Khalid Nadvi, Professor of International Development, Global Development Institute, University of Manchester

5 April 2025

As financial markets across the world continue to reel from the tariffs imposed by President Donald Trump on April 2nd – so-called ‘Liberation Day’ – questions arise if this is the end of the era of globalisation and of global value chains? And, more particularly, who are the winners and losers from this process? In this brief note, I will argue that global value chains are far from dead, but they will be radically restructured because of this process. In terms of winners and losers, while it is hard to assess accurately who is most affected, many least developed countries are especially badly hit, with significant consequences for poverty.

The April 2nd announcement has completely up-ended a process that goes back to the post-war era, and was led in large measure by the United States, to develop a multi-lateral rules-based system to reduce barriers to trade and promote global economic growth. Before I turn to the consequences of this, I’ll provide a quick review of economic history is required to highlight how Trump’s policies reverse over 70 years of trade policy.

The growth of globalised trade

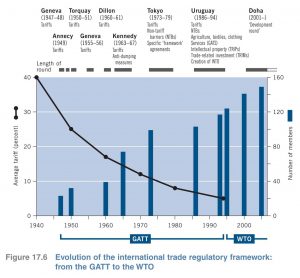

As the chart below (from Dickens 2011:534) shows, multilateral trade diplomacy, initially through the United Nations General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) and its successor the World Trade Organisation (WTO) has focused on ways to reduce tariffs and promote international trade and economic growth. This took place through various trade rounds – starting from Geneva in 1947-48 to the last and never completed Doha (Development) Round of 2001– where tariffs and trade rules were negotiated with a view to seeking greater liberalisation of trade. Each round of GATT and subsequently WTO trade negotiations brought in more and more countries in long and ever-more complex multilateral trade negotiations. Because of this process, international trade mushroomed. The 1950s through to the early 1970s was labelled in the US as the ‘Golden Age’ with rapidly rising real incomes and employment.

The 1973 oil price shock led to a new era of globalisation and the emergence of ‘global value chains’ through which ‘lead firms’ (multinational corporations and global retailers) sought to enhance their efficiency and competitiveness by seeking out lower cost production locations by sourcing from a myriad of globally dispersed suppliers. The process also brought about efficiencies and accelerated product and process innovations as specialist suppliers emerged and lead firms focused on the ‘core’ competences.

In a world of growing international competition, clear winners emerged. At the heart of this were major American financial, manufacturing and retailing giants who not only led this process of globalisation but were some of the biggest beneficiaries. Thus, the most notable winners were owners of US capital – shareholders, pension funds etc who saw their stock values rise, and US consumers who found cheaper and cheaper goods and services with rising quality and technological innovations. But there were losers from this economic and trade dynamic in the developed world, particularly workers and their families in sectors that saw firms and jobs moving to the global South. The resentment from this process has driven the politics that motivates many populist politicians on both sides of the Atlantic. In some parts of the developed world former industrial heartlands were able to regenerate themselves, often with supportive government policies to enter new more value-added activities, including in the services sector, generating new jobs and higher incomes. In other areas, industrial rustbelts emerged, heightening regional inequalities within developed countries, with declining hope and growing anger within communities that were unable to re-structure and re-organise in the face of the new world order.

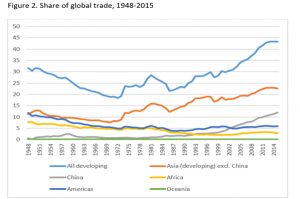

Over the past 50 years, an integrated world of trade and services has emerged. For parts of the developing world, trade-led growth offered an opportunity to economically advance, improve incomes, raise employment and address poverty. The developing world’s share of global trade rose from less than 20% in 1972 to over 40% by 2015. At the core of this were East Asian countries – initially south Korea and Taiwan and subsequently China. Trade as the development strategy became part of the accepted view and both the US and the European Union – as the then-leading global markets – offered low-income countries preferential market access through reduced tariffs via initiatives like the EU’s Everything but Arms Agreement (EBA) and the US’ African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA).

Source: Horner and Nadvi (2018).

Will tariffs kill global value chains?

Global value chains now dominate across all major sectors, from commodities, agro-foods, manufactured goods and services. President Trump seeks to reverse this process, and through the imposition of tariffs force US firms to reshore their supply chains to rebuild the US’ manufacturing base. Is this likely to happen? Maybe, but maybe not.

Many commentators have already questioned the rather spurious basis on which the US’ new tariff regimes have been calculated. What Trump lists as the tariffs that other countries impose on the US is completely wrong. His calculations of tariffs imposed on the US is based on a calculation of the trade deficit that the US has with those countries. This does not reflect tariffs. Tariffs are taxes imposed on imported goods. Trade surpluses and deficits arise from economics of comparative advantage and the competitive behaviour of firms and farms. The rather non-sensical view that the US tariffs will lead to an autarkic world of US manufacturing fails to understand how integrated we are today and shows how little the Trump Administration seems to understand global trade dynamics. The only sense behind their thinking seems to be that these rather spuriously calculated tariff restrictions will lead not only to a process of re-shoring of value chains back to the US by US and international firms but also force individual countries to negotiate with Trump one-by-one – to do his so-called ‘deals’.

