How the poor borrow

By Stuart Rutherford, Honorary Research Fellow at The Global Development Institute

This is the third in a series of short articles about the findings of a daily ‘financial diary’ research project. A description of the project can be found at its web-site. Details of the poverty levels of our 50 ‘diarists’ can be found in the article on savings listed on the publications page there. In short, they fall into four classes, ranging from extreme poor to near-poor. In this article, we look at the borrowings of our diarists, using daily data for the period from March to October 2016.

A minority of non-borrowers

We have complete daily transaction records for 49 diarist households for that 8-month period, during which 43 of them borrowed, made repayments on borrowings, or (mostly) did both. That leaves six who did not borrow nor repay – so who are they? Our Table shows they are a mixed bunch, not restricted to any specific income level, occupation, or household size. They all save. read more…

Screening of The Divide documentary sparks public conversation on inequalities

In the wake of Donald Trump’s election and on Equal Pay Day, the Global Development Institute was proud to hold a free, public screening of The Divide at The John Rylands Library.

In the wake of Donald Trump’s election and on Equal Pay Day, the Global Development Institute was proud to hold a free, public screening of The Divide at The John Rylands Library.

Around 60 members of the public attended the event in the Historic Reading Room and saw the film which was screened as part of the week long ESRC Festival of Social Sciences. The screening was also an example of our commitment to public engagement around addressing global inequalities – one of our five research beacons of excellence at The University.

The Divide film is inspired by the critically-acclaimed, best-selling book “The Spirit Level” by Professors Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett. It charts the story of seven individuals striving for a better life in the modern day US and UK where the top 0.1% owns as much wealth as the bottom 90%. By plotting these tales together, the film uncovers how virtually every aspect of our lives is controlled by one factor: the size of the gap between rich and poor. read more…

GDI Lecture Series: Capitalism and Conservation in the Age of Security with Professor Libby Lunstrum

On Wednesday, 9th November Professor Libby Lunstrum from York University in Canada discussed Capitalism and Conservation in the Age of Security: The Vitalization of the State You can find the video and podcast from the event below.

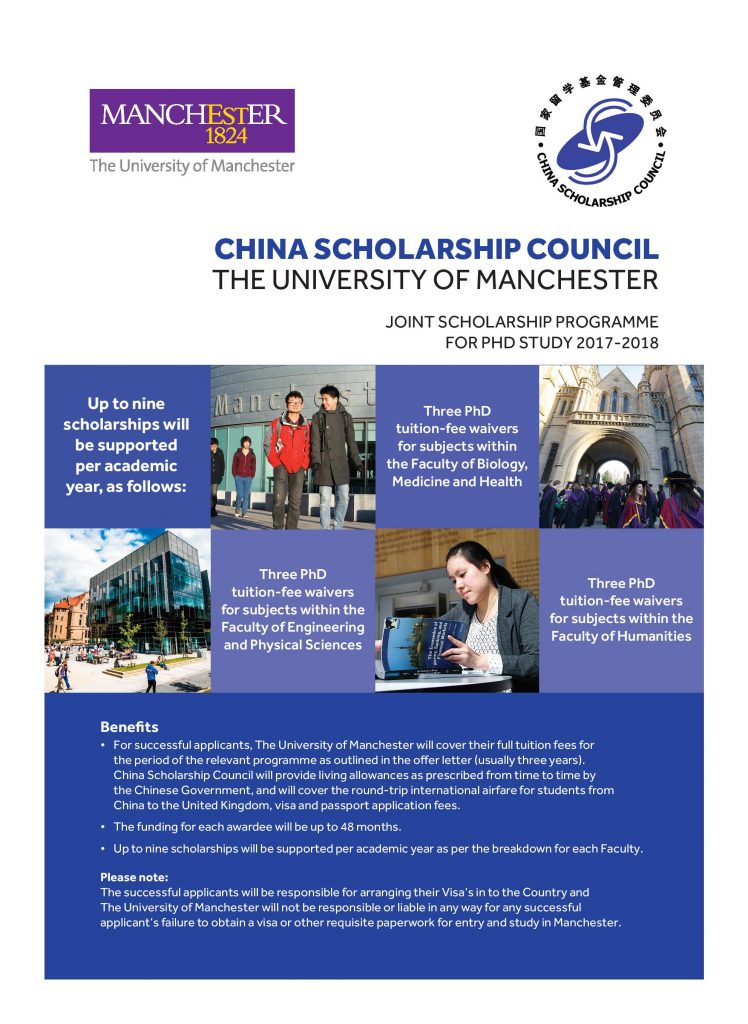

China Scholarship Council (CSC) – University of Manchester Joint PhD Scholarships 2017-18

Watch | Bina Agarwal at the New School for Social Research

On Tuesday, 25 October Bina Agarwal gave a lecture at the New School for Social Research in New York.

