Save our chocolate!

Judith Krauss is a post-doctoral associate at the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Doctoral College and researched cocoa sustainability for her PhD thesis.

Can I ask you a question? Do you like chocolate? If your answer is ‘yes’, as for 100% of my focus-group and public-engagement participants, you may be interested to know that the people manufacturing your favourite treats are not entirely sure where your fix’s key ingredient will come from four years from now.

Can I ask you a question? Do you like chocolate? If your answer is ‘yes’, as for 100% of my focus-group and public-engagement participants, you may be interested to know that the people manufacturing your favourite treats are not entirely sure where your fix’s key ingredient will come from four years from now.

Six years ago, projections that cocoa demand would outstrip supply by about 25% by 2020 began circulating. Factors contributing to the shortage concerns include: cocoa cultivation’s lacking attractiveness for younger generations given decades of low prices, productivity-maximising practices degrading limited production surfaces and the unknown variable of climate change, as well as only a handful of companies controlling the marketplace. The impending doom has prompted the chocolate sector to begin engaging with ‘cocoa sustainability’ to address these issues and safeguard its key ingredient’s long-term availability.

The bad news: nobody quite knows how to do that.

The good news: chocolate-industry actors have begun engaging in various fora and initiatives to address a problem together which is too monumental for any one stakeholder to tackle alone. One such forum, bringing together diverse chocolate-industry actors from civil society, public sector and private sector, is the World Cocoa Conference (WCC), taking place in the Dominican Republic from 22 to 25 May 2016. Stakeholders from all facets of the cocoa sector have congregated to discuss ‘Building bridges between producers and consumers’, with a view to ‘connecting the whole of the value chain’.

My PhD research sought to do just that, using a global production networks lens to incorporate voices from cocoa producers via companies, public sector and NGOs to chocolate consumers. Through in-depth interviews and participant observation in Latin America, I aimed to find out what cocoa producers, cooperatives and NGOs make of ‘cocoa sustainability’. Back in Europe, I sought to establish companies’, public-sector representatives’ and consumers’ take on the omnipresent term. In keeping with the WCC’s theme of building South-North bridges, I fed back through interviews, focus groups and public engagement what I had learned especially from Nicaraguan stakeholders.

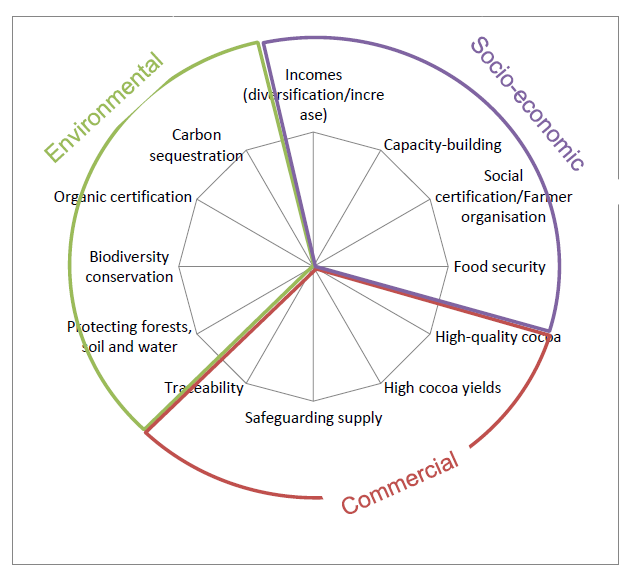

Regarding the ‘cocoa sustainability’ challenge, my research produced some more good news and some more bad news. The bad news first: a key difficulty with the concept of ‘cocoa sustainability’ is that various actors bring different understandings of what it is or is to entail to the table. This polysemy on the one hand works in the concept’s favour, as its aspirational quality renders it a notion which diverse stakeholders happily agree on. However, it also paints over different framings of what ‘sustainability’ is to entail: some prioritise its potential to improve grower livelihoods through better prices and cultivation conditions, others emphasise its links to global environmental challenges; a third dimension concerns predominantly commercial concerns such as supply security, i.e. the business imperative which ‘sustainability’ has become in the sector.

The good news is, however, that because of cocoa stakeholders’ puzzlement at how to bring about ‘cocoa sustainability’, they are willing to rethink time-honoured processes and procedures. I believe this awareness is an opportunity to create genuine, fair partnerships between stakeholders throughout the supply chain. One avenue to get closer to some equitable conversations, I believe, could be the ‘constellations of priorities’ model which I developed in my work, a tool to (self-)assess stakeholder priorities so that all actors within an initiative can identify where their socio-economic, environmental and commercial drivers overlap, dovetail or collide.

