing about the scale of public support for a populist, nationalist right-wing party in Japan. Does this sound all too familiar…the UK, France, the Netherlands, Austria…and over to Donald Trump in the US? Our theme at the DSA Annual Conference is ‘Politics in Development’. Much of the agenda is about the politics of developing and emerging countries, but we shall have to allocate time to asking about what is happening to ‘politics’ in the rich world – as it has very big implications for international development and increasingly these seem to be turning negative.

This year’s conference is all set to be a very productive three days. Its sessions look at the big issues and challenges of international development and, alongside these, at detailed work on theoretical, methodological and applied topics. Outside of the sessions there are great opportunities for informal discussions in Oxford’s many cloisters, cafes and bars.

But, what a difference a year makes! Last year at the Development Studies Association 2015 conference at Bath there was an air of cautious optimism about the global context for making the world a somewhat fairer place and tackling poverty and inequality. The Sustainable Development Goals were about to be unveiled in New York – very long, and very long-winded but reflecting deep discussions by all UN member states: a real step forward for global democratic deliberations. Arrangements for the Climate Change talks in Paris were making good progress according to the ‘sherpas’ setting up the negotiations. Europe was having problems with ‘migrants’, but Angela Merkel was encouraging EU governments to fully honour their UN commitments to supporting refugees and helping migrants.

In mid-2016 things look very different and an air of deep pessimism and/or profound precariousness is evident. For those of us who are UK citizens (and especially for people working in universities) the Brexit vote means that the future is very unclear. Isolationism, protectionism and xenophobia seem to be the values that are sweeping around the UK…and Europe…and further afield. For many involved in teaching and research on international development the public popularity of such values, and associated policies, challenges many of the values that have underpinned the promotion of development – international cooperation, economic and social integration, welcoming people from other parts of the world, global social justice and human rights.

But, we need to rise to this challenge…and perhaps take some responsibility for it. Have we, as academics, teachers and researchers, focussed our work on those who think like us and neglected our role as contributors to ‘public understanding’? Could we have done more…and can we do more in the future…to help our fellow citizens and people in other countries understand that in the 21st Century we all live in one world. If we want an international environment that is stable, prosperous and sustainable for ourselves and for future generations then, as Angus Deaton writes, we (humanity) “are all in this together”.

There will be lots of opportunities to discuss our detailed work at the Conference and also to think about what DSA members and DSA as an organisation can do to help public understanding in the UK of the need for collaboration and cooperation between people and countries. Please do some thinking in advance and come prepared – what can we in DSA (as individuals and as an organisation) do to make Brexit less damaging for international development?

Could you also put a little thinking into ‘whom’ you would like to elect to DSA Council to represent your views? There will be several positions coming vacant this year and we need energetic and committed members to join the Council. Please send nominations to our Secretary, Fiona Nunan before the Conference.

The Power Dynamics of Big and Open Data

Richard Heeks, Professor of Development Informatics, Global Development Institute

At a recent CDI brown-bag discussion on data-intensive development, we hypothesised a mirror-image power dynamic between big data and open data.

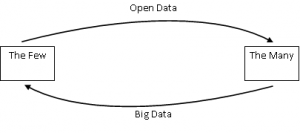

Open data has an inherent tendency to redistribute power from the few (who originally hold the data) to the many (who can now access the data). It supports sousveillance. Big data has an inherent tendency in the opposite direction. It gathers data about the many but only the few have the power to capture, store, process, interpret and use that big data. It supports surveillance.

The extent to which these are inherent affordances of these data systems vs. the extent to which these tendencies are inscribed into those data systems is a matter for further debate. But what it does suggest is that big data per se is more reproductive than transformative of power inequalities within society. Think of the way in which major users of big data – social media platforms, e-business multinationals, telecommunication companies – operate. Their uses of big data reinforce inequality much more than they challenge it.

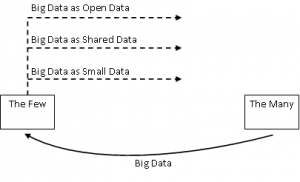

One way to address this is to reverse the power dynamic flow shown above: big data must become open data. This could happen in various ways:

- Big data as open data: big datasets are made openly available online in accessible format (as in all cases, with due consideration for data privacy and security).

- Big data as shared data: big datasets are made available to particular organisations (e.g. those of civil society).

- Big data as small data: sub-sets of big datasets are shared with the sources of that data for their use (e.g. the particular communities or groups from which the big data derived).

But what will make a reversal happen? To understand this, we need to study open data motivations: what causes organisations to open their datasets? Reviewing our knowledge of open data, we could not find examples of intrinsic motivations driving adoption of open data. Instead, drivers to opening of big datasets seem likely to be extrinsic:

- For public sector owners of big data, domestic political economy (e.g. local campaigns for access to data; economic benefits from creation of a local data economy) and external political economy (e.g. encouraging foreign investment through a reputation for openness).