Can reshoring take place, and if so, over what time scale? To address this one has to look at individual sectors to understand how those industries are globally organised and the industrial and financial engineering needed to reshore complex supply chains. In relatively low-skilled labour-intensive industries, capital can be relatively more footloose and production can be shifted from one location to another over a relatively short period of time (2-3 years, perhaps). In high skilled and capital-intensive sectors this can take a lot, in fact a lot, lot, longer. We are talking of 5-10 years, or even more. However, what will happen in the short term is that costs for US consumers will go up rapidly, while many developing country suppliers will find that they are further squeezed as lead firms seek to push some of the tariff costs down the value chain.

Winners – and losers

Who wins and who loses from this process? In the US we can already see the outcomes playing out. In the two days of global financial trading since the April 2nd announcement it is estimated that close to US5 trillion has been lost in market capitalisation, and this bearish trend is likely to continue into next week. So, owners of capital (which includes tens of millions of ordinary people in the US and globally with their savings and pension pots held in stock markets) have lost already. In a matter of weeks, US consumers will see rising prices in the shops as the tariff costs are passed down by importers and – given the complex and widespread nature of global value chains – few goods and services will be immune from these price shocks. Similarly, investors and consumers across other parts of the world will feel the shock. The prospect of a global recession is a real concern.

Amongst US firms the impact will be differentiated. Those firms that have already diversified their markets globally may well be less affected than those who have continued to rely on supplying the US. The sports good and clothing brand Nike, for example, which relies heavily on supply chains from China, Vietnam and other parts of Asia saw its stock value fall by 14% the day after tariffs announcement. At the same time, though, around 60% of Nike’s sales are outside the US, which might give it an opportunity to pivot its marketing operations. However, if the tariffs lead to a trade war, which looks like a very likely outcome, then an economic recession across many parts of the world will push incomes and spending down.

More specifically, some of the hardest hit through this turmoil are going to be the poor in some of the poorest countries on the planet who had begun to build an industrial manufacturing base via exporting to the US through preferential trade access. Take the case of Lesotho, which has seen its import tariffs to the US rise from 0% to 50%. Lesotho’s major industrial sector, and its biggest employer, is its largely Chinese and Taiwanese-owned clothing industry which has been supplying the US market thanks to the AGOA trade preferences. The US is its biggest trading partner and the vast bulk of its exports to the US is clothing. Over 80% of the Lesotho clothing production goes to the US, sourced by leading US retailers. The clothing sector, with over 35000 workers, is the biggest manufacturing employer in the country. With an overnight tariff jump to 50%, Lesotho’s clothing industry is effectively dead.

Some firms may shift sales to the South African market, but that is tiny in comparison to the US. Most of the foreign owned firms in Lesotho will look to move to other locations where tariffs are relatively lower and where a similar labour and supply base can be found. Kenya, for example, will be a likely winner with only 10|% tariffs. But for Lesotho’s clothing sector workers there is no upside. Layoffs, unemployment and poverty looms. What deal can Lesotho offer to Trump? Real estate? Will this lead to reshoring of volume clothing production back to the US? Not likely, unless US consumers are willing to pay much higher prices for their garments given the labour costs differentials between US workers and those in places like Lesotho. Similarly, in Southeast Asia, low-income countries like Cambodia (with 49% tariffs) or Sri Lanka (44% tariffs) will see their major clothing sectors move to other regional locations. India’s clothing sector with only 10% tariffs could be a possible winner.

Across sectors there will be different outcomes. Labour-intensive sectors, such as the global garments industry, where capital can move relatively quickly between countries, will see tariff-hopping strategies adopted by GVC lead firms as they seek out suppliers in countries with only the baseline 10% tariff. In the short term, costs will rise for consumers as new GVC linkages are built, while developing country suppliers and their workers will feel a greater supplier squeeze as lead firms seek to push some of the tariff costs down the value chain. In the more capital and knowledge intensive sectors, such as electronics and automotives, particularly where GVCs rely on Chinese and East Asian suppliers the impact will be greater and longer term. Reshoring these sectors back to the US will be challenging, and in many areas infeasible.

South – South dynamics

There is another major global shift in the geographies of globalisation that commentators have failed to notice. And this shift predates Trump’s announcement. In aggregate terms, since the mid 2000s, the global South (namely the developing world) does more of its international trade with other countries in the developing world than it does with the global North. Much of this is linked to the Chinese market – and China’s voracious appetite for the raw materials and commodities, but also its rapidly growing middle class. China is already the biggest global market for automobiles and electronics. And other parts of the global South (the so-called BRICS members) are emerging as major consumer end-markets in their own right.

Since the last Trump presidency, China has forged various bilateral trade agreements with regional and global South partners, while its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative has built a wide array of infrastructure and industrial projects across Asia, Africa and Latin America. China has used trade and investment linkages as part of its geo-economic diplomacy strategy. For much of the global South, while China maybe a competitor, it is also a more reliable partner. What Trump’s irrational actions (and not just on trade, but on international security, the wipeout of USAID, and continuing erosion of judicial processes and the rule of law) does is to heighten the long-term decline of the United States and the relative rise of China.

We will see a more challenging environment for much of the developing world, but at the same time we are already seeing the contours of a new world order emerging. And in this new geography of globalisation, global, regional and domestic value chains will remain as a core feature of industrial organisation. As we brace ourselves for continuing global economic instability in the coming days and weeks, the question is whether politics will trump economics or the markets (and consumers) will force Trump to reassess his strategy. At the end of the day though, Trump’s tariffs have only served to accelerate moves to new global economic order that will shape the contours of future globalisation and global politics.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Please feel free to use this post under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Full information is available here