My hope is that the model can help practitioners and researchers identify synergies and tensions, as some priorities are likely to be incommensurable, but many can be made more compatible through equitable engagement (cf. my website; podcasts, slides and reports in English, Spanish and German available as a thank-you to stakeholders).

My hope is that the model can help practitioners and researchers identify synergies and tensions, as some priorities are likely to be incommensurable, but many can be made more compatible through equitable engagement (cf. my website; podcasts, slides and reports in English, Spanish and German available as a thank-you to stakeholders).

More bad news emerging from my work: despite actors’ growing awareness, answers in the transformational spirit required by the challenges’ magnitude are mostly still in their infancy. In public-facing representations communicating to consumers initiatives’ meanings, stakeholders often forefront socio-economic and environmental objectives as the driver of their engagement. While purporting to ‘build bridges’ and playing into consumers’ desire to ‘help’, the charitable meanings created also paint initiatives as ‘nice-to-have’. This altruistic canvas hides from view the poor practices, incentivised by low prices and productivity-maximising pressures, which partly have brought about the current crisis. What is more, unbeknownst to consumers, initiatives can exacerbate the power asymmetries they purport to bridge between especially cocoa producers and chocolate companies. Through companies establishing certification schemes they oversee themselves and working directly with producers, they cut out intermediaries. While this approach can, much to growers’ delight, increase farm-gate prices, it also exacerbates corporate dominance and creates quasi-monopsonistic structures, leaving producers with few or no other sales outlets.

In my view, more equitable connections are crucial to tap into Southern stakeholders’ expertise through genuine participation and empowerment and transform the sector towards greater viability. While certification schemes such as Fairtrade or organic can offer part of the answer and reduce the likelihood of infractions vis-à-vis most uncertified chocolate, ever more stakeholders agree they have to move beyond. I would argue that supporting smaller-scale cocoa processing and chocolate production in the global South could help promote greater value capture at origin, more viable practices and broader genetic diversity– Nicaraguan chocolate proved a particular favourite for my focus-group and public-engagement participants. To build genuine consumer-producer bridges, conduct prioritising equity and fairness, towards humans and the environment, would indeed be a principle worth applying in cocoa, but also far beyond.

It is up to you what you make of all this good and bad news, whether you opt to order industrial volumes of your favourite chocolate, figure out how to shock-freeze chocolate and then buy a bigger freezer, or choose another route. It is up to consumers, with the limited power of their purse-strings, and chocolate stakeholders, with the virtually unlimited power of their production-network tentacles, to make the informed, transformational choices necessary to help ‘save our chocolate’: living incomes for Southern stakeholders, production practices which protect rather than destroy the environment, and interactions in a spirit of equity and fairness rather than charity.

However, in light of the crisis, I would advise you to take to heart two fundamental truths which have made my PhD – aka thinking about chocolate 24 hours a day, seven days a week for three years – infinitely more enjoyable:

– Chocolate is proof that God wants us to be happy.

– Chocolate comes from cocoa, which grows on a tree. That makes it a plant. Therefore, chocolate is practically salad. Eat up!

Watch | Duncan Green on how change happens (and how to make it happen)

On Tuesday, 17th May Oxfam’s Duncan Green spoke at the Global Development Institute on ‘How Change Happens (and how to make it happen)’

Embrace the PhD journey, get help, try your luck and it will get done!

By Judith Krauss, Post-doctoral Associate, Global Development Institute

We were privileged to welcome back to Manchester three of our own: as part of its annual postgraduate research conference, the School of Environment, Education and Development, home to the Global Development Institute (GDI) and the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Doctoral College, invited back three alumni to share thoughts and experiences on doing a PhD, but also managing the transition into post-PhD life.

Dr Beth Chitekwe-Biti, Founding Executive Director of Dialogue on Shelter, an NGO working in Zimbabwe and a contributor to the Slum/Shack Dwellers International network, and Dr Gemma Sou, a lecturer at GDI’s Manchester sister institute, the Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute, both completed their theses at the Institute for Development Policy and Management (now GDI). They were joined by Dr Lazaros Karaliotas, an alumnus of Human Geography at Manchester, who now works as a post-doctoral researcher in Geography at the University of Glasgow. All three alumni of the University of Manchester had a multitude of experiences to share with our current generation of PhD researchers, both from their PhD journeys and from life and work beyond the PhD.

