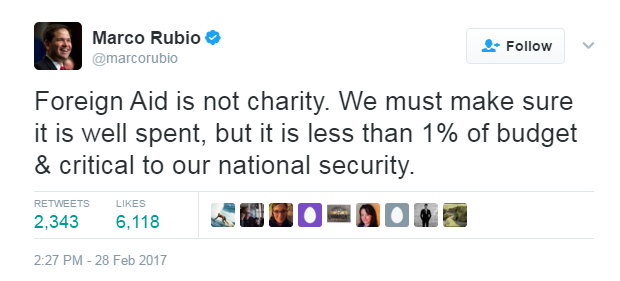

Why are right wing Republicans standing up for international aid?

By Professor David Hulme, Executive Director Global Development Institute

The Trump administration looks set to propose “fairly dramatic reductions” to America’s aid programme later this month. This is unsurprising given the extreme nationalism of his “America First” approach, but why are Republican senators like Marco Rubio speaking out?

ODI’s Alex Thier has some interesting thoughts about why many US senators and congressmen will oppose cuts, arguing that ultimately they will make America weaker in the world. read more…

Transforming the role of women in Global Value Chains #IWD2017

This International Women’s Day 2017 the campaign theme is #BeBoldForChange – a call for us to forge a better, gender inclusive working world.

The Global Development Institute’s Professor Stephanie Barrientos has been researching the sustainability of global value chains including cocoa, fresh vegetables, fruit, flowers and garments for over 15 years. Her research played a positive role in addressing global inequalities and supporting initiatives to empower women workers. Some of her recommendations were used as the basis for the Cadbury Cocoa Partnership which later evolved into today’s Cocoa Life scheme.

So why are we looking at Stephanie’s work on International Women’s Day 2017?

We are seeing increasingly large numbers of women drawn into employment in global value chains – compared to more traditional forms of production. It is estimated 70% of world trade now passes through value chains, many led by global retailers. Stephanie’s research highlights the challenges and benefits to women of working in global value chains:

- Women constitute a significant share of the workforce in labour intensive production in global value chains, but are concentrated in precarious and flexible work with poor labour conditions

- At lower value chain tiers many workers’s incomes are below a living wage. Women workers often experience verbal and sexual harassment from male supervisors.

- Downward pressure on costs and increased requirements for flexibility placed on suppliers reinforces precarious working practices.

Quality standards required by buyers can raise demand for more skilled workers, which helps drive improvements in working conditions and rights

Research has shown paid work in global value chains increases women’s economic independence and voice. However, proactive strategies are needed to promote greater gender equality and women’s economic empowerment.

Recently Stephanie gave presentations at SOAS University of London and University of Warwick on ‘Retail Shift: Transforming Work and Gender in Global Value Chains’. She advanced a gendered analysis of global (re)production networks (GrPNs), drawing on global value chain analysis, labour geographies and feminist political economy.

Drawing on case studies on women’s work in cocoa, fruit, flowers and garments, her research shows outcomes for women can be mixed. Those caught in ‘low road’ cheap labour value chains experience poor conditions and low wages. Those engaged in ‘high road’ value chains requiring greater skill and productivity are more likely to enjoy better conditions and rights.

Stephanie’s research provides insights into social upgrading and downgrading (better or worse conditions and rights), and how these play out for different workers. It examines to what extent engaging in global value chains reinforces gender inequalities or opens up channels for promoting gender equality and women’s economic empowerment.

Social upgrading for women workers can occur under some circumstances, but it is far from automatic:

- Civil society campaigns can help to leverage improvements in working conditions and gender equality. This occurred in the Kenyan flower industry over the past decade.

- Company moves to increase quality and productivity, and rising concerns over the future resilience of their supply chains can help drive improvements. This is now occurring in cocoa-chocolate value chains following industry predictions of a million ton cocoa shortage by 2020.

- Government regulation needs to be more proactive in ensuring better labour conditions and rights for all workers (permanent and casual). This must include ensuring workers earn a living wage and smallholder farmers a living income.

In conclusion Stephanie argues that changing retail procurement practices and changing patterns of consumption in developed and emerging economies are transforming gendered patterns of work. Downward pressure on costs, quality standards, civil society campaigns and increased requirements for skilled labour are resulting in complex gender dynamics.