- For private sector owners of big data, government regulation to force opening of datasets, or shareholder/consumer pressure.

Without such extrinsic pressures and the openness that ensues, big data may not deliver its developmental potential.

David Hulme at Japan International Cooperation Agency

On Wednesday, 27 July 201, Professor David Hulme, Executive Director of the Global Development Institute spoke at the Japan International Cooperation Agency. His presentation focused on the ideas detailed in his latest book, ‘Should Rich Nations Help The Poor?’ You can view his presentation in full below,

Listen | Professor Sam Hickey at Australia National University

Effective States and Inclusive Development (ESID)Research Director Professor Sam Hickey delivered this seminar to The Development Policy Centre at Australia National University on ESID’s research. Which forms of politics matter most, how can these be conceptualised and what kinds of policy implications flow from thinking politically about development?

A Research Agenda for Data-Intensive Development

Richard Heeks, Professor of Development Informatics

In practice, there is a growing role for data within international development: what we can call “data-intensive development”. But what should be the research agenda for this emerging phenomenon?

In practice, there is a growing role for data within international development: what we can call “data-intensive development”. But what should be the research agenda for this emerging phenomenon?

On 12th July 2016, a group of 40 researchers and practitioners gathered in Manchester at the workshop on “Big and Open Data for Development”, organised by the Centre for Development Informatics. Identifying a research agenda was a main purpose for the workshop; particularly looking for commonalities that avoid fractionating our field by data type: big data vs. open data vs. real-time data vs. geo-located data, etc; each in its own little silo.

A key challenge for data-intensive development research is locating the “window of relevance”. Focus too far back on the curve of technical change – largely determined in the Western private sector – and you may fail to gain attention and interest in your research. Focus too far forward and you may find there no actual examples in developing countries that you can research.

In 2014 and 2015, we had two failed attempts to organise conference tracks on data-and-development; each generating just a couple of papers. By contrast, the 2016 workshop received two dozen submissions; too many to accommodate but suggesting a critical mass of research is finally starting to appear.

It is still early days – the reports from practice still give a strong sense of data struggling to find development purposes; development purposes struggling to find data. But the workshop provided enough foundational ideas, emergent issues, and reports-back from pilot initiatives to show we are putting the basic building blocks of a research domain in place.

