A few months ago, the University of Manchester’s Post-Crash Economics Society and Rethinking Economics launched a report examining whether the economics curriculum is capable of tackling the world’s mounting crises. Global Development undergraduate and report contributor Sammi Dé wrote a blog about the report’s conception and his views surrounding the limitations of mainstream economic pedagogies.

Recently, Rethinking Economics published another scaled-up report examining the state of economics courses across UK universities. Now in his second year, Sammi reflects on some of the findings in the following blog, as well as the state of economics more generally.

On the 5th of November I had the opportunity to speak at Rethinking Economics’ (RE) national curriculum report launch, which took place at UCL. RE is somewhat of a parent organisation to the Post-Crash Economics Society, where I am Head of Campaigns. It is through their continued support that we were able to conduct our Manchester Curriculum Health Check last year, and have been able to sustain our campaign efforts. They describe themselves as a “global youth network working to make economics work for people, planet, and social justice”. The new report is essentially a scaled-up version of the health-check our society released last semester. It evaluates the economics courses of 20 universities across the UK by analysing module and course descriptions and grading them against a list of topics that we expect to be featured in an appropriate and relevant 21st-century economics education.

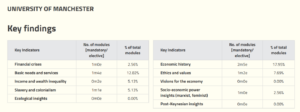

The University of Manchester has been ranked in the second-lowest category (escaping the lowest by 0.4 percentage points) and identified as ‘stuck in the past’. In contrast, SOAS and the University of Greenwich were the only curriculums evaluated as sufficient for the 21st century. These universities’ economics courses are considered pluralist and critical, incorporating significant discussions of issues of ecological sustainability, colonialism and inequality. I spoke with several students from these courses at the launch and heard their experiences of receiving a more progressive economics education. Our society is hoping to collaborate further with these universities’ RE groups, as we believe it is time for us at Manchester to take inspiration…

[Source: UK National Report: Is Economics Education Fit for the 21st Century? – Rethinking Economics]

The event began with an introduction given by Professor Ha-Joon Chang. A highlight from his speech was his observation that modern economics has become akin to Catholic theology in medieval Europe – dogmatic, providing the basis for how a large proportion of humanity sees/experiences the world, and a doctrine founded upon normative, ethical judgments that nonetheless claims universality.

This was followed by a presentation from Ross (from RE – and a key author in the report) who went over some key findings from the research. Some of the most notable are: 75% of universities do not teach any ecological economics; 55% do not provide meaningful teaching on slavery, colonialism or neocolonialism; 88.3% of theory modules purport mainstream neoclassical ideas; and economics, for the most part, is taught in isolation from other social sciences. These findings are alarming – the state of the undergraduate economics curriculum nationally is far from sufficient for training our future decision-makers.

Interestingly, insights from development studies are also largely omitted from curricula. Having experienced both a largely neoclassical economics education at A-levels, and then going on to study Global Development, I am aware of the power of narrative to transform an individual’s worldview. Our course’s focus on the Global South has made me more conscious of the spatial origins of economics’ current prevailing narratives and the structural barriers that exist to prevent any epistemological heterodoxy that may challenge the status-quo. I thus strongly believe in continuing to diffuse insights from development studies into mainstream economics, if we wish to fight the Eurocentrism and ahistoricism that currently dominates. (This being said, the relative merit of GDI’s approach does not exempt us from critical self-reflection. The origins of our discipline are inherently colonial and this continues to manifest today through the continued prevalence of rigid, top-down approaches to development theory and practice. We must recognise these roots, as well as the problematic historical role of our institution, and continue to fight colonial conceptions of the Global South as a space in darkness, and in need of “enlightenment”.)

I followed the report presentation with a speech that went into more detail about Manchester’s outdated course and Post-Crash’s efforts to change it. My last GDI blog went over this more thoroughly. Finally, there was an insightful panel discussion, featuring Yuan Yang MP (one of the founders of the RE movement) and Dr Carolina Alves. A highlight from this was when Carolina shared her critiques on the recent Nobel Prize for Economics. The winning paper from Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson is an extremely apt case of mainstream economics’ attempts to de-politicise and de-historicise processes of (under)development. It falls short in attempting to explain the formation of “good institutions” in the Global North through their commitment to being “inclusive” and “non-extractive”, omitting histories of colonial extraction, industrial policy, trade protectionism, and more. The Financial Times aptly faulted the paper for “econsplaining”, noting the authors’ tendency to take history out of context in order to justify a favoured conclusion. Given the presence of Yuan, the panel also discussed how changes to university curriculums and pedagogies can have direct impact on policy.

From this, I see it is crucial to maintain that economic pedagogy has the potential to transform lives. Our society’s campaign efforts are not some abstract, theoretical play. We believe that real change– climate justice, reduced inequalities, racial justice, ending hunger, etc.– will never occur so long as pedagogies remain dogmatic and outdated. A department like ours, then, that considers questions of global development, must continue to scrutinise any attempts made to universalise theory, and reject ideas that allude to an End of History. We are most certainly not out of History– this has become particularly apparent in light of Trump’s recent victory – so processes of unlearning must continue, in the fight for a better future.

I also had the opportunity to write a section of the preface of the national report, which I will include below:

A 21st-century economics education should allow students to cognitively place the discipline along an extensive historical timeline and identify the normative roots of all forms of economic thought. It should encourage students to challenge the dogmatic, hard-science-like mentalities of theories that no longer stand, opening the path for new, pluriversal models that better apply to our warming world. Global issues like climate change can only be tackled with complex, adaptable, and dynamic frameworks that account for a range of contexts.

Students and educators alike must therefore learn to recognise how pedagogy can often act as a tool used to reproduce existing power structures. Our curricula are dominated by Western knowledge systems, grounded in false assumptions regarding human nature, comparative advantage and the causes of inequality. Histories of colonisation, primitive accumulation and theorists from outside of the Global North are largely overlooked.

Recent atrocities in Gaza have provided a timely reminder of the ability of such pedagogies within economics to actively reproduce violent, colonial modes of operation- an idea equally applicable to the continued and disproportionate destruction brought about by climate change. In light of this, over the past year, we have questioned our universities’ claims of ‘academic neutrality’, whereby ‘neutrality’ appears to serve merely as a justification for sticking to the status quo.

A truly critical education should breed a generation of disobedient learners who are sufficiently equipped to challenge the status quo and think beyond the rigid pedagogies of the past. This should involve the unlearning of colonial logics, and transcending the positivistic illusions that attempt to take economics outside of history. For our planet, and the majority of its inhabitants, these efforts are not mere theoretical play, but a matter of survival.

by Sammi Dé, BSc Global Development/Post-Crash Economics Society, University of Manchester

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Please feel free to use this post under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Full information is available here.