Effective governance and proactive strategies by all actors (public, private and social), is critical to promoting greater gender equality in global retail value chains and supporting women’s economic empowerment.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

The race for Sustainable Development by 2030: Some baby-steps towards leaving no one behind

By Fortunate Machingura, a Global Challenges Research Fund Postdoctoral Fellow at the Global Development Institute, University of Manchester. Fortunate holds a PhD in Development Policy and Management from the University of Manchester

By Fortunate Machingura, a Global Challenges Research Fund Postdoctoral Fellow at the Global Development Institute, University of Manchester. Fortunate holds a PhD in Development Policy and Management from the University of Manchester

The aphorism that the populations furthest behind should be reached and no one should be left behind continues to consume the development world. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have galvanised thinking about how to leave no-one behind, based on optimism around the world’s ability to cooperate and govern for sustainability towards ending poverty, deprivation, and inequality for all. Questions of who these populations are, where they live and what kinds of inequalities they experience are critical.

Some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have taken the leave no-one behind mantra to heart; policymakers, NGOs, the private sector, donors and other decision-making stakeholders, are making frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment of populations and social groups that are “behind”. For example:

- South Africa’s National Development Plan (NDP) 2030 speaks to the SDGs and aims to eliminate poverty, create jobs and reduce inequality for all, by 2030.

- In Ghana, the SDGs form an integral part of its 2014-2017 national development plan (Shared Growth and Development Agenda) demonstrating initial steps towards localising the SDGs.

- Zimbabwe has assigned each of the 17 SDGs into (sub)clusters of the current National Development Plan (Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Socio-Economic Transformation 2013-2018) ahead of the next Development plan post-2018.

At the project and program level, improved methods and more rigorous approaches to evaluation of development outcomes have led to a massive effort to ensure that resources are mobilised and effort is deployed to the best effect for poorer quintiles of the population who need these resources the most. read more…

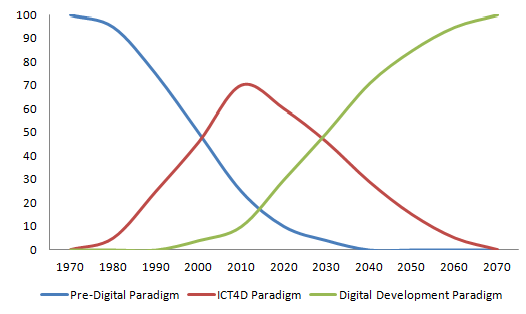

An Emerging Digital Development Paradigm?

Taking a longer-term view, the relationship between digital ICTs and international development can be divided into three paradigms – “pre-digital”, “ICT4D”, and “digital development” – that rise and fall over time (see Figure below).

The pre-digital paradigm dominated from the mid-1940s to mid-1990s, and conceptualised a separation between digital ICTs and development [1]. During this period, digital ICTs were increasingly available but they were initially ignored by the development mainstream. When, later, digital technologies began to diffuse into developing countries, they were still isolated from the development mainstream. ICTs were used to support the internal processes of large public and private organisations, or to create elite IT sector jobs in a few countries. But they did not touch the lives of the great majority of those living in the global South.

The ICT4D paradigm has emerged since the mid-1990s, and conceptualised digital ICTs as a useful tool for development [2]. The paradigm arose because of the rough synchrony between general availability of the Internet – a tool in search of purposes, and the Millennium Development Goals – a purpose in search of tools. ICTs were initially idolised as the tool for delivery of development but later began to be integrated more into development plans and projects as a tool for delivery of development.

The isolationism of the pre-digital paradigm remains present: we still find policy content and policy structures that segregate ICTs. But integrationism is progressing, mainstreaming ICTs as a tool to achieve the various development goals. From the development side, we see this expressed in national policy portfolios, in Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers, in UN Development Assistance Frameworks. From the ICT side, we see this expressed in national ICT policies and World Summit on the Information Society action lines.

The ICT4D paradigm is currently dominant and will be for some years to come. Yet just at the moment when it is starting to be widely adopted within national and international development systems, a new form is hoving into view: a digital development paradigm which conceptualises ICT not as one tool among many that enables particular aspects of development, but as the platform that increasingly mediates development.

This is the subject of a Development Informatics working paper: “Examining “Digital Development”: The Shape of Things to Come?”, and will be the topic for future blog entries.

[1] Heeks, R. (2009) The ICT4D 2.0 Manifesto: Where Next for ICTs and International Development?, Development Informatics Working Paper no.42, IDPM, University of Manchester, UK

[2] ibid.

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

How can we amplify the leadership of southern climate scientists?

By Professor David Hulme, Executive Director of the Global Development Institute

I recently had the privilege of delivering a lecture at the IUB University and ICCCAD in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Much of the presentation was based on the recent book Bangladesh Confronts Climate Change by Roy, Hanlon and Hulme.