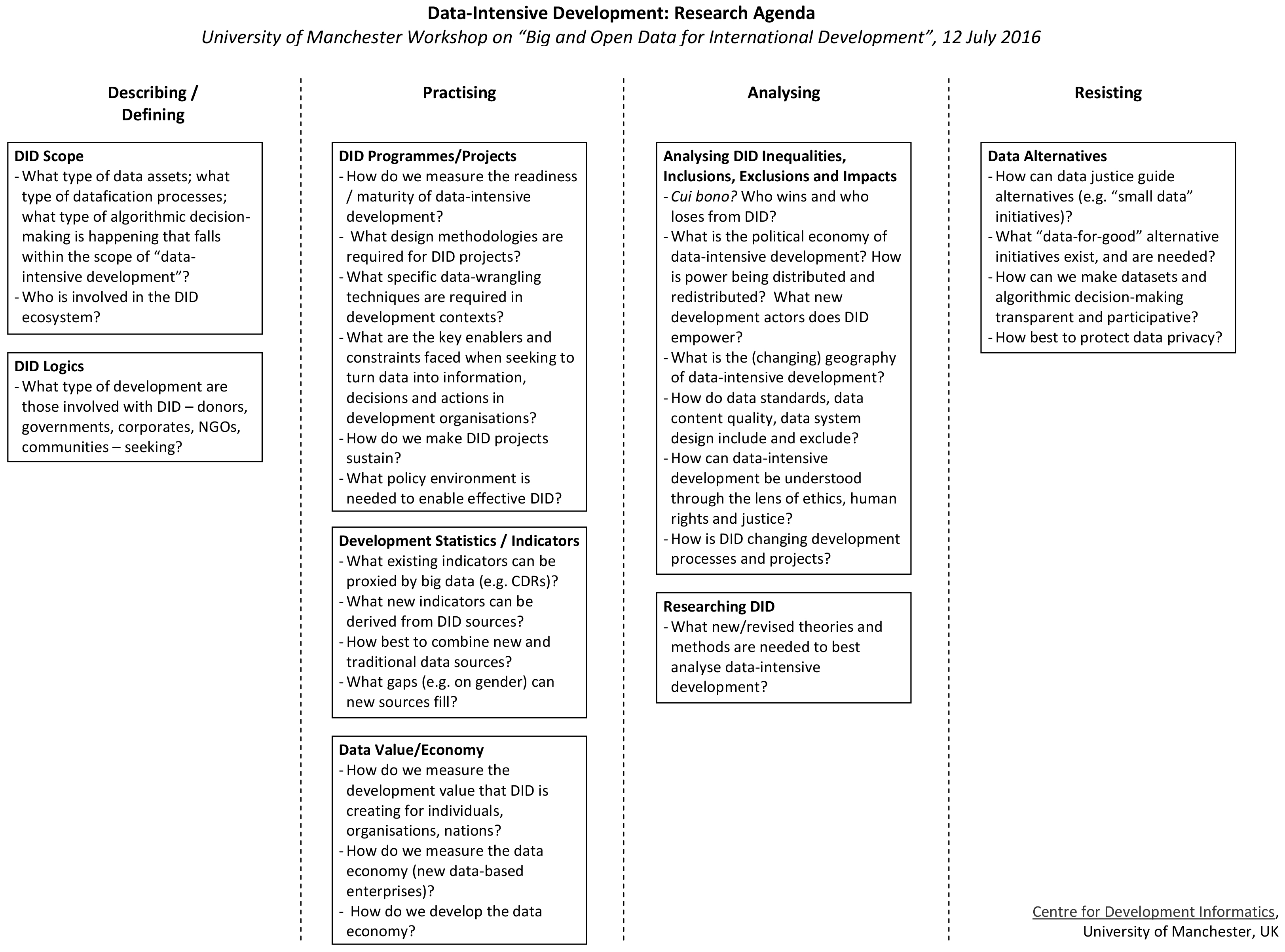

But where next? Through a mix of day-long placing of Post-It notes on walls, presentation responses, and a set of group then plenary discussions[1], we identified a set of future research priorities, as shown below and also here as PDF.

The agenda divided into four sub-domains:

- Describing/Defining: working out the basic boundaries, contours and contents of the data-intensive development domain.

- Practising: measuring and learning from the practice of data-intensive development.

- Analysing: evaluating the impact of data-intensive development through various analytical lenses.

- Resisting: guiding practical actions to challenge potential state and corporate data hegemony in developing countries.

Given the size and eclectic mix of the group, many different research interests were expressed. But two came up much more than others.

First, power, politics and data-intensive development: analysing the power structures that shape DID initiatives, and that are inscribed into data systems; analysing the way in which DID produces and reproduces power; analysing what resistance to data hegemony would mean.

Second, justice, ethics, rights and data-intensive development: determining what a social justice perspective on DID would mean; analysing what DID can contribute to rights-based development; understanding how ethical principles would guide civil society interventions for better DID.

We hope, as a research community, to take these and other agenda items forward. If you would like to join us, please sign up with the LinkedIn group on “Data-Intensive Development”.

[1] My thanks to Jaco Renken for collating these.

Alumni profile: Chris Foster

We heard that one of our alumni was coming back to Manchester to attend the Big and Open Data Workshop this month, so we sat down with Chris Foster to talk about how why he chose to study at the University of Manchester and what he’s been up to since he graduated.

Why did you choose to study at the University of Manchester?

There are a lot of great experts at the University of Manchester who look at intersection of ICT, digital technology and development, and that really attracted me – the opportunity to work with these world renowned experts. I’m also a big fan of Manchester, I really like the city!

What did you do after graduating?

I spent a little bit of time at the University of Manchester, developing some of the work I had done for my PhD. I then got a postdoctoral position at the University of Oxford, doing research in a similar area for nearly two years, before finding a lecturer position at the University of Sheffield.

What are you doing now?

I work at the University of Sheffield’s Information School, which explores social science around information, information technology and data. I’m really interested in how digital technologies are being used in various contexts, but particularly around firm contexts, and how firms are globalising, how they’re using digital technologies to help them globalise, and what are some of the advantages and disadvantages of that. I think this is an important research area at the moment as the internet and digital technologies are becoming more prevalent.

How has your University of Manchester degree helped you?

In two areas: first of all, in terms of thinking critically. When I first came to the University, I was interested in technology and development but I don’t think I had really understood or explored these topics in a critical way – the Master’s degree definitely gave me that. When I moved on to do the PhD, being able to plan and put into action an innovative programme of research was something that I was able to learn how to do with the support of the staff at GDI, and that has been a very valuable skill to learn.

What’s your best memory from the University of Manchester?

There were a couple of really fun memories: it was great when I finally submitted my PhD after all that time working on it, what a relief! The graduation itself was really good fun – there were four or five of us who had been together in the department for a few years, and we were able to come together to celebrate what we’d been able to achieve, which was a really nice experience.

