Since May 2015 we have been recording the daily money transactions of up to 70 households living near a small market town in central Bangladesh. These ‘daily financial diaries’ shed light on the money-management behaviour of low-income households, described in papers which can be found on the project’s website. Up to now we have explored matters that face all our ‘diarists’, such as savings and credit, income and expenditure, health, and education.

‘Tracking transactions, understanding lives’ is a new series focusing on individual diarists. We aim to create vivid pictures that give readers a sense of what these lives are like. We hope this will help researchers and activists design better interventions for low-income households.

Razaana

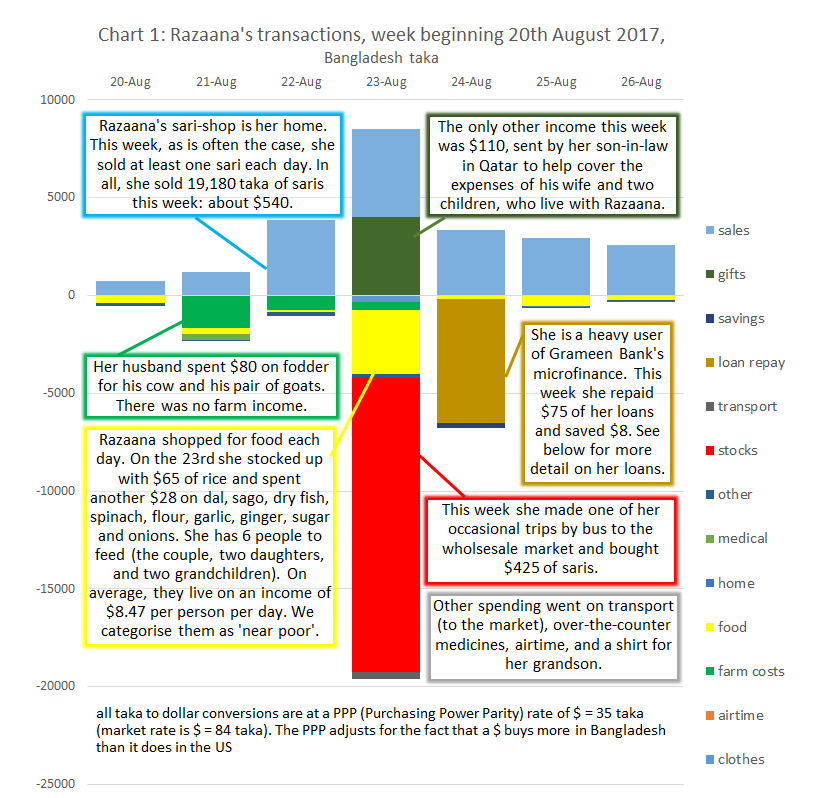

We have been interviewing Razaana (not her real name) daily since September 2015. Now in her early fifties, she is married with four children and eight grandchildren. Her husband, who is not well, raises livestock, but most of the household’s income comes from Razaana’s sari business, and she is the one who manages the family’s cash. To get a first flavour of her life, we have a chart that explores all the transactions she made in a typical week in August 2017.

As the chart suggests, Razaana is an energetic woman, and very much the driving force in her household. She was born into a modest farming family but when she was two her mother died and her father ‘went to pieces’. She was brought up by a brother, but they survived only by selling off the family land, piece by piece until there was nothing left. Razaana never went to school, and at 12 started work as a housemaid. Three years later her brother found her a husband, a dirt-poor farm labourer. Her mother-in-law treated her as an orphan and was very kind to her, and Razaana’s self-confidence began to grow. She persuaded her husband that they should move back to her own area, which was closer to a town, and there she started her sari business, surprising herself by becoming good at it. She’s also good at raising cows, though she pretends that that’s her husband’s work.