Her lecture demonstrated how women face deep inequalities in rules, norms, and social perceptions, which, in turn, create severe inequalities in their access to both private and public property. Based on her research, she challenged standard economic analysis to show how these inequalities undermine both economic efficiency and social justice. She also outlined pathways for change, such as enhancing women’s bargaining power in multiple arenas: the family, community, markets, and state. read more…

Brazil in political crisis: what has happened, and what might it mean for development?

IRIBA’s research has argued that in recent decades Brazil has followed a distinctive development trajectory. This has centred on inclusive growth and the use of innovative tax-financed social policy in reducing poverty and inequality and bolstering long term human development. However, current events are rather more bumpy, including a bona fide political crisis of dizzying proportions. What is going on and what might be the implications for development? I’ll take those in turn. Firstly, a not-entirely-impartial synopsis:

What is happening politically?

President Dilma Rousseff, of the centre-left Workers’ Party (PT) was impeached in a vote by Congress, and her administration supplanted by one headed by the centre-right Michel Temer (PMDB). Dilma was culpable forwindow-dressing government accounts to make public spending appear lower. This followed huge demonstrations mobilised under an ‘anti-corruption’ motif. So, a victory for people-power holding corrupt politicians to account, right? read more…

The Global Development Institute is Hiring

What do poor households spend their money on?

By Stuart Rutherford, Honorary Research Fellow at The Global Development Institute

The ongoing Hrishipara Daily Diary project records the daily money flows of 50 low-income households living near a market town in central Bangladesh. More details about the project, and about the relative poverty levels of the ‘diarists’ are given in another blog. 22 of the diarists – we call them the ‘extreme poor’ and the ‘very poor’ – have incomes below the ‘$2 a day per person PPP’ level. The 28 with higher incomes we categorise as ‘moderate poor’ and ‘near poor’.

The composition of total outflows

Our data collection records all the money that flows in and out of the diarists’ hands. We begin with a chart that shows the main categories of the total outflow. read more…

GDI Lecture Series: The UK’s Post-Brexit Trade Deal with Professor Alan Winters

On Wednesday, 26th October Professor Alan Winters discussed the UK’s Post-Brexit Trade Deal. Professor Winters is a Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex and former Chief Economist at the Department for International Development. You can find the slideshare, video and podcast from the event below. read more…

Rising Powers at the DSA 2016: China and the rising powers as development actors

By Corinna Braun-Munzinger, PhD researcher at the Global Development Institute

The Rising Powers Study Group of the Development Studies Association (DSA) and the ESRC Rising Powers and Interdependent Futures programme jointly convened a full-day panel at the DSA annual conference in Oxford on 13 September, titled “China and the rising powers as development actors: looking across, looking back, looking forward”. These issues were approached from various angles – ranging from a macro perspective on fundamental shifts in the global world order to the micro-level perceptions of individual development workers in South-South cooperation.

The Rising Powers Study Group of the Development Studies Association (DSA) and the ESRC Rising Powers and Interdependent Futures programme jointly convened a full-day panel at the DSA annual conference in Oxford on 13 September, titled “China and the rising powers as development actors: looking across, looking back, looking forward”. These issues were approached from various angles – ranging from a macro perspective on fundamental shifts in the global world order to the micro-level perceptions of individual development workers in South-South cooperation.

The discussions began from a broad perspective on how the rising powers influence development prospects globally. Rory Horner, University of Manchester, started out by tracing how the traditional distinction between developed and developing countries has become blurred as a result of the emergence of the rising powers, calling for more research on a beginning new era of more universal, global development. Albert Sanghoon Park, University of Cambridge, complemented this forward-looking perspective by taking a look back at the historical geopolitical patterns underlying the developed-developing country dichotomy since the 1940s. Seen from this angle, possible tensions between the ideals and the geopolitics of development are neither new, nor are they likely to disappear with the rising powers taking on stronger roles in shaping global development. Following from these broader thoughts, Anna Wrobel, University of Warsaw focused on trade policy as one specific aspect in which China engages in shaping the global economic order, both through the WTO and through bilateral agreements.