What advice would you give to students?

Often when you finish you PhD, it can be quite a struggle to figure out what to do next – you’ll have been doing your PhD for quite a number of years so working out what to exactly to do after it can be difficult. This is particularly true when you’re looking to work in academia: it can be hard to move up that ladder to go from your PhD to become a lecturer, so there may be a period when you perhaps move around a bit to find something that fits suitably to what you’re interested in.

Another good piece of advice is that whilst you’re doing your PhD, there’ll have been a great number of academics and colleagues you’ll have interacted with, and these are great people to stay in touch with and possibly work and collaborate with in the future

Parliamentary book launch asks, “Should Rich Nations Help the Poor?”

Professor David Hulme with Rory Brooks CBE of the Global Development Institute’s philanthropically-funded Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Doctoral College

Giving a gathering of over 20 development professionals, journalists, alumni and MPs a reminder that 1.2 billion people went to bed in extreme poverty last night, Mike Kane MP opened up Professor David Hulme’s book launch at Westminster for a frank but positive discussion on how and why rich nations should help the poor.

Introducing the Global Development Institute (GDI) and its Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Doctoral College as a world leading research institution, the MP handed over to Professor Hulme who talked about his new book – Should Rich Nations Help the Poor? – within the context of Brexit and the decisions that need to be reached which will influence UK international development policies.

“It is a moral responsibility for rich nations to help the poor and, additionally, it is in their self-interest. If we are thinking of our own future, and our children and grandchildren, then we need a prosperous and stable world,” said Professor Hulme.

Addressing the issue of how we can help, Professor Hulme talked about how the traditional answer of foreign aid is not enough. We are now in a “post-aid world” where aid is still important, but makes up a smaller part of the answer. Instead, he argued for the need to reform international trade policies, so poor people and poor countries get a greater share of the benefits derived from trade; stopping illicit financial flows that siphon off income and assets from poor countries to rich countries by corporations and national elites; and, rapid action to reduce greenhouse emissions from rich countries and the provision of adaptation finance and technology to poor countries.

Another topic covered was the rise in inequality in many countries. This slows down poverty reduction and social progress and increasingly threatens to give political control to ‘the 1%’ who benefit excessively from economic growth and wealth creation. In many rich countries people have a diminishing belief that the lives of their children would be better than their own – this is a sentiment which has been fanned by populist leaders to blame ‘migration’ for problems that are actually caused by inequality. Global inequalities will have to be tackled if the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are to be achieved by 2030.

“If you are worried about economic migrants from Africa then you have to address inequality. If you consider the pay and opportunities of people living in Africa, then why would they stay in poverty and not move for a better life? We need to worry about job creation and pay in Africa.”

You can buy a copy of Professor David Hulme’s Should Rich Nations Help the Poor? now.

See live tweets from the event below

#ShouldRichNations Tweets

Call for Postdoctoral Fellowships as part of the Global Challenges Research Fund

The Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the North West Doctoral Training Centre (NWDTC) have issued a call for Postdoctoral Fellowships as part of the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF).

This career opportunity emphasises impact and stakeholder engagement activities which build on candidates’ prior PhD research. Key points to note are:

- At the time of submission, applicants must either have a PhD or have passed their viva voce with only minor corrections, and have no more than three years of active postdoctoral experience.

- The proposed fellowship activities must be ODA compliant.

- The call is open to those who have completed a PhD within any institution of the North West DTC, i.e. Lancaster, Liverpool or Manchester Universities.

- The deadline for applications is 9 September; fellowship start dates are between November 2016 and January 2017.

- If you are interested in applying for this opportunity with the Global Development Institute as a hosting institution, please let us know by e-mailing judith.krauss@manchester.ac.uk – we will run a support session in early August.

Please find more details here.

Call for abstracts/presentations on ‘Mobile Technology for Agricultural and Rural Development in the Global South’

A call for abstracts/presentations on ‘Mobile Technology for Agricultural and Rural Development in the Global South’ has been issued.

The aim of the 20 October 2016 Workshop is to share research and practice on current trends in ‘Mobile Technology for Agricultural and Rural Development in the Global South’: specifically to bring together researchers from diverse disciplines with practitioners who have experience of implementing mobile applications and agriculture information systems in differing country contexts. We hope the workshop will shape a research agenda and form the basis for future research and practitioner partnerships.

Prospective presenters should submit an abstract of 200-400 words outlining their proposed paper or presentation to: mobileagworkshop@gmail.com with a deadline of 31 July 2016.

If you have any questions, please contact the workshop organiser: Dr. Richard Duncombe, Centre for Development Informatics, University of Manchester, UK richard.duncombe@manchester.ac.uk