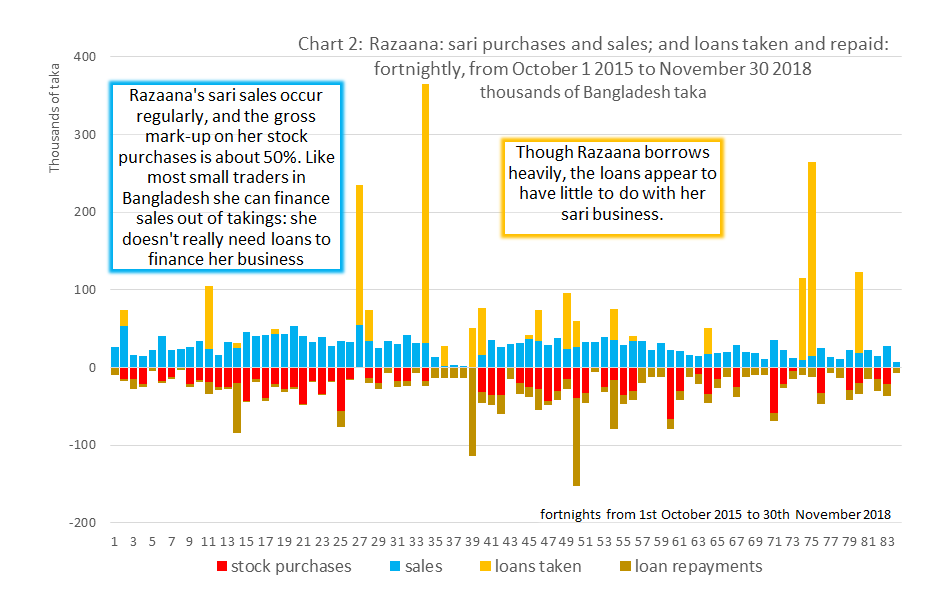

One of her assets is her excellent memory. She keeps only mental accounts of her sari business but knows the dates and balances-owing of up to 50 credit customers. She has used the same skills in her 25 years of dealings with Grameen Bank, where she was an early ‘member’. She soon became a ‘centre chief’, responsible for credit discipline in her 40-woman group, making herself indispensable to the Grameen field officers and then exploiting that position for all her worth. Two further charts explore her loan transactions (with Grameen and with private informal lenders) and show how they relate to her business and family life.

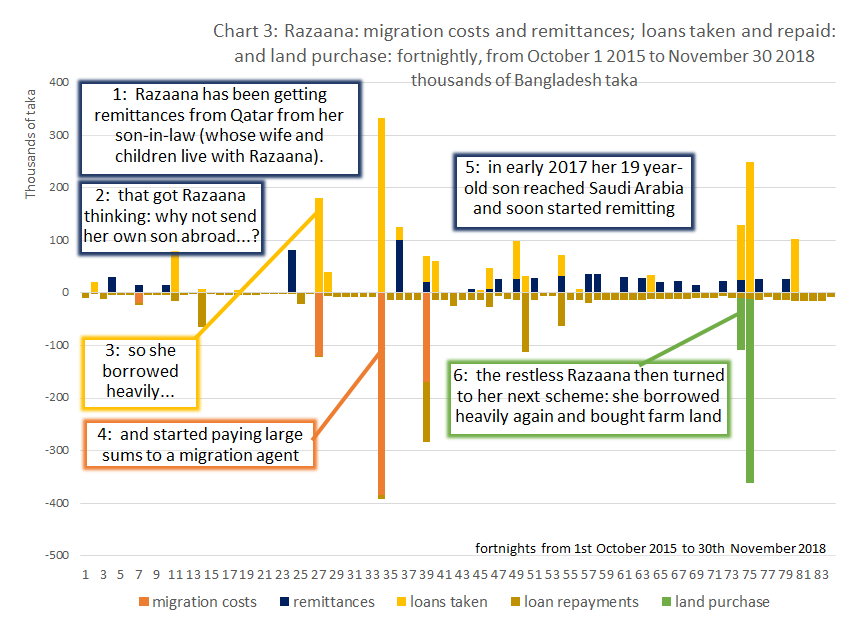

Razaana bought 1.47 million taka of sari stocks in the period and sold them for 2.23 million (about $63,000). In the same time she borrowed 1.5 million taka (of which just over a million came from Grameen) and repaid 1.1 million. She has a large outstanding balance as a result of recent loans. Though she told Grameen Bank that she was borrowing for her sari business (and Grameen staff were very happy to believe her) the loans are not strongly related to the business. Our data reveal other things going on in her life. We show them in chart 3, which keeps the loan data from chart 2, but drops the sari business flows: instead, we show remittances from abroad, the costs of sending someone abroad, and land purchases.

What is remarkable about Razaana’s borrowing is its efficiency: both for sending her son abroad and for buying land she obtained funds quickly and spent them immediately. Her standing at Grameen is so high she was able to persuade the bank to lend to her two daughters and to three compliant neighbours as well as to herself, and then used the money herself. Some of these loans were ‘cow fattening loans’ – special 6-month term loans designed for raising cows for the Eid festival. No matter, the money went on migration costs and land. Her prowess at Grameen gave her credit-worthiness with private lenders, who were also willing to chip in funds.

And so our picture of Razaana takes shape. This is an illiterate woman who still lives in a very modest village home of timber and tin-sheets, with a kitchen on the veranda, but whose ambition and energy have propelled her into a successful sari business. We looked on as she decided to send her son abroad and saw it to completion in record time. Now she’s branching out into farm-land ownership.

She tells us her plan is to keep working as long as possible, in order to rebuild the house for her son. She wants her grandchildren to be well educated. She thinks her daughters’ lives will be similar to her own. But she believes her grandchildren’s lives will be quite different, and she’s planning their education accordingly.

Stuart Rutherford

Hrishipara, Bangladesh, November 2018

The Hrishipara Financial Diaries Project is currently being funded by the UNCDF SHIFT Programme based in Dhaka Bangladesh, and we are grateful for their support.

The Hrishipara Financial Diaries Project is currently being funded by the UNCDF SHIFT Programme based in Dhaka Bangladesh, and we are grateful for their support.

Read more analysis based on the Hrishipara Diaries:

- Hrishipara daily financial diaries: Tracking transactions, understanding lives part 1

- How are Digital Financial Services used by poor people in Bangladesh?

- What the poor spend on health care?

- How the poor borrow?

- What do poor households spend their money on?

- Tracking the savings of poor households

- When poor households spend big

- When poor households spend big part 2

- Poverty measurement using data from the Hrishipara daily financial diaries

- Receiving Gifts in Low-Income Households