Dan Brockington, Nicola Banks, Mathilde Maitrot and David Hulme

One of the vices of poverty is not being able to access that little bit of extra money when you need it. An opportunity comes up, such as a job interview, or a useful animal you can buy, but you do not have the savings to make best use of it. The inevitable happens (relatives get married) and you cannot contribute to the celebration expenses. A tragedy strikes, such as illness, and you cannot raise the funds to deal with it. Your capacity to cope with these problems is made further complicated by the fact that, given your low income, you tend to be over-exposed to them. Alternatively a little bit of extra money can ease the expenses of being poor. The poorest families pay to save money, they pay more for basic goods (as they only purchase in small quantities), they pay very high interest rates (>100% interest on loans). But whether for major events or everyday needs, part of the condition of being poor (as research on financial diaries shows) is simply not having the liquidity – the disposable cash – that you need, when you need it.

Microfinance was intended to be revolutionary because it promised to tackle exactly this. Poor people would be able to access funds in the form of small lump sums because they could call upon their friends and relatives, who knew their risk profile rather intimately, to act as guarantors. They could then invest these loans in different small business projects, or else in just the easing the day-to-day grind of getting by. The crises of liquidity could become surmountable.

But that promise of microfinance remains unfulfilled in two respects. First, in terms of its operation it does not necessarily reach really poor families. These are, after all, the riskiest groups to lend to. It is all too easy for microfinance groups to support loans to their richer members and exclude the poorest. Gradually, over time, microfinance lending groups can themselves exclude poorer families – and the loan officers who run the group, and managers of those loan officers allow that to happen.

On the other hand, the counter-veiling tendency is that microfinance companies face severe pressures to increase the number of clients on their portfolio and make a profit. This means focussing on microcredit (rather than savings) and aggressively selling loans to the wrong people who can take on debt they are unable properly to cope with. This is particularly apparent when loans are made only to women (a common practice in many instances) who are encouraged (or forced) by male relatives to take the loans, then forced to hand the money over to men who have no intention of repaying. Once again this practice is overseen by loan officers and driven by incentives and governance by microfinance managers.

Another way of putting these points is that the performance of microfinance staff must matter a great deal for the success of the organisation and implementation of its policies. We hope that you are thoroughly unimpressed by this point. It should be plain obvious. The importance of ‘HR’ and staff management was discovered decades ago. One of the reasons why management and business schools prosper around the globe is because good leadership of companies, and the people who work in them, is really important. Employees matter for organisational performance.

But if our previous paragraph was unsurprising and banal it makes the persistent absence of research into performance within microfinance organisations rather strange. While there are some authors who explore this topic, it is not a popular one in the microfinance literature. Indeed much of the microfinance research industry is founded on the assumption that organisations are homogenous and can be treated as single entities. Researchers instead concentrate on the three axes of difference that have dominated research up until this point: the nature of the clients, the broader economic and regulatory environment that surrounds them, and the sorts of loans, or products offered.

We think that more attention is needed on the work and performance of microfinance staff in microfinance research. An analogy of a play may be helpful here. Any actor will tell you that the audience (clients), stage (environment) and the quality of the dialogue and plot (products) are all important elements in any good performance. But the same actor is also likely to insist that the actors’ own work (the organisation’s staff), as well as their stage direction and production (the organisation management), also matter a great deal. We do not think that enough attention has been given to variation of performance within organisations in the microfinance community.

