Richard Heeks, Professor of Development Informatics, Global Development Institute

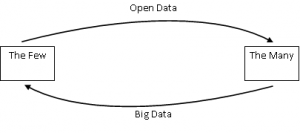

At a recent CDI brown-bag discussion on data-intensive development, we hypothesised a mirror-image power dynamic between big data and open data.

Open data has an inherent tendency to redistribute power from the few (who originally hold the data) to the many (who can now access the data). It supports sousveillance. Big data has an inherent tendency in the opposite direction. It gathers data about the many but only the few have the power to capture, store, process, interpret and use that big data. It supports surveillance.

The extent to which these are inherent affordances of these data systems vs. the extent to which these tendencies are inscribed into those data systems is a matter for further debate. But what it does suggest is that big data per se is more reproductive than transformative of power inequalities within society. Think of the way in which major users of big data – social media platforms, e-business multinationals, telecommunication companies – operate. Their uses of big data reinforce inequality much more than they challenge it.

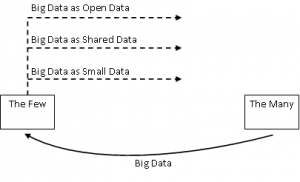

One way to address this is to reverse the power dynamic flow shown above: big data must become open data. This could happen in various ways:

- Big data as open data: big datasets are made openly available online in accessible format (as in all cases, with due consideration for data privacy and security).

- Big data as shared data: big datasets are made available to particular organisations (e.g. those of civil society).

- Big data as small data: sub-sets of big datasets are shared with the sources of that data for their use (e.g. the particular communities or groups from which the big data derived).

But what will make a reversal happen? To understand this, we need to study open data motivations: what causes organisations to open their datasets? Reviewing our knowledge of open data, we could not find examples of intrinsic motivations driving adoption of open data. Instead, drivers to opening of big datasets seem likely to be extrinsic:

- For public sector owners of big data, domestic political economy (e.g. local campaigns for access to data; economic benefits from creation of a local data economy) and external political economy (e.g. encouraging foreign investment through a reputation for openness).

- For private sector owners of big data, government regulation to force opening of datasets, or shareholder/consumer pressure.

Without such extrinsic pressures and the openness that ensues, big data may not deliver its developmental potential.