Although all three stressed that they could not share any universal words of wisdom given the specificity of each PhD researcher’s own experience, a common theme was the importance of holding on to the idea that ‘the PhD will get done’. Taking time off from the PhD was thus a key recommendation to recharge batteries, maintain a balance and get a fresh perspective. Equally, especially in the most trying times, crucial advice was to get all the help necessary from diverse sources, and to get help early.

The progression towards completing a thesis is likely to come with some difficulties, be they isolation on fieldwork, challenges in transforming fieldwork data into PhD chapters, or managing one’s own ambitions and expectations in relation to what a PhD is. According to all three alumni, a crucial step is therefore realising that panicking is very unlikely to be productive: after all, the final objective is ‘only’ a PhD, which will not be perfect. Reading a full PhD thesis early on to understand the limits, and manageability, of a doctorate, and recognising that a PhD is unlikely to be the author’s masterpiece, is likely to help with that realisation. Once this insight had set in, the journey became much easier for all three panellists, with one key recommendation being not to fear, but to embrace the path, and trust in the knowledge that the PhD will get done.

In this optimistic spirit, all three alumni also encouraged a ‘try your luck’ attitude to applying for jobs and grants. As any ‘failure’ in those circumstances can be regarded as really an opportunity to progress and evolve further, they encouraged applying for research council and other grants which may include what one may consider unlikely prospects. These applications can facilitate engagement to build a life post-PhD, as pots of money will be available to organise seminars or conferences and grow through fellowships and public engagement activities. Equally, they offer an opportunity to stretch beyond the comfort zone of one’s own research and continue building on the work already completed in transitioning into the post-PhD world, having found one’s own voice and argument often towards the very end of the PhD journey.

A recurring thread was also the importance of relating PhD work to audiences outside of academia. Beth continues to be passionate about co-creating knowledge between urban communities and academia especially in the field of urban planning, a topic on which she works continually in collaboration with local universities in Zimbabwe and the Global Development Institute at Manchester. Gemma founded viva voce podcasts, an award-winning platform for social-science researchers to present their work in five-minute podcasts to the interested public, and also went back to her research site in Bolivia to feed back some of her findings to the communities she had collaborated with during her research.

The thirty attendees appreciated the opportunity to exchange with three individuals kindly sharing their own, very diverse journeys, whose multi-faceted insights nevertheless boiled down to four key points: embrace the journey, get help, try your luck, and the PhD will get done!

Brazil in political crisis: what’s going on and what might it mean for development?

With the world’s attention trained on Brazil ahead of the Rio 2016 Olympics, its political leaders have made a splash with the impeccable timing of a synchronized swimming team, but unfortunately one whose members proceed to fall out, try to drown each other, and then all fail their drugs tests anyway.

Firstly, what just happened? Here is a not-entirely-impartial synopsis.

On Thursday Brazil’s Congress voted to begin impeachment proceedings against President Dilma Rousseff, meaning she is suspended from office and unlikely to return, and the coalition led by her centre-left Workers’ Party (PT) has been supplanted by a new administration led by the ‘big tent’ party PMDB. Dilma is culpable for window-dressing government accounts to make public spending appear lower. Her suspension follows huge demonstrations mobilised under an ‘anti-corruption’ motif. So, a victory for people-power holding corrupt politicians to account, right?

Well, it’s not quite so simple. In the Brazilian context Dilma’s infraction was comparatively minor, and the grounds for impeachment are debatable. Moreover, there was no personal gain involved, the aim being to justify continued spending on social programmes (arguably somewhat electorally-motivated), and Dilma refused to strong-arm any corruption investigations, even given clear opportunities and the increasingly apparent fact that her adversaries would use the investigations to catalyse her downfall. Meanwhile, the politicians leading the ‘anti-corruption’ campaign themselves face considerably more serious and more personal corruption allegations.

New interim president Michel Temer (PMDB) theoretically faces impeachable charges relating to Petrobras kickbacks. Eduardo Cunha (PMDB), speaker of the lower house and chief architect of Dilma’s demise, is now suspended for alleged intimidation and perjury, and obstructing investigations launched following the revelation of his several secret Swiss bank accounts containing millions in bribes. (His replacement is also under investigation for bribe-taking.) Renan Calheiros (PMDB), the leader of the Senate, who oversaw the final impeachment vote, faces nine criminal corruption investigations. In fact, some 53% of Congress faces criminal investigations.

