Not the Fake News

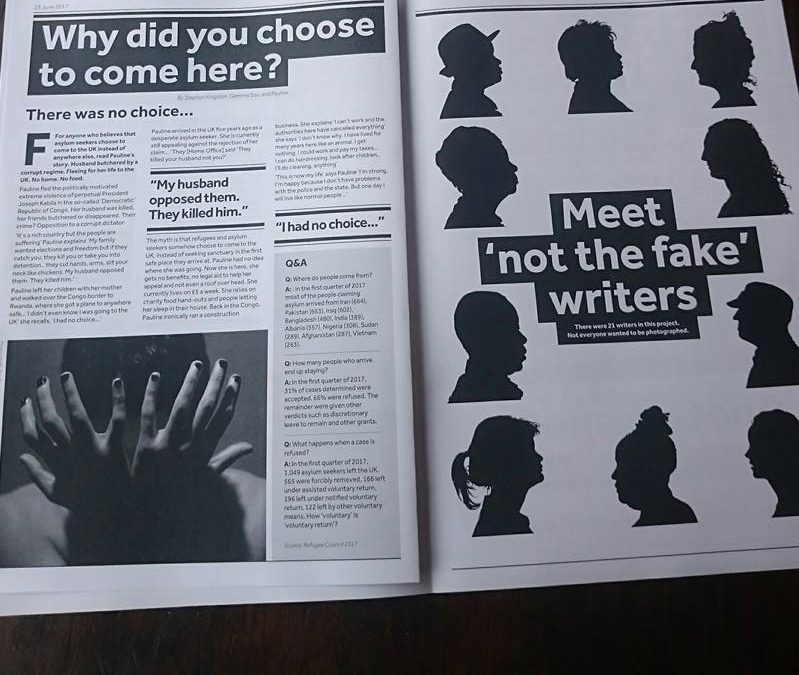

During refugee week, the Migration Lab hosted a newspaper writing workshop that produced ‘Not the Fake News about refuge and asylum. Written in one day by a group of displaced people in collaboration with Manchester-based journalists and migration researchers from The University of Manchester’s Migration Lab, this paper offers real stories of refuge and asylum by the people who have direct experience of these issues and those who research them. It has been delivered to various cafes, museums and libraries around the city and readers are encouraged to pass it on once they have read it. Copies have reached places as far flung as Lancaster and London. For more information and to download a copy, click here.

Stephen Kingston, one of the journalists involved in the project, has written the below article about the paper. It originally appeared in the Salford Star and has been re-blogged here. read more…

Not the Fake News

This blog originally appeared on the Manchester Migration Lab website.

During refugee week, the Migration Lab hosted a newspaper writing workshop that produced ‘Not the Fake News about refuge and asylum. Written in one day by a group of displaced people in collaboration with Manchester-based journalists and migration researchers from the University of Manchester’s Migration Lab, this paper offers real stories of refuge and asylum by the people who have direct experience of these issues and those who research them. It has been delivered to various cafes, museums and libraries around the city and readers are encouraged to pass it on once they have read it. Copies have reached places as far flung as Lancaster and London. read more…

What are the relationships between ageing, depression, non-communicable diseases and disabilities in South Africa?

By Manoj K. Pandey, Vani S. Kulkarni and Raghav Gaiha

Read the working paper: What are the relationships between ageing, depression, non-communicable diseases and disabilities in South Africa?

Old age is often characterised by poor health due to isolation, morbidities and disabilities in carrying out activities of daily living (DADLs), which lead to depression. Mental disorders – in different forms and intensities – affect most of the population in their lifetime. In most cases, people experiencing mild episodes of depression or anxiety deal with them without disrupting their productive activities. A substantial minority of the population, however, experiences more disabling conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder type I, severe recurrent depression, and severe personality disorders. Accordingly, a more nuanced and accurate picture of the mental health-related burden is crucial to effective allocation of resources and appropriately designed health systems in response to the nature and the scale of these challenges.

Motivated by these concerns, the latest GDI Working Paper “What are the relationships between ageing, depression, non-communicable diseases and disabilities in South Africa?” focuses on the determinants of depression among the over 60s in South Africa. Much of the recent literature offers an assessment of the influence of demographic, ethnic, living arrangements, marital status, morbidity, ADL limitations (or DADLs) but in a piecemeal and ad hoc manner using a specification that is neither comprehensive nor rigorous. In addition, several studies rely on a single cross-section or a single wave of the National Income Dynamics Study (SA-NIDS) which doesn’t allow incorporation of individual unobservable effects. Such effects are potentially significant as it is frequently observed that there is considerable variation in depressive symptoms even when old persons suffer from a common non-communicable disease and DADL.

