Over the last 12 months, researchers at GDI and the South Asian Network for Economic Modelling (SANEM) have been exploring some of the effects of the “twin crises” in Bangladesh: the Covid-19 pandemic and the recent rise in the cost of living. This project is part of the Covid-19 Learning, Evidence and Research Programme in Bangladesh, which is managed by the IDS and funded by the FCDO.

Written by David Fielding, Professor of Development Economics, GDI

The starting point for our research was a survey conducted by SANEM in 2018, covering 10,500 households from all parts of Bangladesh. The survey used a stratified sampling design to ensure that the results were nationally representative.

Towards the end of 2023, we revisited 9,065 of these households to conduct another survey and discover how they had fared over the past five years.

Here, we summarize some of the initial results of our survey. Detailed analysis of the data is still ongoing.

How is household poverty measured?

A major part of our research explores how rates of poverty have changed in different parts of Bangladesh and among different types of households.

Here, “poverty” includes not only monetary dimensions such as household consumption, but also non-monetary dimensions such as education and health. Results from the household survey allow us to measure and analyse different dimensions of poverty, and to construct multi-dimensional poverty indices that summarize the overall level of deprivation of individuals and households.

Measures of multidimensional poverty based on previous surveys indicate that between the early 1990s and the late 2010s, the incidence of poverty in Bangladesh was falling at a rate of about three percentage points per year, on average.

How have things changed over the last five years?

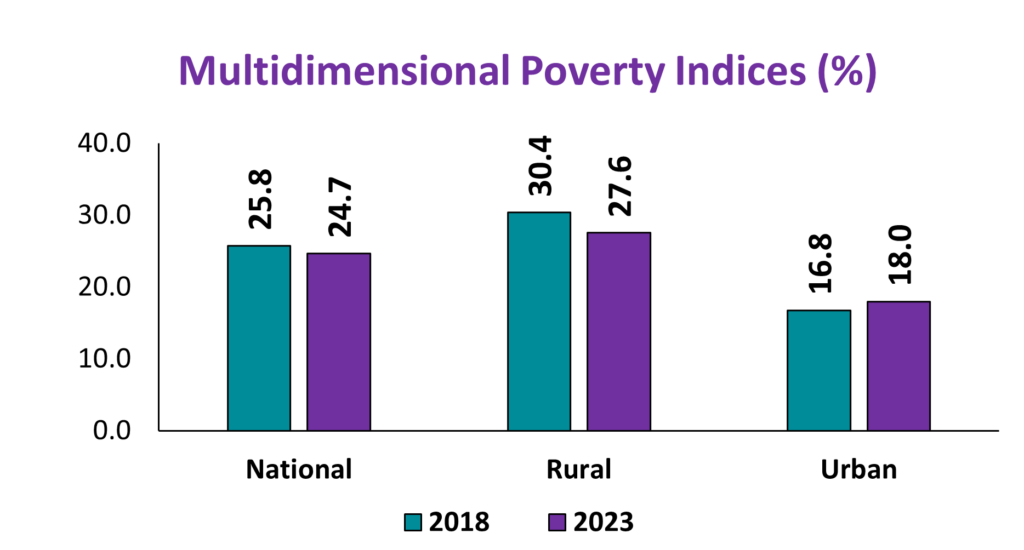

When we measure the incidence of poverty among households in our survey using a standard multidimensional measure, we find that there has been a small reduction in overall incidence over the last five years.

Digging deeper, we find that the incidence has fallen somewhat more in rural areas (although the rate of decline is much less than three percentage points per year), while rising in urban areas. This confirms evidence from other studies that the pandemic and cost of living crisis have been associated with a group of “new urban poor”.

Whilst the results of a comprehensive analysis of the causes and consequences of these trends will be discussed in a later post, we will now highlight some of the factors that are related to the recent slowdown in Bangladesh’s progress in the elimination of poverty.