Nevertheless, it seems feasible that for Temer, Cunha, et al the process will now, as Brazilians say, ‘end in pizza’, i.e. with no real consequences. The pro-impeachment movement was inflamed and orchestrated by Brazil’s right-leaning and famously wilful media, and the predominantly white, middle class protests focussed almost entirely on Dilma and the PT, typically voicing dissatisfaction with the struggling economy and the redistributive and state-focussed trajectories of 2003-onwards PT government. Arguably the principle raison d’être of the movement has now been fulfilled.

To be clear, almost nobody in this scenario is Snow White. The PT’s reputation as a principled ideological party has been tainted by several corruption scandals. Equally, though, few are seriously pretending that righteous outrage at Dilma’s inventive accounting is really much more than a pretext for cutting short her administration for other reasons, such as policy disagreement and the spluttering economy. Whatever the shortcomings of the Rousseff government – and there were plenty – this looks rather like a soft coup mounted by a plutocratic media and political class that has decided it no longer has to accept the outcome of the 2014 election.

Secondly, then, what implications might this have for development processes?

On the face of it, anybody who likes their development in an egalitarian and pro-poor flavour should be deeply concerned. The rise of the PT as a party of government, first at local and then, in 2003, federal levels, has been associated with a huge expansion in social policy and anti-poverty programmes, significant reductions in poverty and inequality, and a wide-ranging experiment in more deeply and diversely participatory democracy. Early 2000s Brazil quickly ascended to inclusive development ‘success story’ status. (Although the PT can’t take sole political credit for this, and also was initially helped considerably by a commodities boom.)

Meanwhile, the impeachment protests have consistently voiced grievances over the PT’s penchant for redistribution and state action, and, inside government, impeachment has been driven by a coalition of power-brokers, rightist evangelical Christians, powerful agricultural interests, and even apologists for the military dictatorship of 1964-85. (During the surreal televised spectacle of hundreds of corruption-accused politicians voting for Dilma’s impeachment ‘in the name of truth’, ‘in God’s name’, etc., Jair Bolsonaro’s statement particularly stood out. The ultra-right Rio congressman dedicated his vote to Carlos Brilhante Ustra, the head of the unit that tortured Dilma Rousseff as an anti-dictatorship guerrilla; his son Eduardo dedicated his vote to “the military men of ’64”.)

This must be seen within the longer historical context of deep-seated inequalities stemming from the nature of the Portuguese colonial project, with its small class of exceptionally wealthy and powerful landowners (latifundistas) and the largest slave population in history. The resulting post-colonial society was deeply stratified along lines of race and class, with world-leading levels of inequality, a large and impoverished underclass, and wealth, land and power concentrated in a small elite.

Painstaking erosion of these structural dynamics began with the late 1980s redemocratisation process and the new constitution that emerged. The social rights enshrined there, and their practically effective institutionalisation post-‘88, were hard-won results of intrepid social movement activism and canny political deal-making. The period of increased progressive state action from 2003 consolidated these gains. Now there are genuine fears that, as per a Rio favelado, “they’re stealing the little we’ve achieved”. As if symbolically confirming the worst, within hours of the impeachment vote against Brazil’s first female president, Temer unveiled his new cabinet, containing a significant contingent from the influential rural landowner bloc, and comprising 100% white men, in a country where 51% are women and 53% black or mixed race.

As such, to the question ‘what will this mean for inclusive development in Brazil?’ the instinctive answer is: who knows, but it’s probably not good. However, it’s not necessarily so simple. The coming period of more conservative and economically neoliberal government will amount to a test of the strength of the institutionalisation of the progressive aspects of the constitution of ‘88, but probably, more fundamentally, of how structurally profound the changes of the past three decades have been.

Politically, an important innovation of redemocratised Brazil has been not just the substance of policy decisions, but the underlying redefinition of political space; how things are decided and who decides. Economically, a new working/lower middle class of previously impoverished Brazilians, revitalised labour unions, and a more progressive tax structure brings new dynamics. Socio-culturally, there is increased attention on dynamics of gender and race inequality. Policies such as the world-famous Bolsa Família conditional cash transfer programme continue to enjoy relatively broad support, and rolling back such initiatives could be prohibitively politically costly. Acting president Temer has already suggested as much. While the new finance minister is speaking a recognisably austerian language given the flatlining economy, it’s also possible that short-term pressure may be eased by a degree of recovering growth as investors react favourably to a more advertently pro-business administration. It is also unclear what will happen politically; the 2018 elections could, under exceptional circumstances, be brought forward, and it’s probably too early to say what the outcome might be. Longer term, though, the underlying tectonics of the process that installed the new interim regime suggests that Brazil’s progressive political forces have a fight on their hands, again.