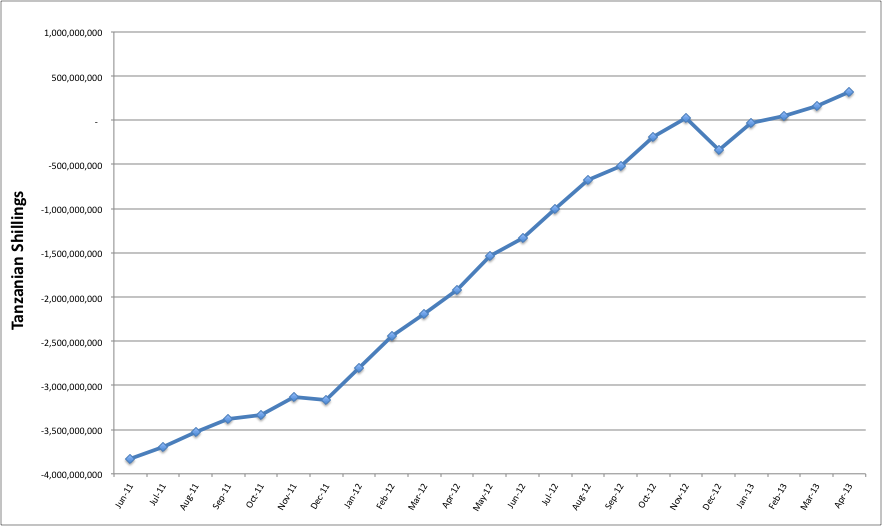

We have recently published a paper which illustrates the central importance of understanding diversity of organisational performance. We studied the success of BRAC’s microfinance scheme in Tanzania. BRAC originates in Bangladesh. It is the largest and one of the most successful NGOs in the world and has recently set up operations in a number of African countries. On the surface the microfinance scheme in Tanzania has been phenomenally successful, lending to tens of thousands of Tanzanian women. It had rapidly become the largest organisation of its kind in the country (as the graph below shows), at a time when most other microfinance organisations in the country were not growing. We wanted to understand why.

Cumulative surplus from BRAC microfinance loans

The dips in surplus every December reflecting the annual write-off of bad debts that can accrue. The exchange rate at the time of the research was approximately $US1: 1,700 Tanzanian Shillings.

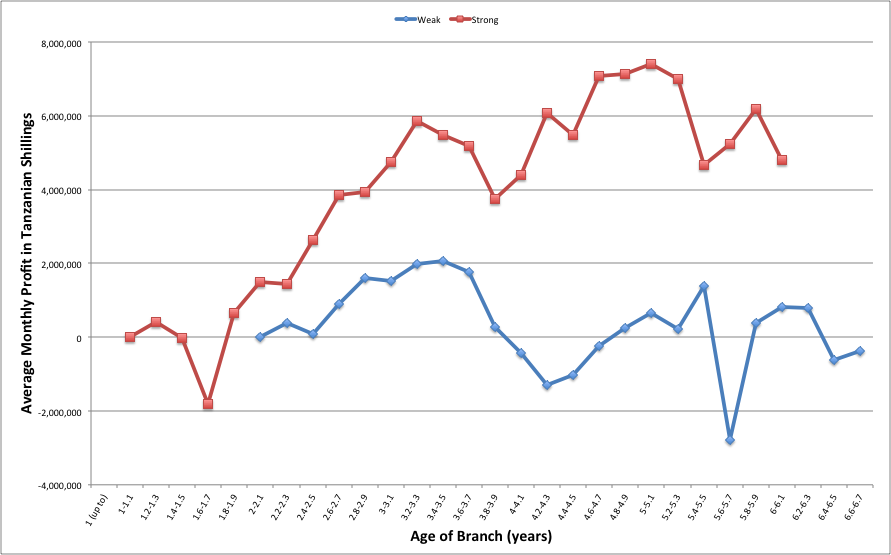

However we came to realise that there was not, in fact, a single story to be told about that organisation, rather there were several. Branch performance varied considerably (as the next graph shows), and seemed to reflect the influence of strong or weak area managers. This seemed to reflect the fact that BRAC seems to have been good at winning clients, but not necessarily at retaining them. This in itself was strange as many of the senior staff marvelled at the business acumen of their Tanzanian clients. Yet there were too many microfinance groups which were disintegrating and staff who were leaving. We felt that this reflected processes of institutional learning that BRAC and its (mostly Bangladeshi) senior management had to go through in order to understand how to operate in Tanzania, and to work with, and promote, Tanzanian staff. Shortly after our work was completed there was a complete overhaul of the upper levels of management with many more Tanzanian staff promoted, and trained for promotion. We suspect that this will make it easier for BRAC to perform better in the country.

Average monthly surplus of weak (n=28) and strong (n=32) branches over time

The dip in surplus in Weak groups at 5.6 years is due to a write-off of bad debt in the Zanzibar branches.

But the main point we want to make here is that diversity of performance within microfinance organisations matters. It has been neglected and this could cause problems later. For example, the current swathe of randomized controlled trials (RCTs – and see here or here for an interesting critique of them) hinge on robust designs that can construct sufficiently large samples to explore the impact of explanatory variables. However if important explanatory variables are omitted then RCTs may be poorly designed. It follows that, if organisational heterogeneity has not been adequately factored into RCTs, so therefore their power will be reduced. It also means that, in order properly to cope with organisational variety, RCTs will become larger and yet more expensive.

This neglect of diversity also runs counter to good practice in understanding development challenges. It becomes difficult to search for the positive outliers, and understand what makes them a success, if our conceptual frameworks does not allow for diversity, difference and outliers in the first place. We look forward to more explorations of diversity and heterogeneity within microfinance organisations, in order that the products they offer can be better delivered to the clients who need them despite the environmental challenges they face.

This blog also appeared on the SIID website