Multiple factors influence Bangladesh’s ability to eliminate poverty

Increase in male unemployment rate

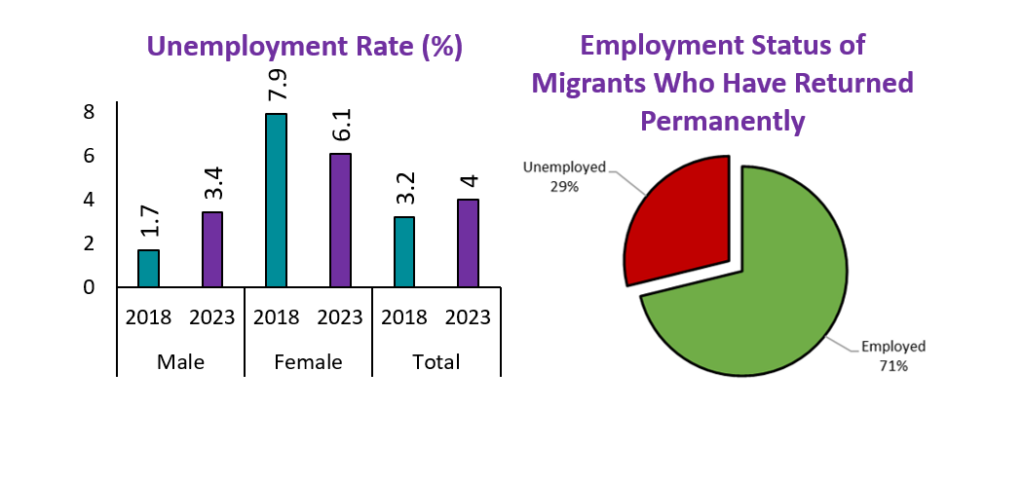

First, Bangladesh has a very large number of migrant workers: both international and internal migrants. Many of these migrants lost their jobs during the pandemic, and our 2023 survey finds that by the end of 2023, 29% of them were still unemployed. Unemployment among male migrants likely explains a large part of the doubling of the male unemployment rate over the last five years, although this has been partly offset by a fall in the female employment rate.

Access to education

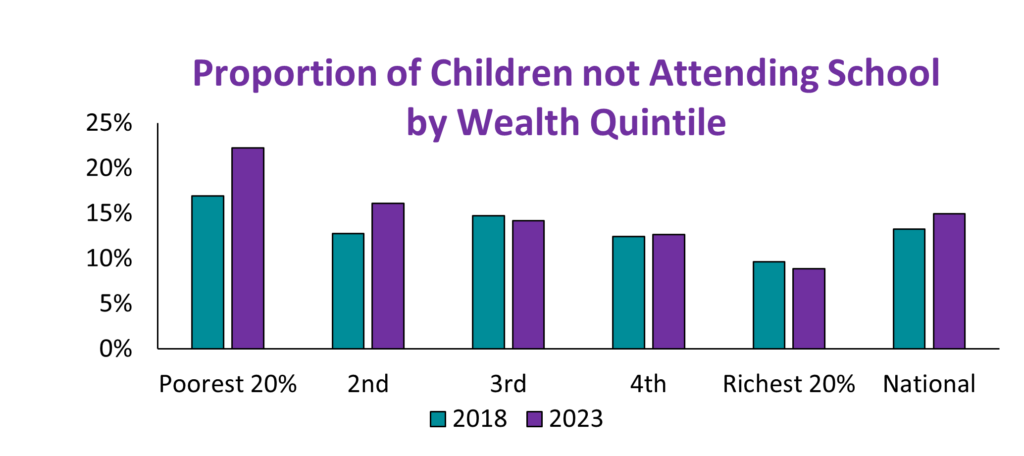

Second, there has been a rise in the overall proportion of children who do not attend school from 13% to 15%. This is due to falling rates of enrolment among households with below-average wealth.

Among the poorest 20% of households, the proportion of children not in school has risen from 17% to 22%; among the next poorest 20% of households, the proportion has risen from 13% to 16%. Among richer households, the proportion of children not in school has fallen slightly.

Pulling children out of school to work is one way in which parents can cope with lower income and a higher cost of living, and the number of poor households in this situation has increased over the last five years.

In this way, at least, the challenges of the last five years have affected poor households more than the relatively rich. This is likely to have lasting consequences for those children deprived of an education.

Food insecurity due to higher prices

Third, the rise in food prices in Bangladesh in 2023 has led to a substantial increase in the severity of food insecurity. 85% of households in the survey stated that recent high inflation had affected their spending.

Coping strategies included changing food habits (31%), drawing down savings (24%), reducing non-food expenditure (15%), and borrowing (12%). Between April and November 2023, the proportion of households reporting that they were coping by eating fewer types of food rose from 40% to 46%, and the proportion of households reporting that they were coping by eating less food rose from 20% to 24%; the proportion going without any food for a day or more rose from 1% to 2%.

Twin crises could have long-lasting consequences

Falling rates of school enrolment and higher rates of malnutrition are just two of the consequences of the twin crisis that are likely to have long-lasting effects on rates of poverty in Bangladesh.

Further analysis of the survey data is intended to reveal which types of households have been worst affected, which types of coping strategy have been most effective, and what policies might help households to rebuild their lives.

Feature Image Credit: Photo by Md. Akil Khan on Unsplash

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Please feel free to use this post under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Full information is available here.