Losing and Remaking Home: conflict and displacement in Colombia

Drawing on the personal narratives of 72 internally displaced people in Colombia, gathered between December 2013 and August 2014 for a PhD research project by Luis Eduardo Perez Murcia at the Global Development Institute, the below story describes how human rights abuses and displacement shape people’s ideas of home.

The selected narratives illustrate the experiences of losing home after conflict and displacement, the material and emotional impacts of living without a place called home, and the process of remaking home following conflict and displacement. Participants are quoted using pseudonyms.

Watch and Listen| Jennifer Bair on Global Value Chains, Market-Making and the Rise of Precarious Work

Dr Jennifer Bair, University of Colorado at Boulder, recently gave a keynote lecture as part of the Brown/Manchester Workshop on Global Production Networks and Social Upgrading: Labour and Beyond. The workshop, funded by the Watson Institute’s Brown International Advanced Research Institute Alumni Research Initiative as well as Manchester’s Global Development Institute, was hosted by our Global Production Networks, Trade and Labour research group.

>Watch a short introduction to her talk below or listen to the podcast in full.

Call for Abstracts – “Mobile Technology for Agricultural and Rural Development in the Global South” Workshop

A call for abstracts/presentations on ‘Mobile Technology for Agricultural and Rural Development in the Global South’. The workshop will be held on Wednesday, 20 October 2016. The deadline for abstracts is 31 July 2016.

In recent years, there has been growing activity around use of mobile technology and information systems for agricultural and rural development in the Global South. Numerous interventions have been demonstrated through widespread application of new technologies some of which have been scaled. Technological innovation in small-scale agricultural systems also creates demands for new forms of organization and institutional change, and there have been a number of impact studies of mobile technology-led agricultural service provision which have provided mixed and uncertain results.

Growth of research and policy analysis in this field has been slower than the pace of change for practitioners, and much remains to be done, particularly in bringing socio-technical views of information technology and agricultural development perspectives together.

The aim of the 20th Oct Workshop is to share research and practice on current trends in “mobile technology for agricultural and rural development in the Global South”: specifically to bring together researchers from diverse disciplines and practitioners with experience of implementing mobile applications and agriculture information systems in differing country contexts. We hope the workshop will shape a future research agenda and form the basis for future research and practitioner partnerships, as well as contributing to an edited book publication.

Research or practitioner papers (which can be submitted either before or after the workshop) will be peer reviewed, and selected for inclusion into an edited book. The book will target practitioner, policy and academic audiences.

Prospective presenters should submit an abstract of 200-400 words outlining their proposed paper or presentation to: mobileagworkshop@gmail.com with a deadline of 31 July 2016.

The following timeline will be observed:

- 31 July 2016 – prospective presenters to submit an abstract of 200-400 words outlining their proposed presentation/paper to: mobileagworkshop@gmail.com

- 14 August 2016 – presenters to be notified of response to abstract

- 17 October 2016 – draft papers (desirable but not essential) to be circulated to workshop participants

- 20 October 2016 – workshop for presentation and discussion of papers

If you have any queries prior to abstract submission, please contact Dr Richard Duncombe, Centre for Development Informatics, The University of Manchester.

CDI (the Centre for Development Informatics) is based at the Global Development Institute at the University of Manchester. GDI plays a major role in supporting the University’s commitment to addressing global inequality, and aims to create and share knowledge to inform and influence policy makers, organisations and corporations, so that they can make positive and sustainable changes for people living in poverty. The Institute builds on The University of Manchester’s world-leading reputation for Development Studies research, which was ranked 1st for impact and 2nd for quality in the UK Research Excellence Framework 2014, and third in the QS World University Rankings.

CABI (Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International) is an international not-for-profit organization that provides information and scientific expertise to solve problems in agriculture and the environment as part of a broader global development objective. CABI are a leading global publisher producing key scientific publications, including CAB Abstracts, Compendia, books, eBooks and full-text electronic resources. CABI also manage Plantwise a global programme, run by trained plant doctors, where farmers and extension workers can find practical plant health advice, getting specific information direct to extension workers and farmers in the field.