Chronic and transient poverty in El Salvador: What are their determinants and how to better fight against poverty

By Werner Peña

Read Werner Peña’s working paper ‘What are the determinants of chronic and transient poverty in El Salvador?’

The situation of being in poverty can be experienced by households with different intensities over time: some can be trapped in poverty while others can move in or out from it from time to time. These differing experiences allow for the differentiation between chronic poverty and transient poverty. Chronic poverty means living in deprivation for long periods of time. On the other side, transient poverty means being vulnerable to risks that can cause households to fall into poverty. Thus, to better understand poverty, it is important to analyse the characteristics and determinants of these two faces of the same coin. To carry out this exercise, in a recent GDI Working Paper, I analysed the determinants of chronic and transient poverty in El Salvador.

The analysis was based on the construction of two un-intended panel data at household level using the main Salvadoran household survey, one for the period 2008-2009 and another for the period 2009-2010. The proposed determinants of chronic and transient poverty were grouped in five categories: demographic characteristics, access to economic resources, educational characteristics, labour characteristics and residence characteristics. The econometric techniques were the multinomial logit model and simultaneous quantile regression. read more…

Dr Saman Kelegama: scholar, policy influencer and caring human being

Professor David Hulme pays tribute to Dr Saman Kelegama

Professor David Hulme pays tribute to Dr Saman Kelegama

The sad news of Dr Saman Kelegama’s untimely death had shocked friends and academic collaborators across the world. At Manchester, as elsewhere, we feel the loss. Our condolences go out to all of his family and colleagues – we understand how deeply you will grieve.

Saman had been Sri Lanka’s leading economist and public policy analyst since the 1990s. He directed the Institute of Policy Studies in Colombo for many years until his death, applying his sharp intellect and well heeled diplomatic skills to ensure evidence and careful analysis informed debates about economic and social conditions across the country. He was a real scholar, thinking deeply about theory, methods, data and analysis, while feeding ‘useful knowledge’ into national policy debates at times that were often very politically charged.

The loss is not just for Sri Lanka – it is felt deeply across South Asia and amongst all who study the region. Saman was a leading member of the region’s economic associations and policy analysis networks, thinking carefully about the work of colleagues and constructively guiding them into more rigorous and accurate studies and developing regional perspectives.

Beyond his academic and policy work, Dr Saman Kelegama was a kind and caring human being. My professional image of Saman is of him presenting excellent papers at scholarly meetings. My personal memory of Saman will be of cups of tea in the garden of the Galle Face Hotel in the 1990s, gently mulling over ideas about the ways in which human progress might be achieved across the world.

Read further reflections from the Institute for Policy Studies staff.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Taxi to Tel Aviv: Precarious lives, contested freedoms – laying claim to asylum in cities of the Global North

This blog originally appeared on the Manchester Migration Lab website

By Dr Tanja R. Müller

This post originally appeared on Tanja R. Müller’s blog Aspiration and Revolution

In Germany, it is pre-election time. And the leader of the main opposition party, Social Democratic (SPD) candidate Martin Schulz, has finally found what he believes to be the most potent weapon to dent the popularity of incumbent Chancellor Angela Merkel: Lashing out at her policy towards refugees and migrants.

African business owner argues with hostile protesters in Tel Aviv. photo: Stefan Boness, http://www.iponphoto.com

We could very soon, Schulz claims, be in a similar situation again as in the summer of 2015. Then, refugees and migrants were stranded at the borders of various countries in mainly eastern Europe, and Chancellor Merkel – in an act most then regarded as gracious and compassionate, others as stupid and naïve – decided to do what was needed and morally right (if one believes in a common humanity): welcoming them to Germany under the slogan wir schaffen das (we will manage).

And indeed, Germany has managed by and large, in spite of some initial chaos, and the fact that processing and social welfare institutions were overwhelmed at times, in spite of the fact that a newish right wing party gained votes in various local and state elections. For every act of resentment, one could observe manningfold acts of welcome and compassion. Many of those who arrived in 2015 have settled, found work, their children go to school. Others are living somewhere below the official radar, often in Germany’s bigger cities, get by in different ways in their attempts to rebuild lives –while others have been sent back to countries deemed safe enough to return to, a decision that is always contentious, as what does ‘safe enough’ really mean in practice?