The lecture, and discussions over dinner with GDI alumni afterwards, felt a lot like ‘bringing coals to Newcastle’ as the book lauds the leadership that Bangladeshi scientists have provided to knowledge production and in taking their evidence to policy with Ainun Nishat, Saleemul Huq and other scientists attending. read more…

Uma Kothari: The power of a warm welcome: Forging a humanitarian response to refugees amid negative media imagery

Professor Uma Kothari, from the Global Development Institute, recently appeared on The University of Melborne’s online, audio talk show of research, opinion and analysis, Up Close. She discussed how media representations of asylum seekers influence us in how we attend and respond to the plight of individuals and groups fleeing their countries in search of safety. You can listen to the discussion in full below. read more…

GDI Lecture Series: Predatory states and Economic development with Professor Mehrdad Vahabi

On Wednesday, 22 February, Professor Mehrdad Vahabi gave a lecture entitled ‘Predatory states and Economic development ’. You can listen to the lecture in full or watch the live stream below

Divergence, big time to converging divergence: From international to global development?

In a new paper, published in the GDI Working Paper series, Rory Horner and David Hulme argue that the macro-scale map of development has shifted from “divergence, big time” to “converging divergence”, which consequently requires a shift from thinking of international development to global development.

The contemporary global map of development appears increasingly incompatible with any notion of a clear spatial demarcation between First and Third Worlds, “developed” and “developing”, or rich and poor, countries. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), agreed in 2015, have a global focus that represents a universalisation of the challenge of development, a clear departure from the Millennium Development Goals’ (MDGs) almost exclusive focus on developing countries. The World Bank declared in April 2016 that it will no longer distinguish between developed and developing countries in its annual World Development Indicators. Although increasingly widespread recognition exists that the distinction between “developed” and “developing” countries is no longer tenable, enormous inequality and unevenness persists, and to some extent is even augmented, under a new spatial configuration of development. What then is the new “map” of development?

The “old” focus of international development was based on addressing what Lant Pritchett referred to as “divergence, big time” – the major departure in terms of economic development between developed and developing countries across the 19th and 20th centuries. “Poor people” were assumed to be synchronous with “poor places”. Various critical scholars questioned this binary, yet it remained dominant. The developed/developing country divide persisted through the second half of the 20th century to such an extent that the MDGS, the major development framing exercise of the late 20th century, were almost completely set within this type of macro-geographical categorisation: they were a rich world product which set targets for poor countries. read more…

Inequality: policy bandwagon or a welcome shift?

The Global Development Institute recently held a workshop examining global inequalities, which brought together four of the Institute’s leading academics to grapple with various aspects of the ‘issue of the moment’. Two central questions were up for discussion:

- Why is inequality important as a conceptual and normative framework?

- Is the current interest in inequality in development a policy bandwagon or a welcome shift?

Prof Armando Barrientos began by remembering Sir Tony Atkinson and Derek Parfit, dearly missed colleagues who passed away in January, and both of whom contributed enormously to the academic landscape on inequality. Prof Barrientos noted that inequality is actually declining in low and middle income countries – and there is a need to look more closely at why that may be. He also pointed out that there is a tendency to assume that whoever demands inequality is in fact egalitarian. Prioritarianism may be the smarter way to go: the worse off people are, the more benefits they should receive. Yet, how those benefits might be delivered is unclear: proponents of global inequality reduction aren’t entirely sure how to achieve it. The best way we currently have through policy is through fiscal policy, specifically transfer systems. Nordic countries excel at this thanks to their progressive systems of transfer and taxation, but these (and personal income taxes in particular) do not exist in developing countries. Low and middle income countries, such as those in Latin America, that have managed to reduce inequality have not done so by altering the taxation system, but by reforming the expenditure system. So one solution may be to say: let’s not bother so much with how we collect taxes, and instead concern ourselves with how we spend it, and let’s spend it very progressively. read more…

Prof Armando Barrientos began by remembering Sir Tony Atkinson and Derek Parfit, dearly missed colleagues who passed away in January, and both of whom contributed enormously to the academic landscape on inequality. Prof Barrientos noted that inequality is actually declining in low and middle income countries – and there is a need to look more closely at why that may be. He also pointed out that there is a tendency to assume that whoever demands inequality is in fact egalitarian. Prioritarianism may be the smarter way to go: the worse off people are, the more benefits they should receive. Yet, how those benefits might be delivered is unclear: proponents of global inequality reduction aren’t entirely sure how to achieve it. The best way we currently have through policy is through fiscal policy, specifically transfer systems. Nordic countries excel at this thanks to their progressive systems of transfer and taxation, but these (and personal income taxes in particular) do not exist in developing countries. Low and middle income countries, such as those in Latin America, that have managed to reduce inequality have not done so by altering the taxation system, but by reforming the expenditure system. So one solution may be to say: let’s not bother so much with how we collect taxes, and instead concern ourselves with how we spend it, and let’s spend it very progressively. read more…

The first year of the Global Development Institute