Are we geographers? Reflecting on the American Association of Geographers conference 2016

The Global Development Institute held a launch celebration overlooking the Golden Gate Bridge bringing together 45 geographers from 18 different universities. Photo: Kristen Shake

By Aarti Krishnan, PhD researcher

As 8000 geographers, and a smattering of development and politics scientists descended on the streets of San Francisco for the recent Annual American Association of Geographers (the crème de la crème of geography conferences), the air was filled with a sense of intellectual prosperity.

The Global Development Institute was there in full force. We organized 3 sessions, had over 7 presenters, and several staff members who were discussants on numerous panels and sessions (full details below). We presented work on a range of topics from beyond imperialism to inclusive urban cities, from conflict and displacement to remaking the global economy. I heard stories of struggle, inequality, climate vulnerability and conflict, which just reinforced the fact that we live in a fragile and terrifying world. To solve a problem, we must first try to understand it, so I sought to attempt to comprehend the contribution of geography to the broader development debate, especially the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SGDs, particularly to development specialists are so important because they aim to build a resilient world in the face of this fragility.

Many geographers feel excluded from the SDG process. Some state that the SDGs are not systematic and are essentially a cumulative sum of everything that development stakeholders wanted. A few also believe that many of the goals are discursive and thus may counteract each other leading to paradoxes. So in this scenario – how do different specialties within geography truly engage with development and what role can geographers play?

To answer these questions let me first point out that geography in and by itself encompasses a plethora of specialties including: animal, applied, business, climate, communication, cultural, political, development, disability, economic, energy, environment, ethics, ethnic, information systems, goods and agriculture, education disasters, health, historical, indigenous, polar, regional development, financial geographies – and so on! This goes to show how fluid geography is and how it has grown to become an inter and multi disciplinary subject itself. This has enabled many geographers to engage with the SDGs far more than one would have previously imagined.

Throughout my time at the AAG, I came to understand that geographers aren’t there to reinvent the SDGs. Re-inventing would mean creating new imaginary discursives for SDGs. Instead, geography seeks to comprehend the imaginary that already exists by making sense of complex global and local relations. The way it does this is by providing in-depth rich empirical substance that helps create more informed, progressive critical goals. It narrows and improves scope and legitimizes the work done by grassroots practitioners. Hence, geographers help with the little things, the everyday stories that span several specialities which cumulatively add up to building resilience at macro scales.

My experience has helped me realize that a sense of ‘place’ pervades various specialties of geography. The fact that territoriality provides identity, moving beyond physical borders to shape and reshape communities and countries. It permeates the very meaning of who we are, where we come from and possibility where we go from here. It is then our duty as academics (critical thinkers or radical idealists) to seek to truly understand and make more sustainable this ‘place’ – be it this world, country, community or a person.

I, along with many of my colleagues at GDI have often thought of ourselves as development specialists. However, after my time at the AAG, I ask myself, does development fit into the remit of geography or does geography fit into development? I can no longer draw a clear cut distinction between the two disciplines. So to answer whether we are geographers? The conclusion I have drawn is that there is a little bit of a geographer in all of us!!

Aarti Krishnan won the Economic Geography Specialty Group Best Student Paper award for “Expansion of regional value chains: The case of Kenyan horticulture”, which demonstrates how regional value chains evolve into global value chains in the marketing of agricultural produce.

Global Development Institute presenters:

Uma Kothari: ‘Transnational networks of resistance: contesting colonial rule and the politics of exile’ in a session-titled: Beyond Internationalism II: More-than-national thinking at the twilight of Empire (1850-1950). She also was a discussant for a session on Theorising development in turbulent times and chaired a session on Celbritized aid and advocacy encounters.

Diana Mitlin: ‘Understanding inclusive cities: insights from India’ in a session on Urbanization in South and Southeast Asia.

Luis Perez: ‘Losing Home following Conflict and Displacement’ in a session called Home: Life on the Margins of Home III: Mobility and Belonging.

Matthew Alford: ‘Public and private governance in South African fruit global production networks: complementary, but who benefits?’

Rory Horner: ‘Upgrading within South-South production networks: health and economic dimensions in South Africa’s pharmaceuticals’.

Rachel Alexander: ‘Governance for Sustainability in Global Production Networks: Exploring the Case of UK Retailers Sourcing Cotton Garments from India’.

Aarti Krishnan: ‘What’s the point of environmental upgrading? Comparing Kenyan horticultural farmers supplying different end markets’. She also organised (along with Stefano Ponte from Copenhagen Business School) three sessions within the Remaking the global economy stream with a sub-theme of Global Production Networks and the Environment.