Now, Schulz claims, a situation comparable to 2015 could arise again soon, as more and more refugees and migrants arrive in Italy again. EU mechanisms to share that ‘burden’ are not working, as in particular countries in Eastern Europe refuse to participate, and Italy itself is feeling left alone and overwhelmed. Its reception centres are full – even as many of their inhabitants have made their way to Rome or other urban settings given the chance, living an often precarious life but also happy to have made it, in contrast to so many others who have perished on their journeys.

These recurring dynamics in the countries of Southern Europe in particular, those with a shoreline facing the African continent, had a precedent in a perhaps unlikely country, Israel. Here many of the dynamcis later to be observed in Europe were played out in quasi laboratory circumstances from around 2005 onwards: Israel then experienced its first and unprecedented movement of non-Jewish refugees – mainly from Eritrea and Sudan. Those refugees had previously resided in Egypt and Libya, and wider political circumstances made both countries unsafe to continue to stay there. Israel was perceived by those who then came to it as ‘the Europe we can walk to’ – and Israeli authorities were in many ways as unprepared as most European countries were in the course of 2015, when movements of refugees and migrants perceived as unprecedented arrives at their shores. Thus Israel provides a good example to explore in a quasi-laboratory setting the range of responses along the whole scale we subsequently saw in Europe, from alienation to solidarity – and their limitations.

Initially, the first refugees who arrived, while described as ‘infiltrators’ in official discourse, were at the same time regarded as useful additions to the labour force, replacing former Palestinian workers in the course of the second Palestinian intifada. But with increasing numbers and increasingly hostile political propaganda, the official Israeli response become harsher nad harsher over time. A quasi-dentation facility was built in the Negev desert to which some of those who previously lived more or less unhindered in Tel Aviv and other cities were forced to report and stay, financial ‘incentives’ (often accompanied by threats) were given to some to leave for a third country often with serious consequences for their safety and well-being, and of late those who still work and have built new lives in Israeli cities have been hit by a new withholding tax (to be paid only once they have left the country).

But that is only one side of the story – bureaucratic hurdles, prohibitive laws, be it in Israel, Europe or other settings in the Global North who in any case only receive a small slice of those seeking refuge and asylum globally. Many of the modern day sans papiers – whether they have actually lodged an official asylum application that might one day be decided positively or not, find ways to live meaningful lives in the cities where they have been stranded by accident or arrived by planning. A taxi to Tel Aviv can mean hardship or the fulfilment of a dream, the beginning of a journey and an experience of freedom many might not have enjoyed for a long time – even if overall their lives often remain in a state of limbo. Yes, hostile receptions, sometimes outright hostility and a culture of un-welcoming are part of the bigger picture – and were so equally in Germany behind some of the refugees-welcome banners of the summer of 2015. But so are warm welcomes, contestations of hostility and speaking out with and on behalf of the stranger. Contestations create a space, however small, for conviviality and a solidaristic way of being with others.

Refugees were welcome in Germany in 2015 – not by all but by enough to make a difference, and they were equally welcome in Tel Aviv and Rome and multiple other cities – not by all, but by some, and each welcome can make a great difference for the individual at least, if not always the wider political scene.

Large population groups in many of our cities may lack formal rights – but they still manage to occupy a political space where they live some of the rights they formally lack in daily encounters – even if often life may feel like a daily struggle. Some of those struggles in Tel Aviv are being told in my latest publication – and I hope will remind the reader of the role we can all play in making our cities – bit by bit and in small steps – more convivial.

The publication is question is Tanja R. Müller, 2017. Realising rights within the Israeli asylum regime: a case study among Eritrean refugees in Tel Aviv, African Geographical Review, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2017.1354309

UK political parties are shifting from ‘international’ to ‘global’ development

By Dr Eleni Sifaki, Research Associate, Global Development Institute

The geography of global development in the 21st century is shifting. Horner and Hulme call for a shift in academic development studies and development policy from ‘international development’ to ‘global development’ to address emerging global inequalities that transform dichotomies between developed and developing world.

Today the world is faced with global development challenges that transcend North/South divisions such as climate change and the refugee crisis. The 2015 SDGs reflect this change in understanding of development, as they are universal, applying to all countries irrespective of their development status.