300 economists call for tax haven crack down

Global Development Institute Professors David Hulme and Kunal Sen have joined with 300 other top economists, calling on world leaders to “lift the veil of secrecy” surrounding tax havens.

The letter, reproduced in full below, comes ahead of a global Anti-Corruption summit, which will be chaired by David Cameron on Thursday. Thomas Piketty, Angus Deaton, Ha-Joon Chang and Jeffry Sachs are fellow signatories and it has been covered by the BBC, Guardian, FT and Telegraph among others.

In a forthcoming book entitled ‘Should Rich Nations Help the Poor?’, David Hulme highlights that:

“A vast and well-paid network of lawyers, accountants and financiers based in offshore tax havens support multinational companies in profit-shifting and wealthy people in hiding their ownership of companies.”

To assist lower income countries in their efforts to generate domestic tax revenues, Hulme argues that rich nations should do much more to stamp out tax avoidance and evasion through changes to international rules and a step change in tax transparency.

Following revelations within the Panama Papers, including the financial resources being sucked out of many African countries, we hope the Anti-Corruption summit this week inject new momentum towards the creation of a more equitable global tax system.

Dear world leaders,

We urge you to use this month’s anti-corruption summit in London to make significant moves towards ending the era of tax havens.

The existence of tax havens does not add to overall global wealth or well-being; they serve no useful economic purpose. Whilst these jurisdictions undoubtedly benefit some rich individuals and multinational corporations, this benefit is at the expense of others, and they therefore serve to increase inequality.

As the Panama Papers and other recent exposés have revealed, the secrecy provided by tax havens fuels corruption and undermines countries’ ability to collect their fair share of taxes. While all countries are hit by tax dodging, poor countries are proportionately the biggest losers, missing out on at least $170bn of taxes annually as a result.

As economists, we have very different views on the desirable levels of taxation, be they direct or indirect, personal or corporate. But we are agreed that territories allowing assets to be hidden in shell companies or which encourage profits to be booked by companies that do no business there, are distorting the working of the global economy. By hiding illicit activities and allowing rich individuals and multinational corporations to operate by different rules, they also threaten the rule of law that is a vital ingredient for economic success.

To lift the veil of secrecy surrounding tax havens we need new global agreements on issues such as public country by country reporting, including for tax havens. Governments must also put their own houses in order by ensuring that all the territories, for which they are responsible, make publicly available information about the real “beneficial” owners of company and trusts. The UK, as host for this summit and as a country that has sovereignty over around a third of the world’s tax havens, is uniquely placed to take a lead.

Taking on the tax havens will not be easy; there are powerful vested interests that benefit from the status quo. But it was Adam Smith who said that the rich “should contribute to the public expense, not only in proportion to their revenue, but something more than in that proportion.” There is no economic justification for allowing the continuation of tax havens which turn that statement on its head.

Seeing from the South: an international exchange with South African shelter activists

By Dan Silver, Diana Mitlin and Sophie King

“We are poor, but we are not hopeless. We know what we are doing”.

This is Alinah Mofokeng, one of three activists from the South African alliance of community organizations and support NGOs affiliated to Shack / Slum Dwellers International (SDI) who came to visit Manchester last month. The three came to explain their approaches and to exchange knowledge with local organisations through a combination of visits around Manchester and Salford, and a half-day workshop drawing together activists from around the country.

While South Africa and the UK might initially appear to be worlds apart, previous discussions between low-income communities in the global North and South had identified commonalities in their disadvantage. Potentially there are approaches that can be drawn upon and adapted in order to resist marginalisation and improve local communities, which can work across different places and contexts. This was the basis for Sophie King (UPRISE Research Fellow) and Professor Diana Mitlin (Global Development Institute, University of Manchester) inviting the South African Alliance to meet with UK community groups in March, drawing on a long history of community exchanges. This coincided with the Alliance participating in the Global Development Institute’s teaching programme with community leaders lecturing on their experiences and methods.

Alinah Mofokeng (Federation of the Urban and Rural Poor), Nkokheli Ncambele (Informal Settlements Network) and Charlton Ziervogel (CORC) all talked about their experiences of being part of the South African Alliance of SDI. This alliance has pioneered people-centered development initiatives by and of people in poverty since 1991. Their foundations are established in the grassroots, working on issues that emerge from the daily experiences of poverty, landlessness, and homelessness to bring immediate improvements and long-term inclusive citizenship within cities.

SDI’s approach to organizing is grounded in women’s led savings schemes, in which each member saves small amounts and does so with the support of their own collective savings group, so they are able to improve their own lives, and that of the wider community also. Solidarity is central to their approach and savings schemes are encouraged to federate to have stronger influence on city and state government. In the process of coming together they learn about their respective needs and challenges and respond collectively. If one member’s family does not have enough to eat, the group may decide that week’s savings will be spent on putting bread on their table. Once one savings scheme is formed, they share their learning with other marginalised people around them and support others to form schemes of their own that can join the network.

This extends beyond initial collectives to direct community-to-community learning exchange at city, national, and international levels. From here, they are able to show that they are together and are capable, which means they can influence the government from a more powerful basis – as Nkokheli said, they have been able to say to the politicians: “you are eating our money and not doing what we want. We say, enough is enough!” Nkokheli said that once the community shows that they are capable, for example through building their own toilets in the informal settlements and developing savings, politicians are more likely to listen.

This extends beyond initial collectives to direct community-to-community learning exchange at city, national, and international levels. From here, they are able to show that they are together and are capable, which means they can influence the government from a more powerful basis – as Nkokheli said, they have been able to say to the politicians: “you are eating our money and not doing what we want. We say, enough is enough!” Nkokheli said that once the community shows that they are capable, for example through building their own toilets in the informal settlements and developing savings, politicians are more likely to listen.

The exchange of different ways of doing things between the South African Alliance and UK organisations certainly had an impact – showing us that the exchange of ideas about solidarity, a self-reliant ethos, and having a long-term vision for more inclusive cities is powerful enough to make sense across continents. One of the participants in the meeting was Ann from a group called Five Mummies Make, which is a self-help group in Scotland who have come together to sell handmade crafts, put on events and contribute to local charities; through meeting every week, the women have improved their own well-being in the process.

After the workshop, Ann was inspired to make a bigger difference than they were already achieving, saying that:

“If we bring together a bigger group, a federation, we can make such a bigger difference within the community, so not just small differences for individuals…I want to go back now and make the changes in the community, without having to go cap in hand asking for help constantly, but saying – this is what we want…”

Alinah, Nkokheli, and Charlton visited the United Estates of Wythenshawe for an extended lunch to meet people involved in Mums’ Mart. Mums’ Mart was started by a group of parents who came together after speaking to each other in the playground at their children’s school in Wythenshawe. Through chatting, they realised that they shared experiences of feeling isolated, and that their kids weren’t getting to take part in everyday activities. To address these problems the mums now meet every other week to have a meal while their children play, and they organise ‘market days’ to bring people from the estate together and raise money to take their families away somewhere fun for a day or a week.

After the exchange, members of Mum’s Mart have begun to emulate the SDI savings model and are holding weekly savings meetings, alongside their income-generating activities and monthly committee meetings to review progress; they also have ambitions about how over the long-term they can bring practical social change beyond their immediate group. Sharon Davies, the group’s treasurer, told us that since the visit Mums’ Mart have set up their own savings scheme and it is going well, and that they “have loads of really good ideas as to where we are going to go with Mums’ Mart from now on”.

This was certainly not just a one-way street of learning from the SDI approach. Nkokheli, who was initially surprised that poverty existed in the UK after visiting a homeless group in Manchester, told us that: “The exchanges are very important to us, because it mobilises the community…and also [helps] to train communities to do things, [to see] what other people are doing for themselves. Here in Manchester, I learnt a lot…The systems are not the same, but the look of things are the same – there are things we can learn from Manchester, and there are things Manchester can learn from us”.

This was certainly not just a one-way street of learning from the SDI approach. Nkokheli, who was initially surprised that poverty existed in the UK after visiting a homeless group in Manchester, told us that: “The exchanges are very important to us, because it mobilises the community…and also [helps] to train communities to do things, [to see] what other people are doing for themselves. Here in Manchester, I learnt a lot…The systems are not the same, but the look of things are the same – there are things we can learn from Manchester, and there are things Manchester can learn from us”.

Through this exchange then, there have been concrete changes that have already taken place. It also shows the value of bringing together groups who might be marginalised from politics and from economic opportunities, to share ideas, tactics and strategies. There is most certainly scope in the UK to build on the approach that SDI take: developing a more self-reliant social action approach; coming together, initially in close supportive relationships between neighbours, but with a view to wider solidarity across groups and between areas; and showing the government through practical activities the capabilities of people living in low-income areas and the direction that poverty reduction strategies should take.

As Alinah said, “we are not hopeless. We know what we are doing”.