In light of this shift in the geography and consequently the understanding of development, I have been working with David Hulme to examine the extent to which political parties in the UK have a) shifted from ‘international’ development to a recognition of ‘global’ development in response to economic, environmental and social challenges, and b) the extent of their commitment to global development. read more…

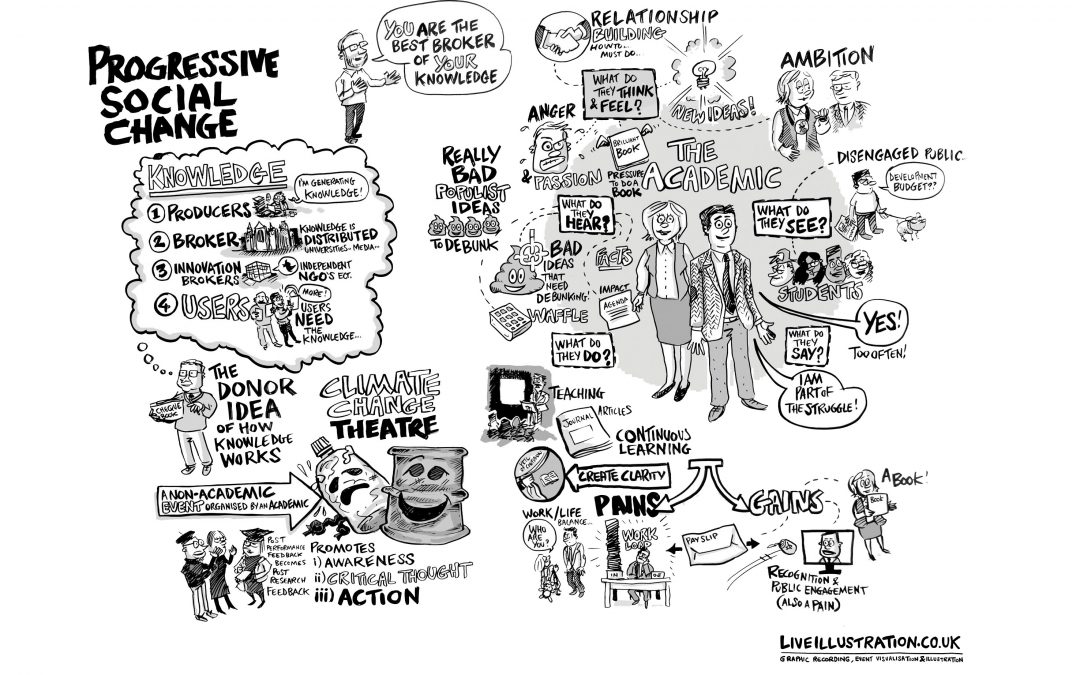

How can development academics help change the world?

Chris Jordan, Communications and Impact Manager, Global Development Institute

For most development-focused academics, the main reason they join the profession is to contribute towards positive social change. Contrary to the increasingly outdated image of out of touch academics, IDS’s James Georgalakis recently observed, “hard as I look, I can’t see any ivory towers – only scientists desperately worried about fake news, academic freedoms and results-based research agendas.”

Traditionally, many joined Development Studies departments following years of practice in NGOs and international organisations, seeking the space to inform or challenge the broader intellectual frameworks that guide development, rather than working on individual projects. The academics I work with at the Global Development Institute are incredibly well networked, attuned to the big issues on the horizon and motivated to do something about them.

But despite the practical orientation of development studies and the intrinsic drive of most academics working within the discipline, it’s not always clear exactly how academics with particular specialisms, at different stages of their career, can most effectively contribute to changing the world for the better.

Academics in the UK are now working in a context in which ‘Impact’ is demanded more and more by donors and assessment agencies. There are clear benefits to this agenda, which helps to raise the status of engaged, problem-solving research and can provide the resources researchers need to ensure their ideas gain traction beyond academia. But there’s also a risk that the impact agenda ends up instrumentalising research, possibly squeezing out the potential for more conceptual and theoretical work. read more…

A Climate Resilient Approach to Social Protection

Dr Joanne C. Jordan, Global Development Institute, University of Manchester, UK

Climate change is one of the biggest environmental and development challenges of the 21st century. But we will not all face this challenge in the same way, as the impacts of climate change are unevenly distributed; people that are marginalised in society are especially vulnerable to climate change because of intersecting social processes that create multidimensional inequalities.

Climate change and the inequalities in its impact are a key challenge for social protection programmes aimed at combating extreme poverty in the Global South. Climate change is likely to intensify the types of risks that those enrolled in social protection programmes will experience in the future.

However, there are few projects that integrate both climate change resilience and social protection objectives, despite both aiming to reduce the risks experienced by vulnerable people. Later this year I will carry out research examining what the ‘Infrastructure for Climate Resilient Growth in India’s (ICRG) experience can tell us about the effects of building a climate resilient social protection approach in Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Scheme (MGNREGS) and other public works programmes.

Listen: Sally Cawood discusses domestic violence in Bangladesh

Sally Cawood, PhD researcher at the Global Development Institute discusses domestic violence in the slums of Bangladesh in our latest podcast.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.